In these days of increased intelligence powers, a ballooning national security budget, a giant new ASIO headquarters in Canberra, and endless discussions about WikiLeaks and the right to know, I wanted to look at the effects of spying on those who have been its targets. David McKnight and others have written extensively about our spy agencies. This book is the stories of those spied upon. There is particular satisfaction in the fact that a group of Australians who have had their lives secretly recorded in detail over many decades are at last getting their own back. We are finally writing about them instead of them writing about us.

In compiling this book I approached almost a hundred people who I thought were likely to have been ASIO targets, and gave them instructions about how to apply for their files. About half were told they did not have files. In some cases this was simply not believable. Nadia Wheatley was told she did not have a file although her arrest record was similar to mine and she was heavily involved in the targeted areas of Aboriginal rights and anti-Vietnam war activity.

Not everyone was keen to see their files. My sister Verity, a historian and one-time Trotskyite, did not want to look at hers in case she found out that someone she knew and liked was an informant. Academic Ann Curthoys was so reluctant to look at hers that in the end she declined to participate. I found myself strangely unable to open my own large parcel for many months. Some were reduced to tears. The writer Roger Milliss wept as he read about the extensive surveillance his father had endured; including twenty pages of intrusive details about his father’s funeral.

During this process I became a bit of an expert on who seemed to attract files and who did not. Being in the Communist Party or a Trotskyist group was an obvious qualification, but some CPA members, strangely, did not have files. Being arrested could trigger a file, but not necessarily. Being involved, however marginally, with Eastern European countries almost always aroused interest, as did having progressive views and being involved with communications systems or scientific research. Any combination of these factors was a likely trigger.

What we discover may well be regarded as ancient history, but it should shine a light on the nature of our secret police. Can a leopard really change its spots? Given ASIO’s long history of incompetence, can we really trust it to protect us today? At a time of considerable expansion of its resources and powers, do we simply ignore the history and cross our fingers about the future? When does dissent become subversion and when is spying on citizens the legitimate role of government?

The young students, Christians, mothers, and unionists of the anti-Vietnam movement, land rights campaigns, gay rights action and so on, were never a danger to the government. We should have been dealt with as a public order issue, not as a threat to the state. On the evidence of this book, ASIO has not shown that it is capable of making that distrinction.

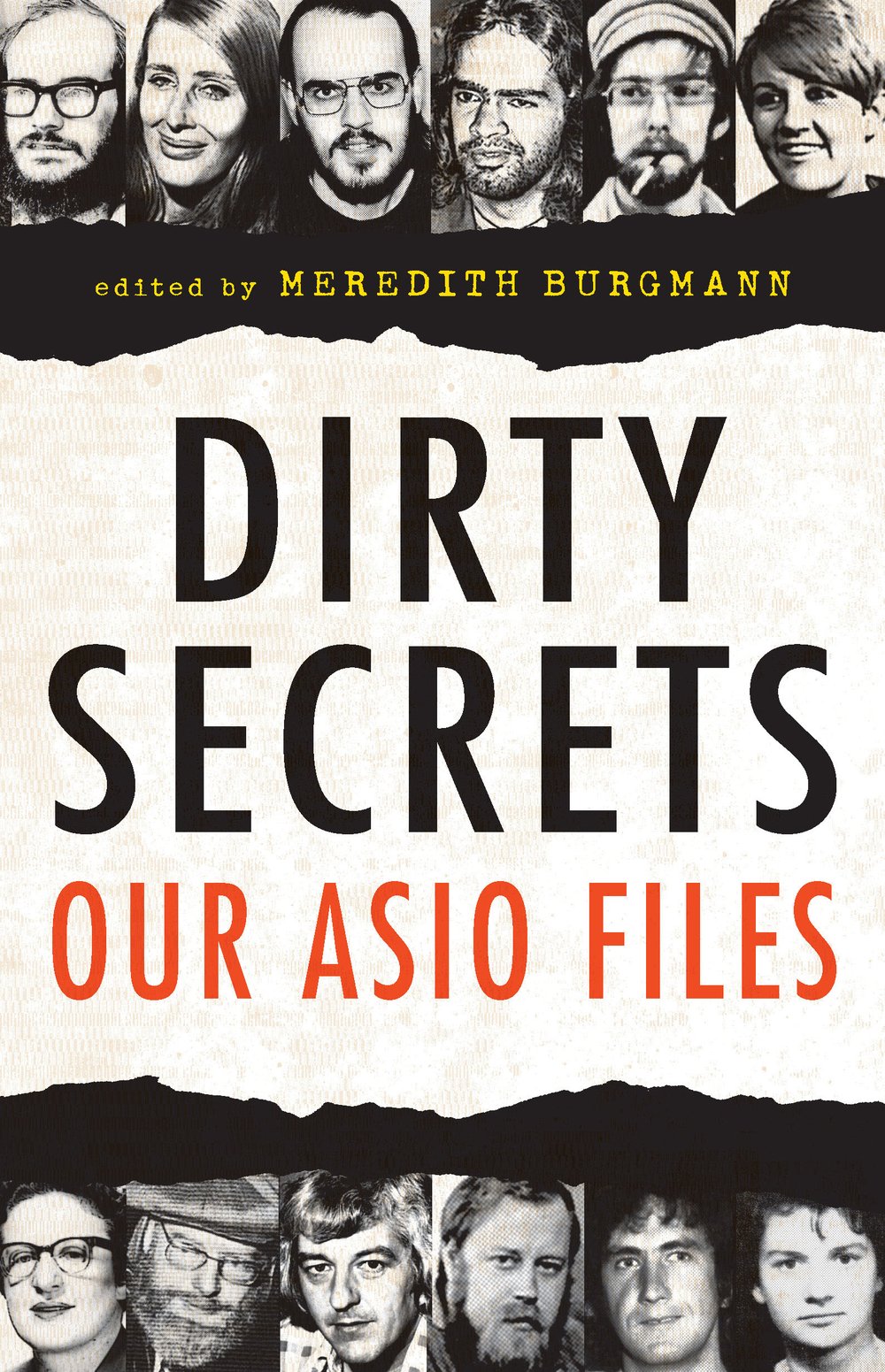

This is an edited excerpt from the Introduction to Dirty Secrets edited by Meredith Burgmann, out now from NewSouth.