In contemporary bilateral relations, great emphasis has been placed on India and Australia’s historical connection with the Commonwealth. The stress laid on a shared past is deeply misleading, however, for each colony was tied to Britain in the early twentieth century under very different conditions. Both, it is true, strained against the imperial embrace, but the respective forms of colonisation, collaboration with, and resistance against the empire diverge widely. At the beginning of the twentieth century, each colony pulled in a different direction. As a settler society geographically isolated from Britain, newly self-governing and freshly assertive, in 1901 Australia adopted the White Australia policy, effectively preventing the further migration of nonwhite settlers. This, much to Britain’s frustration, included those from British India, undermining an attempt to project a sense of unity within the empire. Prior to 1901, however, a substantial population of Indians had come to Australia and were granted limited rights of residency. British India, White Australia charts the lives of some of these settlers, charting a social history of their struggles against Australian legislation, which prevented them from voting and working in many industries.

As a political history, British India, White Australia demonstrates the extent to which Australia’s ties to Britain constrained its relations with India in the twentieth century. In the early twentieth century, there were strong impulses in Australia to take part in the colonial project: an avid consumption of imperial culture, and a largely uncritical assumption of British attitudes about imperialism, to the extent of lobbying for Australian boys to be able to enter the Indian Civil Services. Meanwhile in India, nationalists across a number of movements and deploying a range of ideologies were struggling to problematise and moderate the same imperial project. The discrimination against Indians in the so called ‘white dominions’ only served to further escalate Indian anticolonial movements. One of the reasons that the Indian National Congress swapped its aim of Dominion Status for complete independence in 1929, for example, lay in Jawaharlal Nehru’s observations that dominionhood was inextricably linked to whiteness.

In early twentieth century Australia, support for Indian independence movements, and in particular Gandhi, were seen as a form of disloyalty to the empire. This began to show signs of eroding after the Great War, following enhanced people-to-people contact between Australians and Indians, following imperial culture and propaganda that emphasised Indian contributions to the war effort, but also wartime cooperation at the western front and in the Middle East; of Australians travelling to India and upon their return, writing critically about imperial conditions; and the impact of Indian delegations travelling to Australia to plea for changes in discriminative legislation, began to create openings for a more receptive audience in Australia. The work of disparate actors – from the Theosophical Society to the writers from the Australian left, and of individuals from C.F. Andrews and Annie Besant to Srinivasa Sastri and Indian students studying at universities in Sydney and Melbourne – led to a discernible shift towards a more sympathetic understanding of, and in some quarters, a willingness to support, Indian nationalist movements.

The independent formation of Australia-India Associations by notables – academics, ministers, and mayors – in three states across Australia in 1943, in part to mobilise for famine relief, were an important reflection of a need to engage with an independent India after the war. This coincided with the opening of High Commissions in Canberra and New Delhi in 1943 and 1944, providing a mechanism for direct communication and initiatives to foster greater understanding, enhance cultural and educational exchanges. In the atmosphere of the Second World War, however, Britain continued to intervene, for example preventing a delegation of Indian journalists from visiting Australia in 1944 and failing to provide shipping for Australian wheat to ameliorate the Bengal famine. And yet as decolonisation loomed, there remained a resistance among Australian governments to criticise the record of the Raj in India.

Australia’s attempts to establish bilateral relations with India after its independence have been extensively analysed by scholars who have explained the historically weak relationship as an outcome of alignments in the Cold War. Many note that Australian attempts to engage with India have gone unrequited; few have tried to appreciate why this might be the case. At least one element of this has to be that Australians have brought to the table a presumption of Commonwealth synergies which simply do not align with Indian experiences. Australian identification with a reified British empire continued to colour its external relations with India after 1947.

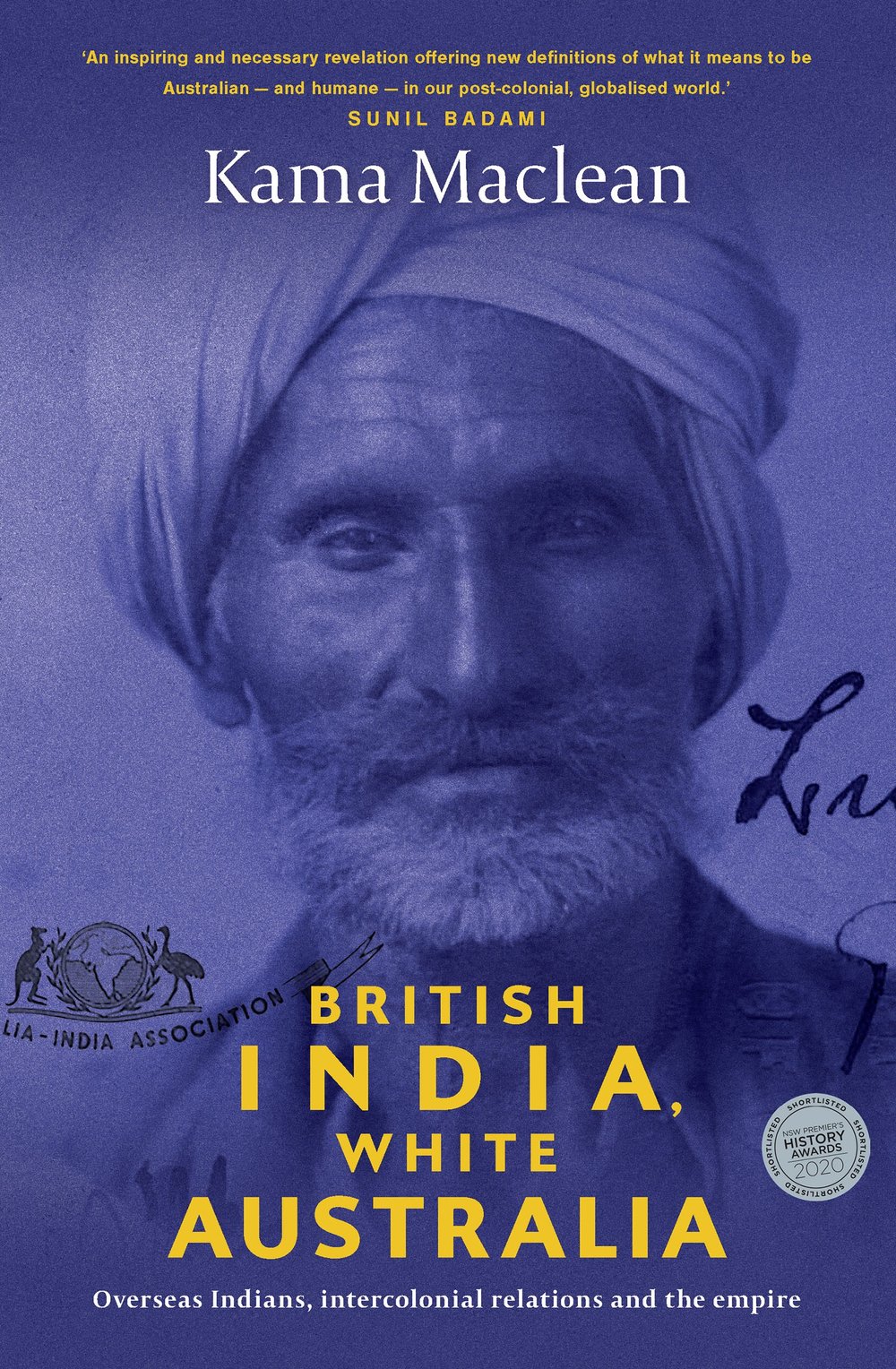

Kama Maclean's book British India, White Australia: Overseas Indians, intercolonial relations and the Empire will be published by UNSW Press is March 2020.