When in 2005 Parragirl Bonney Djuric climbed on top of some rubbish bins and jumped the fence into the yard of Parramatta Girls Home, she remembered ‘Peering up at its imposing façade … a place where at the age of fifteen I had spent eight months as a resident’. With her video camera in hand, Bonney found a way into the main building and down into the basement where the ‘dungeon’ solitary cell used to be. And although she was terrified of being caught, she was determined to ‘capture as much of what remained as possible’. The reason was simple, she said: ‘I needed answers. I needed to make sense of something that never made sense. To reclaim something of myself that had been taken from me in this place.’ Bonney Djuric is Parragirls support group co-founder and director of Parragirls Memory Project, and in these words as she recounts returning the site after many decades, to what was then the Norma Parker women’s detention centre, and literally having to break into the girls home to get ‘answers’ to questions that both the public and successive governments had denied or swept aside both over a century of operations and ever since its closure in 1974. This was not only an act of defiance but remarkably also a work of art. At the time an Honours student at Sydney’s National School of Art, Bonney was filming the site for a five-part animated film titled Asylum that she would complete that year.

Today, the name Parramatta Girls Home is only known to most Australians because of its exposure in the media as a ‘notorious’ place and, following a series of major judicial and state inquiries from 2001, as the location of unjustifiable violence meted out to children in care. National attention on these injustices culminated in the Royal Commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse, opening a chapter in the Australian narrative that remains difficult to reconcile. Despite these revelations, the story of the artistic transformation of the site through Parragirls’ art and memory has not been told. In the years since 2006 – when Bonney founded the Parragirls support group with Lynette Aitken and Wiradjuri woman Christina Green – creativity had become a crucial way to represent their experiences, particularly because they had no support network of any kind. Most Parramatta Girls had kept what happened a secret, buried deep under trauma and shame. And yet, in isolation, many former residents started writing stories, songs and poems. Others were painting, drawing or making all kinds of craft, such as latch hook, quilt-making and all kinds of needle work.

It was Bonney Djuric who instigated our first encounter in November 2011. Twelve months later, we formed the Parragirls Memory Project, which brought former residents of Parramatta Girls Home together at the girls home site to continue their work to confront and attempt to reconcile with the abuse they had suffered there, sometimes more than forty years after they had left as teenagers. By 2013, thanks to state and federal arts funding Parragirls Memory Project occupied a small corner of the site. And just in time, given that many of the women were providing testimony for the royal commission. They did so at great cost; not for personal benefit, because the formal and comprehensive nature of a royal commission is not about individuals … Parragirls had to work out for themselves how to tell their own story. This is why they returned to campaign to save the home as a living memorial and how their creative work began; how they came to embark on as a form of concrete restorative justice through art and memory at the site itself, working in tandem with First Nations artists and the traditional owners, the Burramattagal people of the Darug Nation.

Parragirls is the first publication of its kind to use images and the creative writing of former institutional occupants to open up the difficult spaces of Australian child welfare legacies. And the work of these women offers a unique emotional bridge for those who have followed the royal commission and who seek to comprehend the experiences of children in care. It demonstrates the power of art to generate new ways of engaging with injustice, not only to survive its consequences but also to imagine its legacies as an opportunity for change, to stand up and speak out, despite the ‘moral’ risks and the pain of doing so, as Bonney Djuric does here in her poem from 2008, ‘Number 123’:

They brought me here in a big black van

drove me into a holding pen

stripped off my clothing, took my name

and numbered me one two three

Exposed to moral danger they said

outside she’s at risk, be better off dead

not right in the head, gone astray, been misled

…

Unheard things are being spoken

silences are being broken

You can have the number one two three

My name belongs to me.

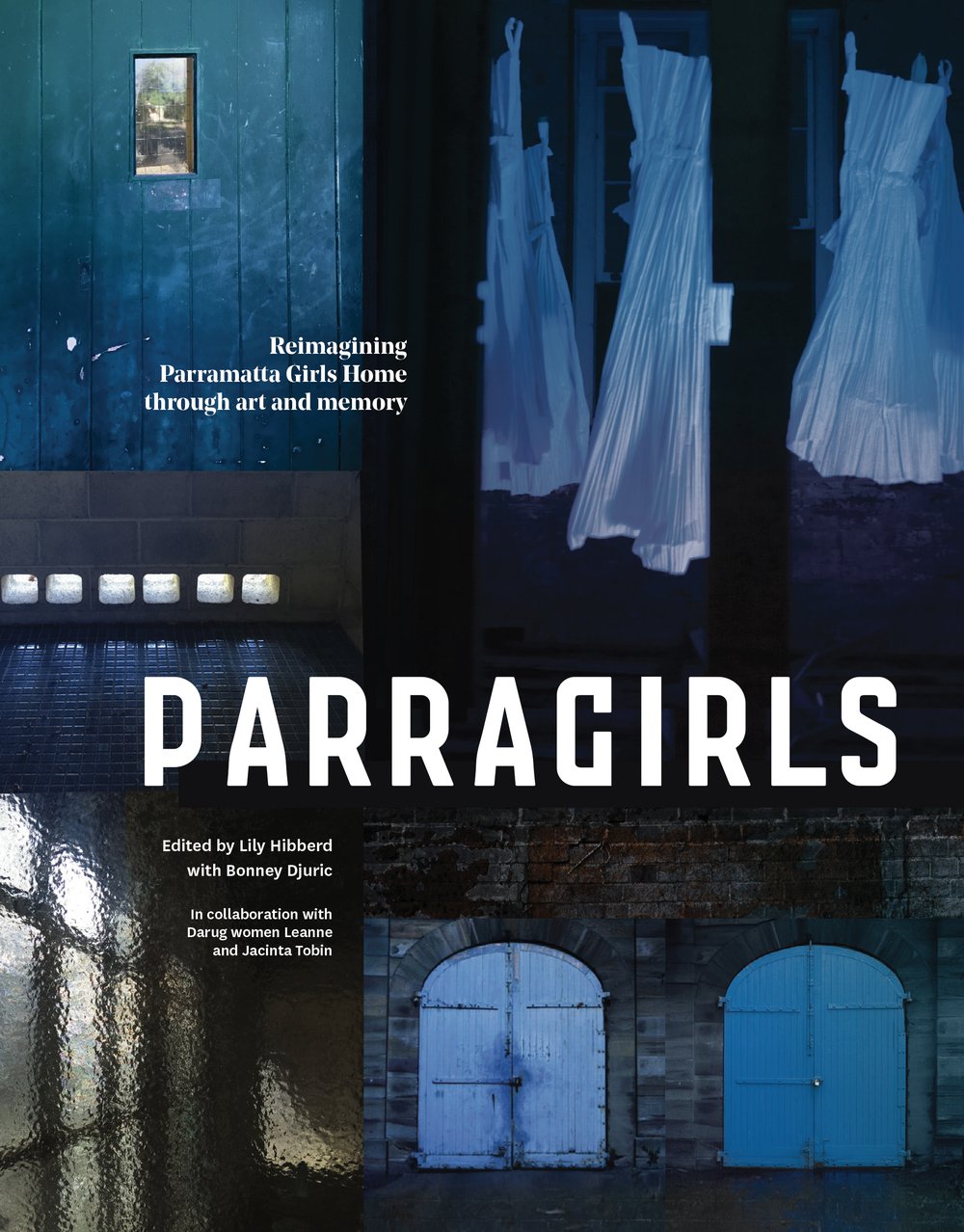

Lily Hibberd's and Bonney Djuric's book Parragirls: Reimagining Parramatta Girls Home through art and memory will be published by NewSouth in September 2019.