Whenever I tell someone I’m writing about madness they often nod agreeably – and then double-take. Did you say ‘madness’? I quickly fill the silence, which I assume comes from confusion and not disinterest, with my elevator pitch: my book, Bedlam at Botany Bay, is a history of madness in the early phase of colonial Australia, a study of disorder and breakdown in a society very concerned with order and improvement. If colonisation made individual lives into projects, they were filled not only with striving and material success, but with crisis and failure. As imperial officers, colonial doctors, venture colonists, and even exiled convicts built homes and businesses and worked for survival, promotion, or redemption, they came face to face with human frailty. In their more reflective moments, it reminded them how far they were from home.

As I speak I tend to see a question forming. How did you come to write about this? I appreciate its historical character, the way it assumes that our professional lives are not necessarily strategic – that we chance upon our paths, only later learning the right questions to ask.

This happened with madness and me. My partner, Stephanie, had arranged an evening for us walking through those sandstone Sydney streets which recall the colonial period – then lit by the vivid colours of ‘Macquarie Visions’, a bicentenary celebration of the achievements of Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie. Governor Macquarie has long been looked on as a visionary, an early believer in the potential of settler Australia, and his wife is beginning to enjoy some of the limelight. Projected onto the wall of the Mint, I think, or Hyde Park Barracks, was a list of social institutions the Macquaries helped to establish. One jumped out: a lunatic asylum, at Castle Hill. It was a jarring image. What did it mean to open a site of therapy in a colony of exile and punishment?

I have since learned almost as much as there is to learn about this hastily renovated stone building. I have thought and written about what it was and was not. Its creation suggested that Macquarie, a Scotsman, was influenced by his compatriots in the Scottish Enlightenment, who had great faith in the power of social institutions to address social problems. But this asylum was not particularly therapeutic. It was placed in the care of an amateur botanist and a string of disgruntled convict doctors, and chronically under-resourced. As the building literally fell apart around them, we might wonder whether the asylum residents felt abandoned – by reason, family, country, god. Or did they feel liberated? From the flogging post, the penal island, the gallows, and the rules and expectations of clerks, masters and magistrates. At Coal River, in present-day Newcastle, two bushrangers were caught plotting to stab a fellow prisoner so that one, who had already been at the asylum, could be sent back there and the other could enjoy a few weeks in Sydney as a witness. For them the asylum represented freedom. Doctors, commandants and judges figured as much, and grew suspicious of illness in general, and madness in particular, which was thought easier to feign.

Still, the notion of therapy and peace hovered over the asylum at Castle Hill. It also suffused the colony as a whole, as least in Macquarie’s imagination. He thought of it, in quiet moments, as ‘an asylum or penitentiary on a grand scale’ which might heal and restore those the wretched of the Empire.

It was also a place of terror. Macquarie’s image has been somewhat tarnished, in recent years, by revelations of his having sent soldiers into the country to terrorise local Aboriginal communities. And in the final years of his administration, a Commissioner of Inquiry was sent from London to conduct a thorough review of the colony, and show how it could be made into a beacon of terror so intense that it would deter men and women on the other side of the planet from committing crime. Macquarie’s successors implemented this program and saw this fear percolate through the community; some saw its fruit in madness and suicide. In a society so singular as New South Wales, asylums and hospitals were sites of contradiction.

More often than not, as I tell these stories of madness, there is a follow-up: but what do you mean, were they manic? Schizophrenic? Did all convicts have PTSD? Depression? Mental illness is embedded in place and time, and in this place and time, diagnoses were abrupt, pragmatic, informal. Bedlam at Botany Bay is not about diagnoses of illness so much as it is about responses to madness – a phenomenon which swells around mental symptoms and surfaces in jurisprudence, architecture, religion, art, literature and all levels of government. In the modern period it has gathered around the asylum and the psychiatric hospital, been rolled into miracle drugs, plunged into the Freudian subconscious and up to the nuclear and neurotic family, and higher, to epidemics of anxiety and depression. Here the past lies uncomfortably close to the surface; madness wears its history on its sleeve. Our current approaches are not the only approaches, and they are intimately related to broader and deeper social contours. Tracing the history of madness brings those contours into relief and shows us our past, and ourselves, in new ways.

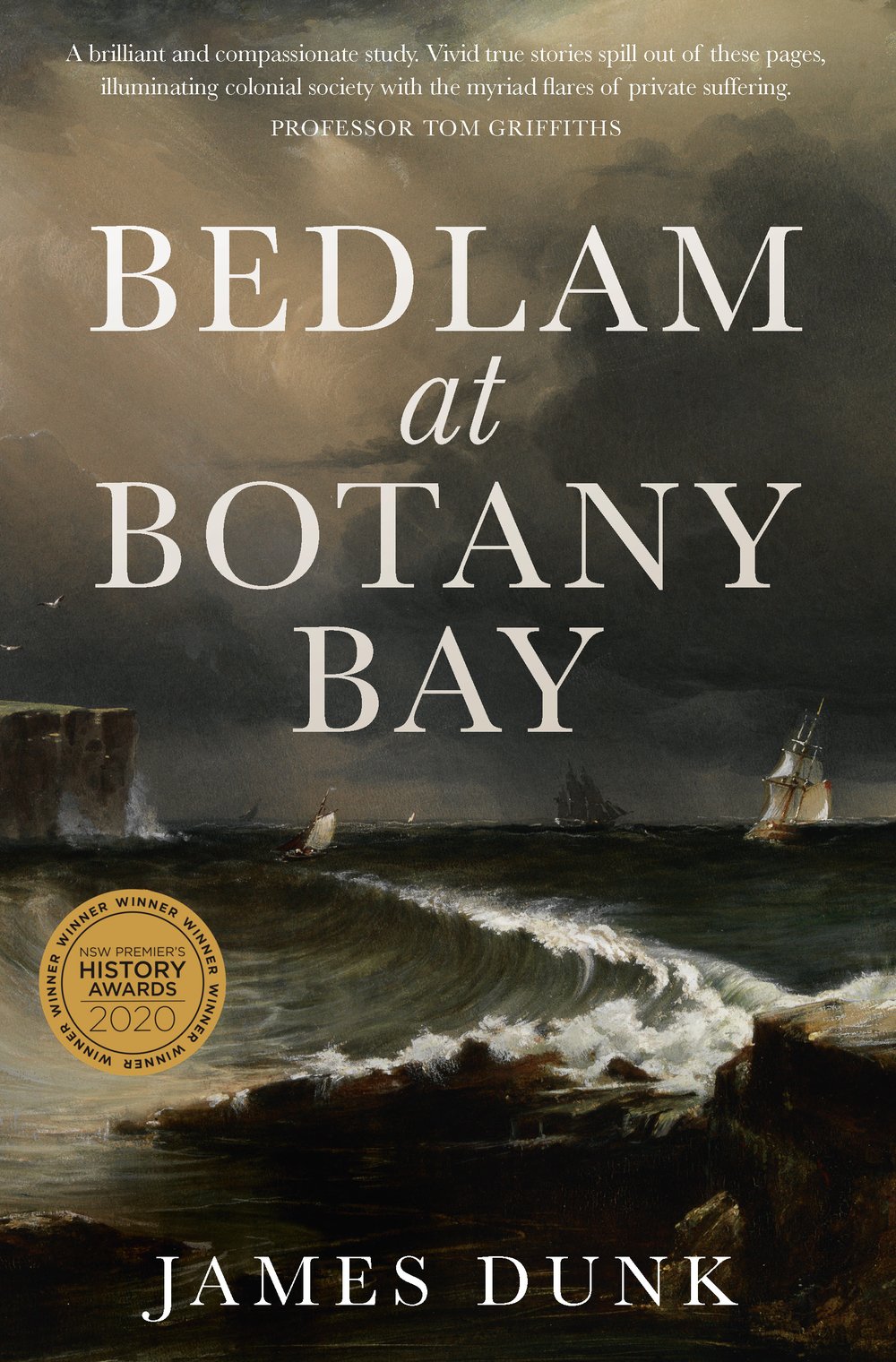

James Dunk's book Bedlam at Botany Bay will be published by NewSouth in June 2019.