When my mother told me that the first question that my father asked her when they met in her village on the Indian border was whether she knew the name of a famous economist, I thought she was having me on. When I learnt the next question he asked was ‘What’s seven times eight?’, I realised she was not. My father loves mathematics.

As Milan Kundera wrote, writing a memoir is a struggle between memory and forgetting. I think Kundera might have said it about matters more important, such as the battle of man against power, but it could apply to memoir writing just as well. Memory is a strange beast and the margin between memory, second-hand anecdote and journalism often begins to fade in the writing process.

As a psychiatrist, I often deal with disordered memory, from its manifestations as the negative lens that all memories are filtered through in depression, the prison of a traumatic memory in post-traumatic stress, to the slow fading of memory that precedes the entire loss of self in dementia.

To trigger more vivid memories in the hope of enabling richer writing, I often visited locations of my past: walking around the playground in my old high school before being accosted by security; and touring the grounds of the now shut-down Rozelle hospital, which was the old psychiatric asylum where I began my training as a psychiatrist and where I ended up giving shock treatment. I also looked at old photos and discussed family events with relatives.

Writing about childhood memories, especially those from Bangladesh when I was barely four or five years old, was particularly difficult. In writing these aspects of the book, and obviously the sections where I was outlining my parents’ memories of the Bangladeshi independence war and their courtship in and around it, the writing is as much journalism as it is memoir.

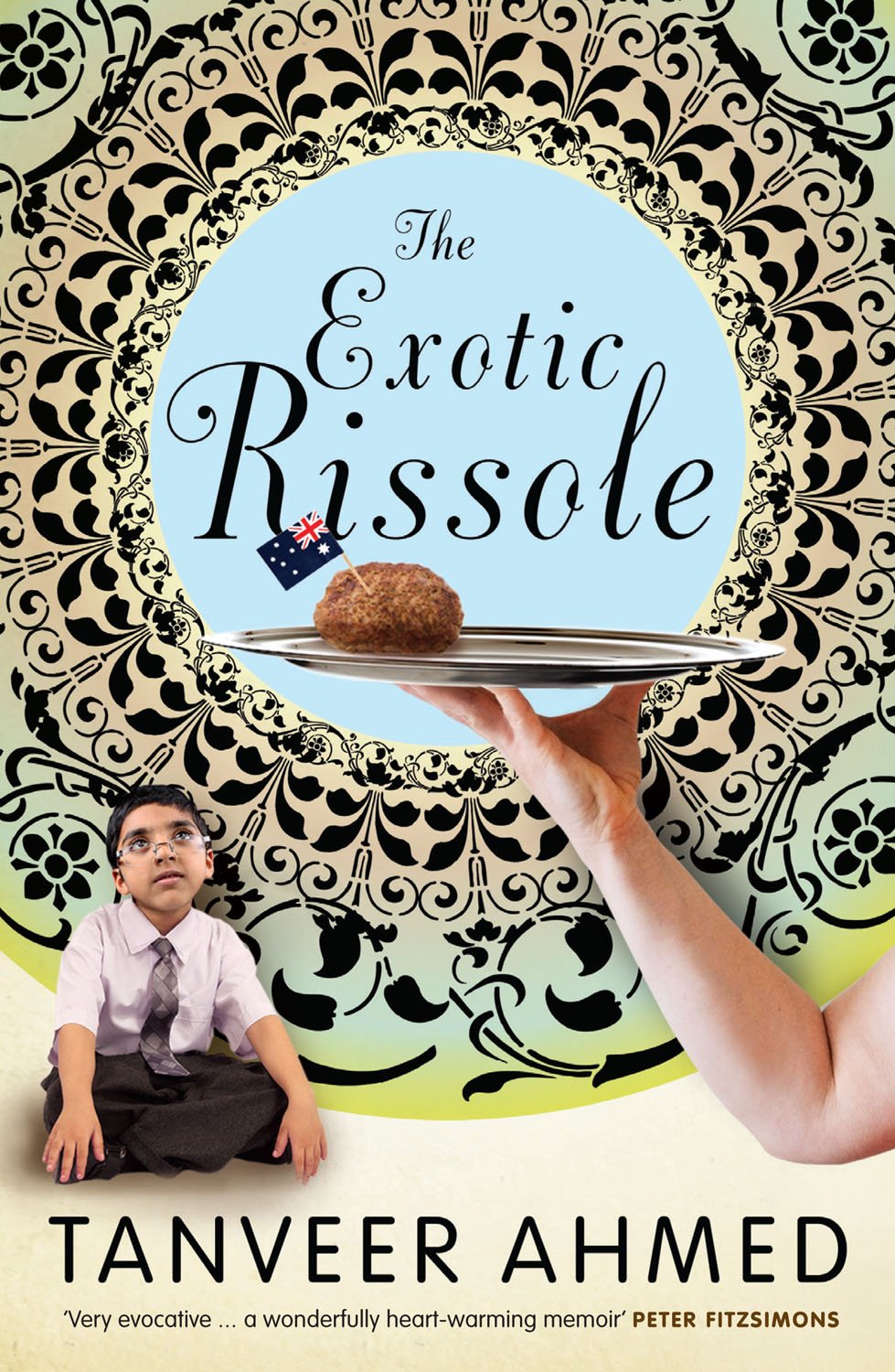

The book also led to a re-union with the childhood friend, Daryl, whose mother provided me with the rissoles. This was special, for there is something unique about childhood friendships. We knew the essence of each other, in spite of two and a half decades without contact, although I never would have foreseen him becoming a pastry chef.

There is also the challenge of what to include and what to leave out. The genre works best when the writing is brutally honest, but there are certainly occasions when utter transparency can do more harm than good, particularly to loved ones or to my own reputation. No book is worth losing close friends or family over.

The process of self-discovery that writing a memoir inevitably becomes has taught me much about the nature of memory and how it shapes the way we see and interpret our lives. There is bound to be much in The Exotic Rissole that may not be exactly accurate, but I probably wouldn’t be able to remember.

Tanveer Ahmed is the author of The Exotic Rissole, published by NewSouth.