World War II was an unusual period for Sydney’s underworld. On the one hand, lots of young potential criminals were out of the way in the army. On the other, there was a boost in demand for underworld services – illicit sex, alcohol and gambling. The city was flooded with Australian men on leave, who needed to spend a lot of money in a hurry, as well as thousands of Americans.

This was a bonanza for determined criminals, who – like Lennie McPherson – avoided conscription by pretending to work in protected industries. For old crooks such as Kate Leigh and Phil Jeffs, who like everyone else had suffered during the Depression, the good times had arrived again.

You might think such bad behaviour would have been kept in check by the dedication of most people to the war effort. But as World War Noir shows, that dedication was not nearly as widespread as the modern ‘War Memorial’ view might have us believe. Australia was only just emerging from the Depression and attitudes to the war were strongly conditioned by recent memories of economic deprivation. Service pay was meagre and to many, the idea of taking a pay cut to risk one’s life didn’t seem as obvious a thing to do as it does with hindsight. Ironically, there’s a lot more unanimity about the Second World War in Australia nowadays than there was at the time it was actually going on.

Many women, left to care for their children and take paying jobs, regarded their husbands not as heroes but deserters. The writers Dymphna Cusack and Florence James, in their Come in Spinner – a panorama of wartime Sydney – argued that it was women, not men, who bore the brunt of the war. Attitudes which resulted in massive industrial unrest on the coalfields, high rates of desertion from the army, an extensive black market and an upsurge of adultery and amateur prostitution, show that a large number of Australians were just not that supportive of the war. Compared with World War I, a much smaller proportion of servicemen actually suffered on the front line or as prisoners of war. (About half never left Australia). And far fewer died.

What many in Sydney did do was turn for relief to the pleasures offered by the illegal nightclubs, bookmakers, brothels and gambling rooms. Many younger criminals who would one day become famous got their start during this period, such as Richard Reilly, Abe Saffron, Chow Hayes and Paddles Anderson. The most successful were those who used force – murder if needed – to extract ‘protection’ payments from other criminals.

The key to their success was Australian prohibition, which is much less known than the notorious American Prohibition, but which ran for much of the Twentieth Century and shaped our underworld. The Australian version consisted of a series of restrictions on popular pleasures. Gambling on horse races was prohibited away from racetracks. Alcohol could not be purchased after 6.00pm or anytime on Sunday. There were also complete bans on paying for sex, abortion and homosexuality. What this did was create vast overlapping industries of illegal behaviour, and the men and women in this book thrived in those badlands, while overwhelmed police – charged in effect with suppressing human nature – either turned a blind eye or became corrupt.

World War Noir also looks at the bad behaviour of the Japanese and Russian spies in Sydney, and those Australians who supported them. For much of the war, Australians were terrified about a (non-existent) Fifth Column. In fact, our greatest internal weakness lay in the heart of government. The book tells the story of Frances Bernie, a secretary in the office of External Affairs minister Bert Evatt, who at lunchtime would take documents in her bag by tram down to Karl Marx House in the Haymarket. There – the headquarters of the Communist Party – the secrets provided by our unwitting British and American allies would be copied for Moscow, with Bernie then returning them to Martin Place.

World War Noir is about gangsters and the unique circumstances of World War II. It is also, along with the authors’ earlier volume Sydney Noir (about the 1960s), an exploration of the major role prohibition played in the lives of so many ordinary Australians. It is an alternative history of our biggest city.

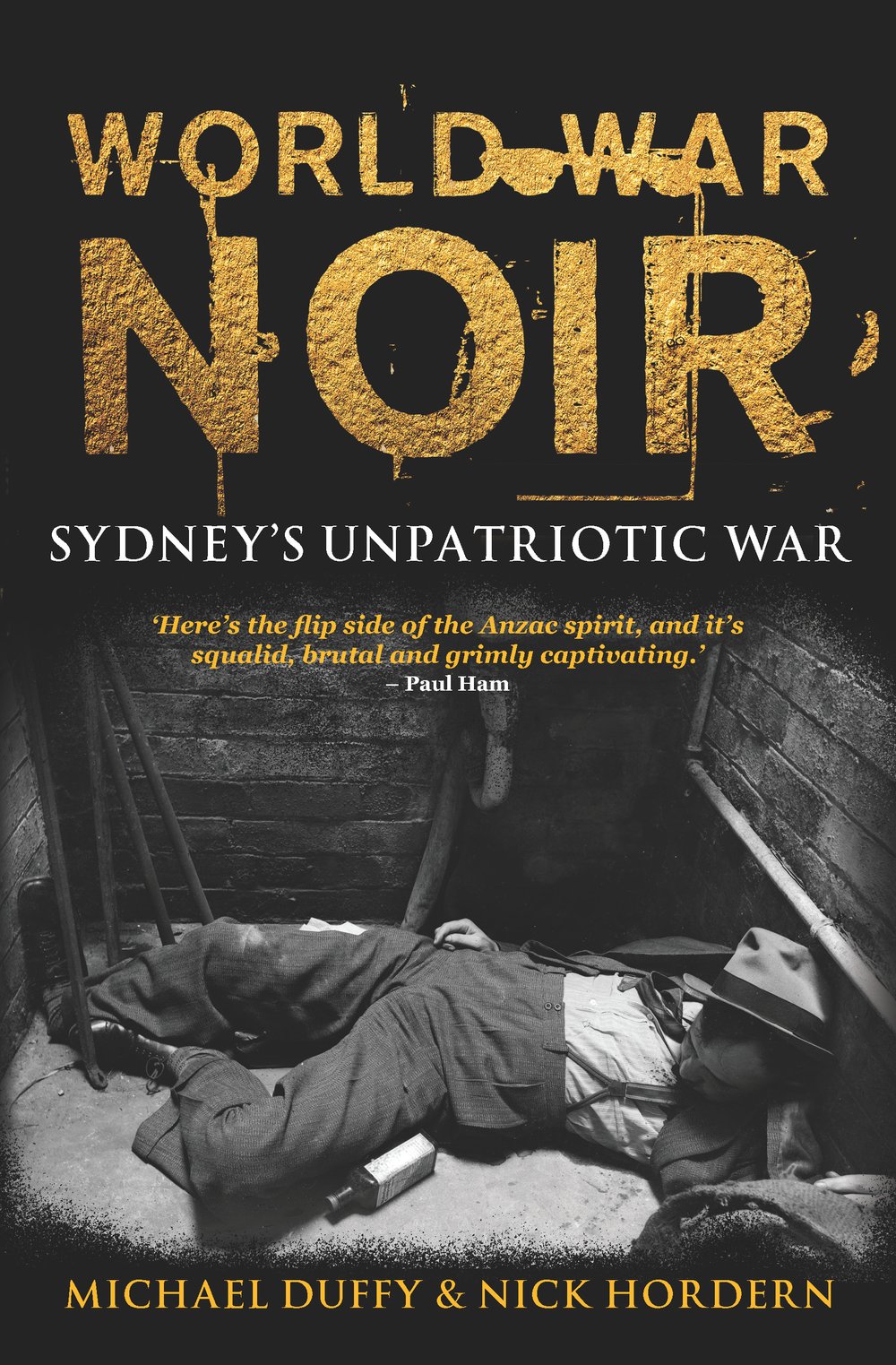

Michael Duffy and Nick Hordern's book World War Noir: Sydney's Unpatriotic War will be published by NewSouth in April 2019.