It’s the end of the drama. The results are in.

There’s a single character standing on the stage.

It’s 1993, Helena and I are in London at a performance by the National Theatre of David Hare’s The Absence of War. Watching, spellbound. After all, I’m Opposition Leader in the New South Wales parliament and this is a play about a Labour opposition leader in the UK, based on Neil Kinnock. And his fate.

He’s lost the election. He gives up the leadership and now he speaks direct to the audience, reflecting on the bruising experience:

I found myself asking a question which will always haunt us and to which no easy answer appears.

Is this history? Is everything history? Could we have done more? Was it possible? And how shall we know?

The stage directions require the company to remain frozen as the lights fade and the music swells.

These are questions anyone can ask, at the end.

Was it history?

Is everything?

Could we have done more?

***

Six years after I retired as Premier of New South Wales, Sam Dastyari, then secretary of the New South Wales branch of the Australian Labor Party, and his assistant secretary, Chris Minns, came into my office and said, ‘We have an idea.’ It was an idea suggested by a new planetary alignment, something unusual: a vacancy for Foreign Minister and a vacancy for Labor senator from New South Wales. Here was a possibility I could return to politics as Australia’s Foreign Minister, although with the high likelihood I would hold the job for a mere eighteen months. Another Prime Minister might have shrunk from inviting a former Premier aboard. Julia Gillard did not.

I see life as a learning experience and it would be hard – very hard – to deny oneself this. I got on board, signing up for the duration.

Six months later, in September 2012 during Leaders Week at the United Nations, advisers and I walked up First Avenue towards the UN headquarters at One United Nations Plaza. Autumn was settling. There were scudding clouds, wind in the air. Facing the UN, blocked off behind a massive police presence, was a big demonstration chanting under the direction of a leader with a megaphone.

His voice was high-pitched, the crowd’s response in rhythm, the total effect mesmeric:

Shame, shame, Ban Ki-moon.

Shame on the nations of the world.

The phrase ‘the nations of the world’ lodged in my prefrontal cortex like a shard of glass. The peoples of our battered planet are organised into nations. Foreign policy is to see that these – ‘the nations of the world’ – avoid going to war and manage some level of cooperation.

‘The nations of the world.’

What’s foreign policy, if not the conduct of all this?

In meetings at the UN I will seek the support of a majority of the nations of the world to place Australia on the Security Council for a two-year term. I will talk to them all: the old friends and our obvious partners as well as the small island states, the nations of the Caribbean, the nations of the Pacific and of the African world. Their response will be shaped by how they see Australia’s international personality.

There is a catastrophic descent into civil war in Syria and many of its twenty-two million people are suffering. Yet there seems no available mechanism for giving expression to the principle of Responsibility to Protect, endorsed here at the UN General Assembly in 2005.

Beyond the UN agenda – the multilateral arena – there is a debate within Australia’s leadership about our approaches to China and the United States. Three former Australian prime ministers – Fraser, Hawke and Keating – and some business figures and academic commentators say that in 2011 Australia tilted away from China. This is part of a wider discussion among nations in the region about how we will adjust to the phenomenon of the age: the re-emergence of China. And this re-emergence of China is part of a larger narrative about the shift of economic clout and strategic weight to Asia.

In Canberra the supporters of Kevin Rudd are unlikely to accept his departure from the cabinet that resulted in me taking his post and becoming Foreign Minister. Behind the tensions between him and Julia Gillard there lies a larger anxiety about the competence of a government lacking a majority in the House of Representatives.

To me, party ethos and leadership quality are at the core. Beyond this sits an even more fundamental question: whether the Australian Labor Party, like other social democratic parties, is in long-term structural decline.

We enter the foyer of the General Assembly. Foreign ministers followed by flocks of self-important officials, cutting across the public space like migratory waterfowl, as we convene – the nations of the world. Due to a political fluke I’m now part of this fraternity, the Foreign Ministers’ Club, which consumes such time and energy and may sometimes yield results.

In total it will be eighteen months to test what propositions hold, what fall by the wayside.

And to decide whether it was history.

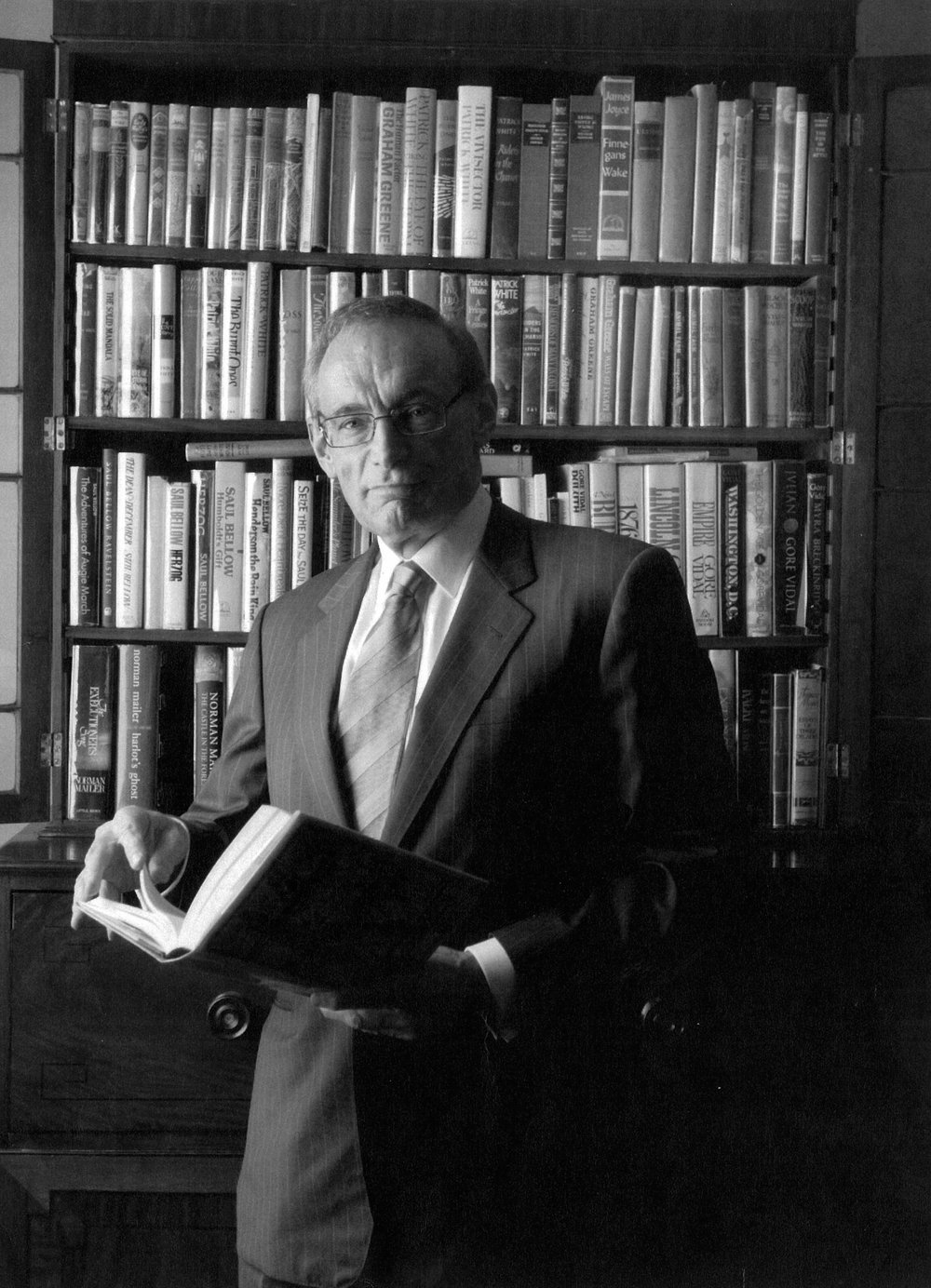

This is the Preface to Diary of a Foreign Minister by Bob Carr, out now from NewSouth.