Introduction

A year ago people would have told you it was impossible for school children to shift overnight to online learning; impossible for banks to offer mortgage holidays; impossible to double unemployment benefits; impossible to house rough sleepers or put a hold on evictions; impossible to offer wage subsidies, and absolutely impossible to get Australians to stay home from the beach and the pub.

In February 2020, as debate emerged about a new type of coronavirus, it seemed impossible that Australia would avoid the fate of nations similar to ours, which had hospitals straining under the weight of new infections and makeshift morgues in parks and public squares.

Yet many of our assumptions have been disproved. In some cases, we have done better than we could have expected. We have listened to medical experts and, for the most part, followed their advice. We have been disciplined and kind. We have risen to the challenge. We have put our lives on hold to protect the health of the majority.

Of course, there have been examples of high stress and bad behaviour: of panic buying and camera phone footage of fights in the toilet paper aisle of supermarkets. A few of these scenes got pretty ugly. Some people have refused to stay home when sick or refused to be tested. Some of the worst behaviour came from people proudly filming themselves behaving badly – arguing with police or shop assistants about their ‘human right’ not to wear a mask. But for every case of selfishness, there have been ten cases of love and community spirit, of patriotism and solidarity at its practical best. We are learning a lot about ourselves, bothgood and bad: thank goodness for Medicare; essential workers aren’t always paid according to their worth; insecure work and low wages are bad for everyone if sick people keep working or consumer demand drops across the economy; if you have a complex problem, it’s worth talking to an expert and listening to the science; our public servants aren’t all useless shiny bums; and if we want to be more self-reliant, we need a nimble manufacturing sector, preferably powered by cheaper, cleaner renewable energy.

Neither the health crisis nor the economic crisis caused by the virus are over, and it is still possible that things will get worse before they get better. Nevertheless, we have a responsibility to begin to consider the shape of the society and economy we want to rebuild. Australia will face massive questions over the next few years – questions as big as the ones we faced coming out of the Second World War.

After the sacrifices of the Second World War, the Australian government promised our suffering population full employment and higher homeownership, and they delivered. There followed many years of unemployment rates of around 2 per cent, and homeownership climbed by 10 per cent in just seven years.1

Wars, recessions, depressions and pandemics – all of them are devastating. All change societies and economies fundamentally. Changes that would usually take years happen overnight. Things that seem impossible become commonplace and necessary. The Black Death halved the population of Britain in the 1300s,2 but it led to the liberation of the serfs and paved the way for the industrial revolution.3 We can’t always prevent disaster, but we can determine how we respond.

What are today’s equivalents? People have sacrificed so much in 2020. Some have lost family members and couldn’t be at their bedside or even at their funeral. Hundreds of thousands of Australians lost their job or business. Children have fallen behindat school. Many of these sacrifices were because of governmentmandated shutdowns, which protected the health of our community but came with high costs. The sacrifices were necessary, but they were very painful. This discipline deserves a better future, not a ‘snap back’ to moribund growth and increasing inequality. Even before the pandemic we had almost 2 million Australians who didn’t have a job or enough hours of work, economic growth was weak, businesses weren’t investing and consumers weren’t spending. Wages growth was at record lows and our national debt had more than doubled.

Some will now reflexively demand tax cuts for big business and pay cuts for low-paid workers as a way of kick-starting the economy. Some will demand immediate cuts to government spending and our public services. The Government has already forced many to withdraw their retirement savings from superannuation just to survive. These are a recipe for a slower, more painful recovery, and a much less equal country on the other side. Instead, Australia needs strong, inclusive, environmentally sustainable economic growth. Good wages support confidence and demand in our economy. A well-paid, secure middle class is not the distant end-goal of economic growth: it is the precondition for it.

We should aim for full employment. That includes a strongly growing private sector driven by increased productivity and a fair, streamlined tax system. We must harness the intellect and inventiveness of our people. We need to invest in research and development, but also in commercialisation. We can be a country that makes things,

powered by cleaner, cheaper renewable energy. We shouldn’t turn our back on global trade, because we are an exporting nation, but it might be that supply chains are disrupted for some time and we need to have a greater capacity for diversification and self-reliance than we imagined.

We should invest in infrastructure that makes our cities and towns more efficient and more liveable, recognising that the way we will live and work in the future may have changed permanently as we discover we don’t have to be in the office every day or fly interstate for meetings. This infrastructure doesn’t have to be enormous in scale. Working with local government, our school system, TAFEs and hospitals, we can see the opportunities in every community for upgrading classrooms, community halls, footpaths and public toilets. It’s not glamorous – but it can deliver jobs in any community.

We shouldn’t be afraid of public sector employment. It is obvious, in just one example, that we need many more people working in aged care to look after the 100 000-plus people waiting for home care.4 There are so many examples in caring professions where the work clearly needs to be done and there are unemployed people available to do it. All that’s missing is the government commitment to training the workforce and paying a share of wages. People working in aged care, child care and disability services, for example, should be well-trained, with permanent work that is properly paid. Low-paid, gig economy type jobs in these sectors aren’t just bad for the workforce, they are bad for the vulnerable clients of these important front-line services. There could not be a clearer illustration of this than the spread of COVID-19 in nursing homes.

We can achieve full employment without giving up on fairness and environmental sustainability. A post-pandemic growth strategy should recognise that decent pay and conditions at work support stronger demand across the economy and more jobs in the long run. Before the pandemic, business profits were strong but wages were stagnant. When we share the benefits of growth more equally, growth is stronger and longer lasting. We don’t have to trash our environment for economic growth. In fact, we can invest and create jobs in protecting our environment.

We should work collaboratively with other nations for the common good – because good foreign policy doesn’t just protect our security, it supports our prosperity. A peaceful and prosperous region means a peaceful and prosperous Australia. We can’t fight a global pandemic without global co-operation. Australia’s response to HIV led the world. We can play a similarly positive role today.

Australians have had time to think about what matters to them: a secure job and a roof over their heads, but also connection with family, friends and community. COVID-19 is frightening and job-destroying and is hitting people unequally. But those of us who have stayed healthy (so far), who have a stable home

and a job, may find ourselves quietly admitting the guilty pleasure of enjoying some elements of lockdown. People whisper to each other, ‘It’s actually good working from home. I don’t miss being stuck in traffic for hours every day’, ‘I love having dinner with the kids every night’, ‘It’s great to cook at home more, and not have the pressure of running from one appointment to the next’, ‘I love not having to travel interstate for work, being away from the kids’, and ‘Have you seen the night sky? Less pollution means you can see the stars’. People who aren’t so worried about their health or their jobs confess to each other that there is good stuff that comes from slowing down. How can we capture the benefits of a less pressured life, while still having high consumer confidence, greater business investment, improved productivity and the strong economic growth that supports jobs? Of course, it is a complex formula to get right – but think of what we have already achieved.

As we begin to rebuild, spending hundreds of billions of taxpayers’ dollars, we need to think of the society and economy we are bequeathing our children and grandchildren. After all, they will be the ones paying for it. We need ‘all in this together’ to last longer than the lockdown.

What’s at stake here is not just economic growth, and a cohesive community. We are fighting a battle for democracy. Research into the effects of previous pandemics across 142 countries shows young people can lose trust in political processes for decades after exposure to the crisis.5 The effects of pandemics linger, and not just in the scarring of long-term unemployment.

In a democracy, government is a vehicle for collective problem solving. If we can’t solve the social and economic problems that face us today, we will see a continuing decline in people’s faith in our democracy itself. Research organisation Freedom House, established by Eleanor Roosevelt and others in 1941, has found that the world is in the 14th year of a democratic recession.6 We have seen the rise of divisive and autocratic populists who have an answer to every complex problem that is ‘neat, plausible and wrong’. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama and others argue the key to success in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic is ‘whether citizens trust their leaders, and whether those leaders preside over a competent and effective state’.7 Unless we can provide economic growth that is sustainable and inclusive, and the jobs that come with it, we are neither competent nor effective and we will be breaking faith with citizens who have sacrificed so much.

Australians have been relieved as their politicians have put conflict to one side and focused on the national interest, taking the advice of experts when dealing with the health crisis. We can’t let that go. We need to bring a spirit of open-minded thoughtfulness and co-operative problem solving to the other big issues that face us, like full employment and climate change.

Former prime minister John Howard talked about being relaxed and comfortable. There’s something in that. Most of us long for a time when we aren’t looking suspiciously at every door handle as a source of potential deadly infection, when we aren’t worried about how to pay the rent or the mortgage.

But we should aim a bit higher, because ‘relaxed and comfortable’ sounds like we are being encouraged to avert our gaze from the complex or difficult. We should aim for relaxed and confident. We want people to have the confidence to spend and invest, knowing they will have a job next week and next year. People should be confident that if they work hard and do the right thing they will get ahead. They should be confident their children will have a better life than they had. We should be confident that our bush and reef will be there for future generations. We should be confident of our values as a nation and our place in the world. We should be confident that we can withstand the next shock and, if we fall on hard times, that we’ll get the help we need to get back on our feet.

In a thought-provoking piece for the Financial Times, Indian author Arundhati Roy said, ‘the pandemic is a portal’:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, and data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.8

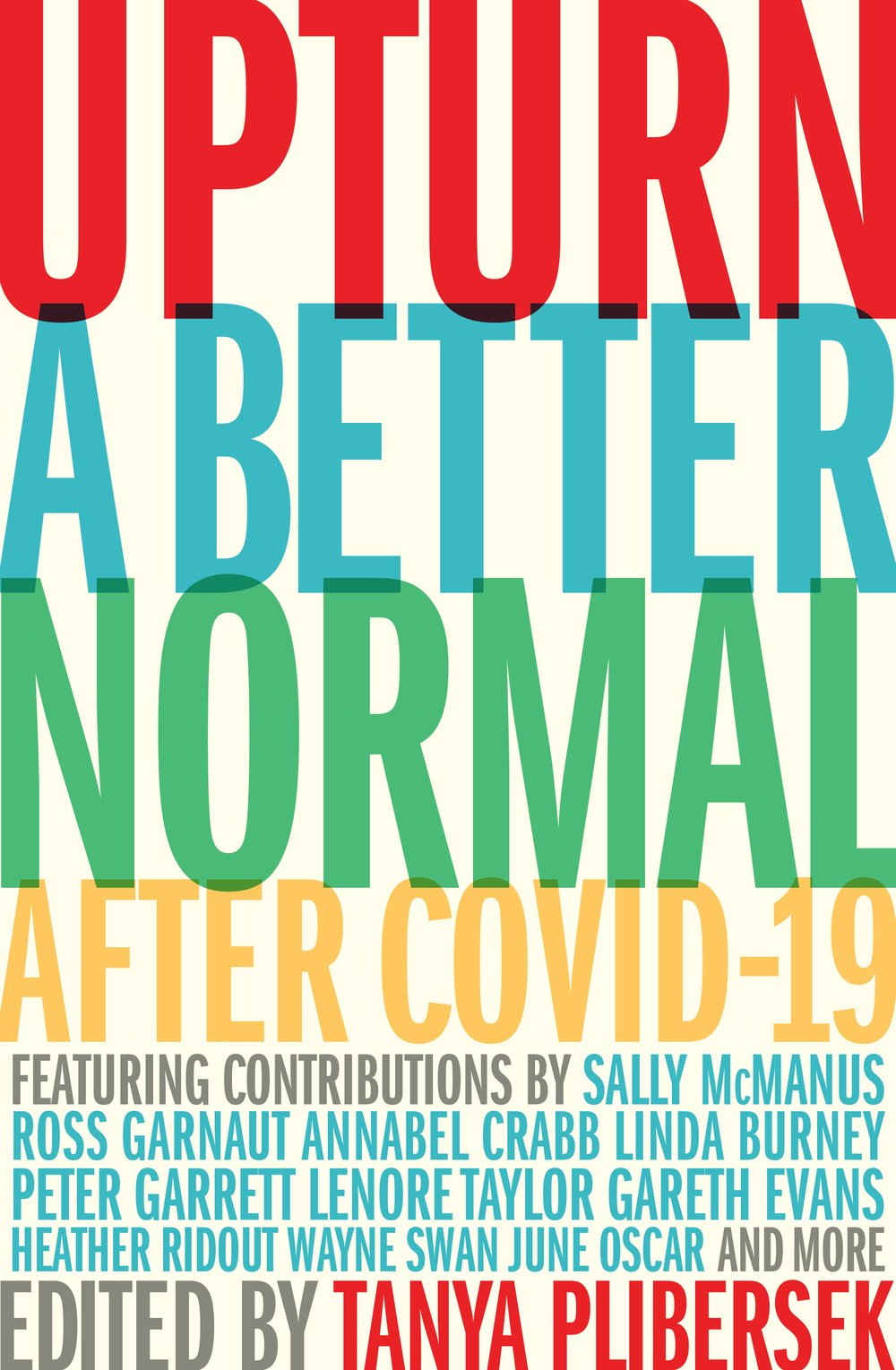

On the following pages you will read the work of some of Australia’s most interesting thinkers, who are ready to imagine a better Australia, and to fight for it.Tanya Plibersek's edited collection Upturn: A better normal after COVID-19 will be published by NewSouth in November 2020.Notes:

1 Andrew Leigh, ‘Reducing Inequality through Reconstruction’ in Emma Dawson and Janet McCalman (eds), What Happens Next: A Handbook for the Reconstruction, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2020.

2 Caroline Barron, ‘Post-Black Death: a “golden age” for medieval women?’, History Extra, 8 June 2014, <www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/medievalqueens-of-industry/>.

3 ‘The Black Death led to an improvement in agricultural technology, changed the status of women, and increased wages. This process helped the Industrial Revolution’, Peter Temin, Professor Emeritus of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, <voxeu.org/article/economic-history-and-economicdevelopment#:~:text=The%20Black%20Death%20led%20to,profitable%20in%20low%2Dincome%20countries>.

4 Dana McCauley, ‘Morrison announces 6100 new home care places, 100,000still waiting’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 July 2020, <www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/morrison-announces-6100-new-home-care-places-100-000-still-waiting-20200708-p55a51.html>.

5 Cevat Giray Aksoy, Barry Eichengreen and Orkun Saka, ‘Young people exposed to Covid-19 can lose trust in politicians for decades: Study’, Print, 15 July 2020, <theprint.in/opinion/young-people-exposed-to-covid-19-can-lose-trust-inpoliticians-for-decades-study/460508/>.

6 Sarah Repucci, ‘A leaderless struggle for democracy’, Freedom House website, <freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2020/leaderless-struggle-democracy>.

7 Francis Fukuyama, ‘The thing that determines a country’s resistance to the coronavirus’, Atlantic, 30 March 2020, <www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/thing-determines-how-well-countries-respondcoronavirus/609025/>.

8 Arundhati Roy, ‘The pandemic is a portal’, Financial Times, 4 April 2020.