Extract of the Introduction from Turmoil: Letters from the Brink by Robyn Williams

I did not expect to be here

I did not expect to be here like this. My Williams family is short-lived and I have exceeded their span by an embarrassing chunk. So here I am, in what I thought would be my twilight years, as fit and busy as ever; the brain beneath the grey thatch and the wrinkles still pretends it’s 18. I’m enjoying every precious moment and look back on a life that’s unfolded in a way that seems almost scripted: one golden period after another.

Until now.

Today’s uncertainties were not in the script. I knew the world faced challenges, global ones, but I also knew that smart people with huge determination were ready to face them. As a society we were becoming more civilised and sensitive to others; we thought we understood the nature of his and hers, girl and boy, friend or foe, truth and lies. No more. It’s a shouting match — and the good guys can’t match the bullies’ megaphones. Look at science. It is treated with disdain by the funders and the ‘deplorables’ alike. Presidents and captains of industry call climate science ‘a hoax and a fraud’. Shock jocks and columnists, expert at stoking grievance, make ordinary people feel cheated. They turn decent folk into people some of us would, yes, be willing to deplore. Briefly. When I was growing up they were family.

It’s also hard to know when you’ve done well. So many friends and colleagues get fired, so many brilliant young men and women can’t get jobs (unlike the way I did in one go, walking off the street in 1972), so many ‘great leaders’ become great wimps. Captains of cricket resign in tears.

And as for those political labels thrust on people as if they are a regrouping of the Bolshevik plot of a century ago, no headline or incendiary paragraph is complete without the word left looming like a threat to your continued wellbeing. This was one I saw, among many, in an editorial:

… this simple undeniable truth sits at the very heart of the great climate change con job. Reality stubbornly refuses to do what the left has so hysterically promised and foretold it will do.

My communist father would have pissed himself with acid amusement at the genteel, mild-mannered — even earnest — souls of the scientific community being labelled as socialists, followers in the tradition of Che, Gramsci or Red Ellen. Left? Not even pink!

This is not the last act I expected, to see public discourse in this state. To see ignorance lauded and scientific research regarded as an optional ‘belief ’. Much worse, this is not the fate our gorgeous and largely benign civilisation deserves. The disparagement of science is an affront to the sublime beauty and complexity of the natural world that we have only recently begun to comprehend.

There is a striking disjunction in Australia. We have some tremendously talented people, young and old, keen to do good work and collaborate effectively. But we also have institutions and leadership that are, in the main, dreadful, gutless and dull. Why is this so? Should we all become New Zealanders?

The chapters that follow are reflections on this turmoil from a personal point of view. Are we facing an age of confusion and failure? A prelude to the kind of collapse that Jared Diamond writes about, but this time on a global scale? Or is this merely a short interlude, a transitory spell in the armpit of history before a new creative generation arises, no longer willing to dally with the squalor of present headlines?

These reflections focus on what may seem to be a collection of random topics: success and failure (where is the boundary between pleasure and pain?); hatred and evil (do you just give up amid the turmoil of loathing — is there a better way?); personal loss (grief can perhaps be the greatest turmoil of all); and Oxford and the Australian bush, two places I know and love and where the turmoil dissipates immediately and serenity comes quickly.

I’ll admit that this is very much an attempt to convince myself that the turmoil, this age of venom and spite and ignorance, is transitory. It cannot last because it is self-destructive. People are too good. My parents were right, in their idealism at least.

In February 2017 I walked in the sunshine through the glorious campus of the University of California, Los Angeles, and watched student after student, mostly young women, walk past me with their heads down over the screens in their hands. Finally, along came one who was looking up and admiring the trees, some of which were Australian eucalypts.

‘Good morning,’ I said smiling, though fearing she would call the campus guards to protect her from my unwarranted intrusion. ‘Why aren’t you examining your phone? Why are you the only one looking at the lovely landscape?’

She smiled back, totally friendly. ‘It’s a beautiful morning,’ she replied. ‘I’m enjoying it.’ I told her I’d just landed from Australia and she wished me well.

A simple encounter, but significant. A generation is beginning to look up from the tyranny of its gadgets and the confusion of its polity. Schoolkids are saying no to guns. They are turning back to books with pages. Evidence is coming in that they want to emerge to the world, if given the chance. And so, I am confident that my final personal chapter, Act Seven, is going to be OK after all. The first acts, all remarkably positive and forward looking, will not be crowned by an anomalous crunch.

Or am I wrong?

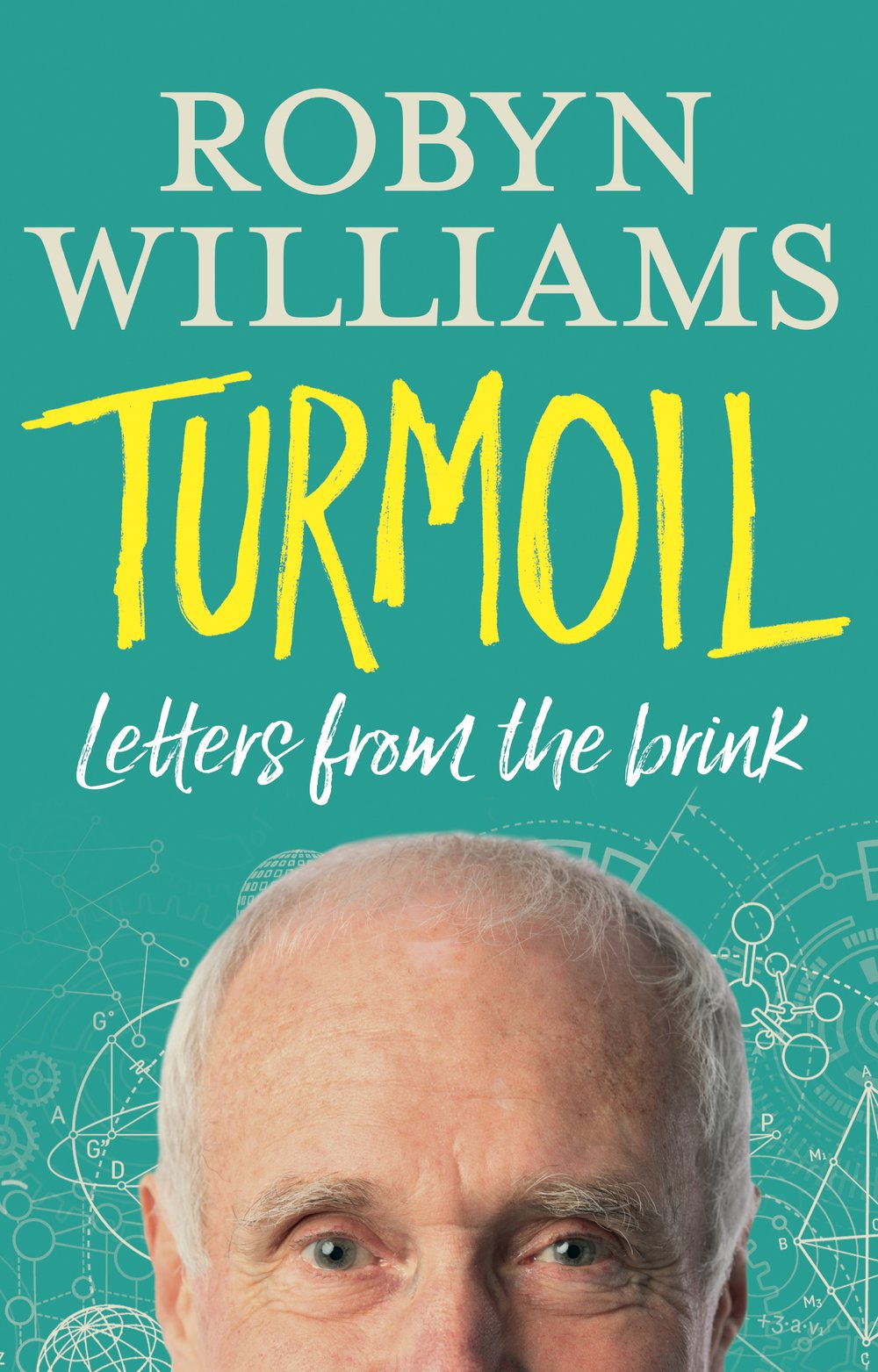

Robyn Williams' book Turmoil: Letters from the Brink was published by NewSouth in September 2018.