Recently when I was in Canberra for the launch of Ian Chubb’s Science Strategy, the Minister for Industry Ian Macfarlane reminded us all that we should all try harder to communicate a vision for science. He isn’t the first politician to remind us of this and he is right.

Fortunately things are getting better. Not everyone will agree with me. It’s hard to see the improvement because it’s been gradual – but you can see it if you look back far enough.

Let me demonstrate this by quoting a piece of very, very old science writing that involves a politician and a scientist. It is a good one. I’m not sure how many of you will recognise this passage. It begins like this:

Fuit tamen faber qui fecit phialam vitream, quae non frangebatur. Admissus ergo Caesarem est …

You will only recognise this if you are as old as me and studied Latin at school, or if you are even older and are a Roman citizen. But if not, here is the full version – this time not in Latin but translated into Australian.

Once there was an inventor who made a pot out of a type of glass that couldn’t be broken. He was admitted to show this creation to Caesar. He held it up, then dashed it against the marble floor. The craftsman then retrieved it and showed how it was dented – just like a metal bowl would have been. Then he took a little hammer out of the fold of his toga and beat out the dent completely without any trouble.

He smiled, thinking he would soon be rewarded. Caesar said to him, ‘Does anyone else know how to make malleable glass like this?’

The craftsman explained that no one else in the world knew the secret.

Caesar immediately ordered his head be chopped off – as he feared that if this invention were known all his own glassware and even gold pots would be rendered worthless.

This passage comes from the Satyricon of Petronius and was written around the time of the Emperor Nero in the first century AD. And at once you’ll see that science communication and politics has come a long way.

Let’s have a quick look at what we learn from this piece. The first thing is that the inventor should obviously have published. I think this is where the ‘publish or perish’ rule originated.

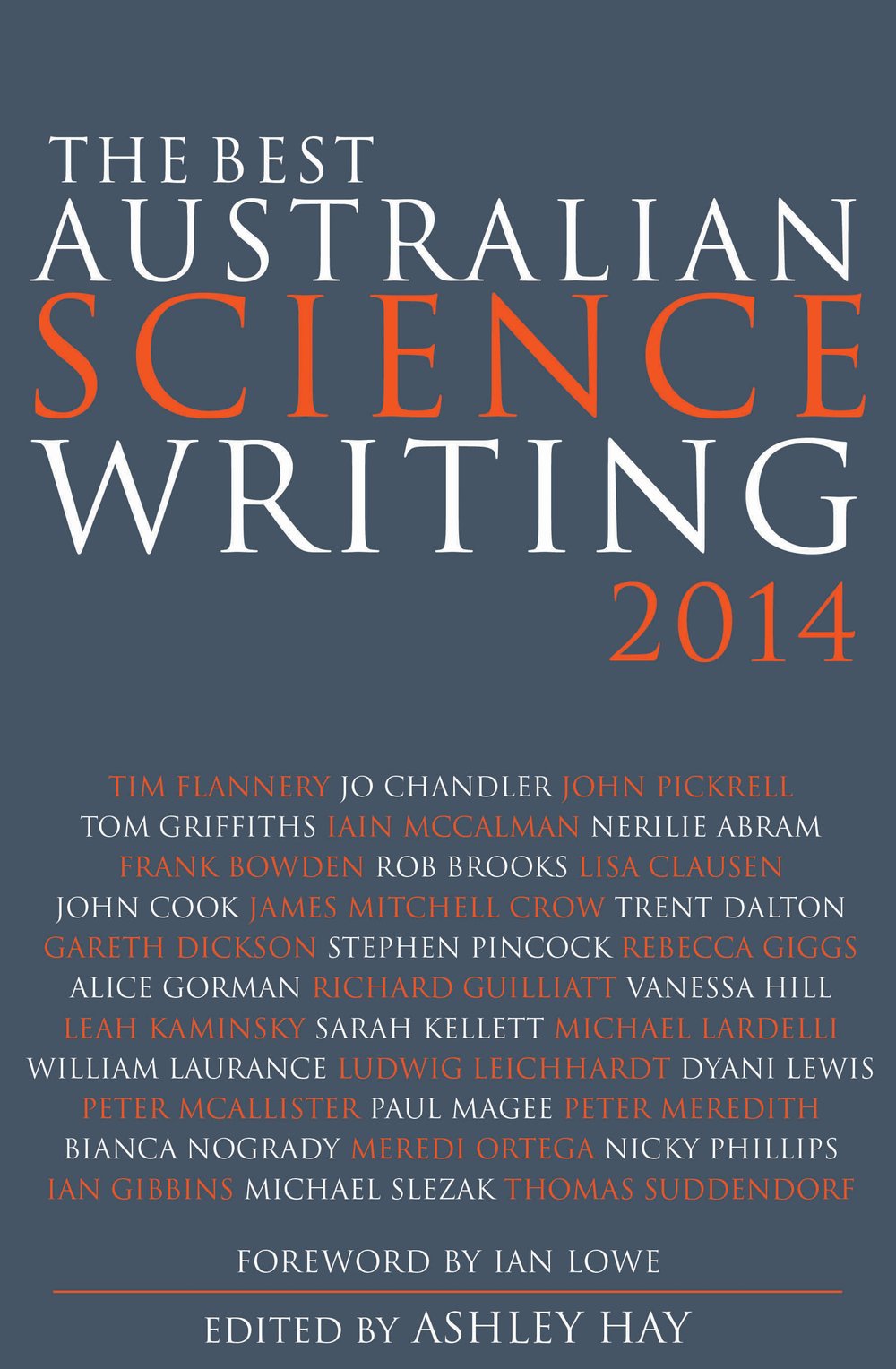

That hasn’t changed but other things have. Firstly, this piece was in Latin. Today very few of my science lectures are in Latin. So that’s a big thing. None of the stories in The Best Australian Science Writing are in Latin either, nor will you be swimming in technical jargon.

Another improvement is that we no longer chop off the heads of scientific messengers – even if they bear inconvenient truths. It is true that climate scientists are sometimes criticised by senators but only very rarely are they vilified by emperors. The problem was a bad one but I now believe it is considered poor form to attempt to intimidate scientists and I hope things continue to improve.

In fact very few scientists are ever intimidated. More and more researchers in all fields are genuinely embracing science communication and are using new and unstoppable technologies to communicate.

At UNSW many of the staff in Science have large followings on Twitter, Facebook, on You Tube and on our special channel UNSWTV.

And our commitment to science communication and community engagement is both bottom-up and top-down. In a top-down sense UNSW Science supports the Australian Science Media Centre, The Conversation, RIAus, and as well as supporting this annual book launch we hold the annual UNSW Medal for Science Communication, which this year was awarded to the BBC’s favourite geologist Iain Stewart.

We believe that getting information out is critically important. At UNSW we have an Easy Access IP model that allows us to engage with industry, and we offer free courses to the world via MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses).

If I am ever asked by an emperor, ‘Does anyone else know the secret?’, my answer may well be ‘Thirty thousand people in the case of our new physics MOOC and two million in the case of the maths videos which are in the top ten in the world’.

If we can sell thousands of copies of The Best of Australian Science Writing we will all keep our heads.

All this communication is critically important. High-quality science writing is not – as it happens – the only thing on the internet. It is important that scientists are out there to correct and counter nonsense that is driven by self-interest at worst and plain ignorance at best.

Democracies need information and engaged scientists and science writers can help provide high-quality information. At this moment in time Western democracies are stalling, weighed down by their own inertia and the white noise of stalemate.

Science provides new information, and scientific information can shift the balance and drive change and reform. I am grateful for the work of all those writers who help to spread science and scientific thinking.

But there is one final thing I will say. The other bad thing about the 2000-year-old piece from the Satyricon was its ending.

All my life I have wondered if anyone would re-invent the unbreakable glass, but I have never found such a substance (though I have tested many glasses). And I also felt a bit sorry for the inventor. At every level it is a very sad and tragic story – it did not have a happy ending.

And the main purpose of science is to make sure that endings are as happy as they can be. The world is a tough place but science has made it happier. Science has enriched humankind in a material sense but it is also good fun. The stories in this year’s book are fascinating and uplifting. Science provides detail to the tapestry of life and offers another dimension to share and enjoy.

This is an edited excerpt of the speech delivered by Professor Merlin Crossley, Dean of Science, UNSW, on 6 November 2014 at the prize ceremony of the 2014 Bragg UNSW Press Prize for Science Writing and the launch of The Best Australian Science Writing 2014. The Best Australian Science Writing 2014 is out now from NewSouth.