In March, Australian satirical news website The Chaser declared ‘Oh fuck’ the Word of the Year for 2020. ‘It now accounts for 50% of all words used in the English language’, they commented. And since it was already a clear winner, why wait until the end of the year to declare it the year’s most prominent word? As someone who often fronts the Australian Word of the Year (as decided by the Australian National Dictionary Centre), I particularly enjoyed this story. It might have been meant as satire but it felt pretty true – 2020 has been a year to inspire more than a few swear words, and it’s not over yet.

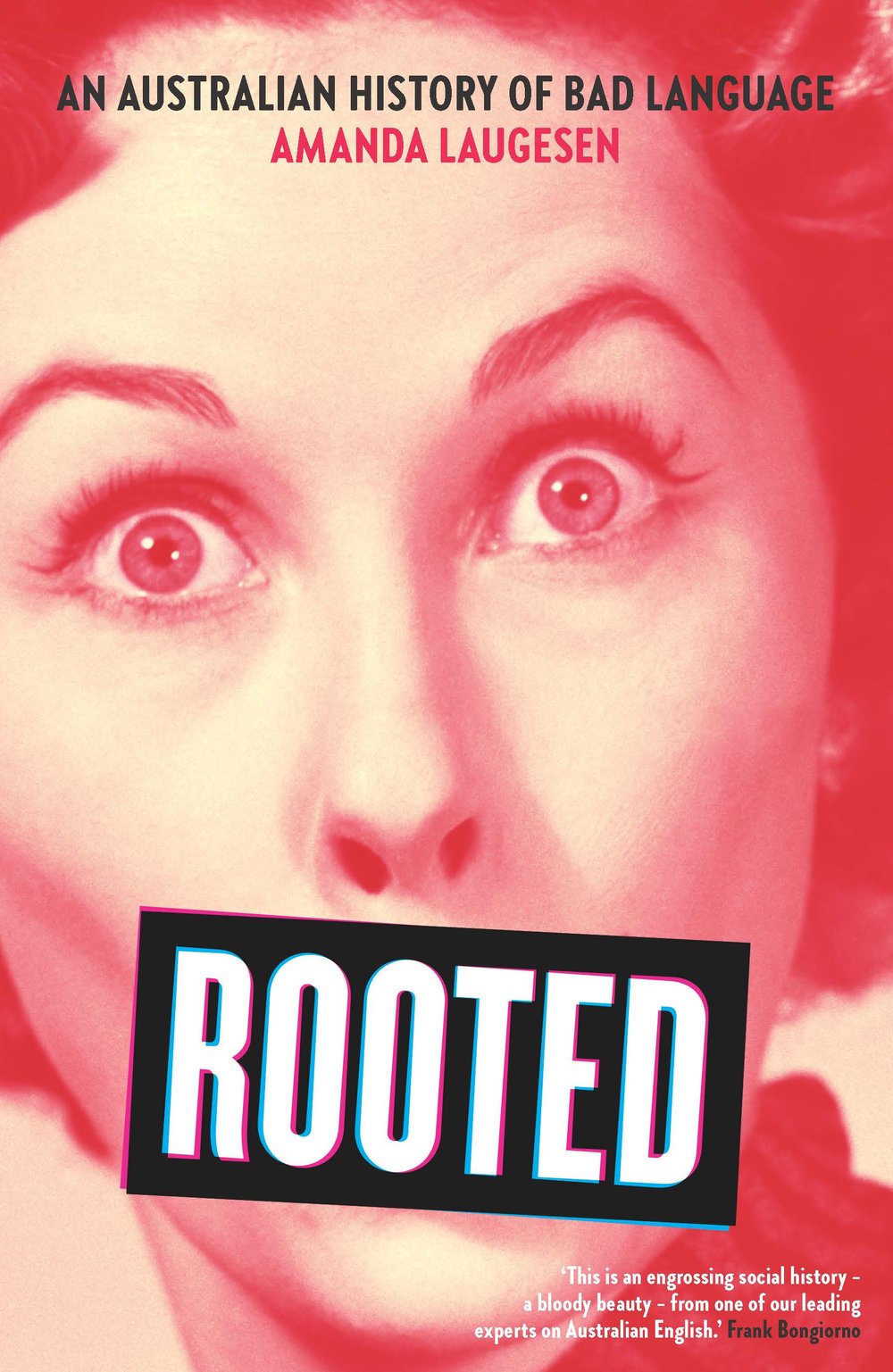

My book Rooted: An Australian history of bad language tells the story of bad language in Australia from invasion through to today. It explores the words themselves from the ‘bloody’, ‘bugger’ and ‘damn’ used by the convicts and marines, to emoji swearing used on social media. But it also explores the ways in which bad language has shaped our social relations, our laws, and our cultural mythologies.

A few themes developed as I was writing this book. The first was about power. This was not just the power of the words themselves but also about who has the power to use bad language and who is condemned and censored for using such language. One of the stories that most stood out for me was the story of a woman named Vera who wrote in to the women’s liberationist newspaper Mejane in 1971. She complained of how men were always telling her that feminists should stop swearing if they wanted to be taken seriously. She also recounted how she had been arrested at an anti-Vietnam War rally for saying the word ‘fuck’. Vera asked how was it possible that a middle-class woman swearing was more offensive than children being napalmed in Vietnam? This story touches on so many issues that my book explores: what we find offensive and why, the fact that women swearing is considered ‘improper’ but men’s swearing is not treated the same way (unless they are Indigenous), and that swearing can also be a form of resistance and subversion.

Another theme that I take up in the book is the way Australians have seen themselves as the kind of people who swear more, or at least more creatively. There are certainly many swear words that are distinctively Australian: think ‘pig’s arse’, ‘bloody oath’, or ‘get rooted’. ‘Fuckwit’ is an Australianism, first recorded in Alex Buzo’s play Front Room Boys (1969). We also lay special claim to the ‘four B’s’ – ‘bloody’, ‘bastard’, ‘bugger’, and ‘bullshit’. We have shaped a strong cultural mythology around our propensity to swear, and cultural figures such as the bushman, the bullock-driver, and the digger at war have all been celebrated for their robust and voluble swearing. But as I suggested above, only some Australians can swear without paying a price.

And despite the celebration of swearing, censorship and punishment were also themes that were threaded through my story. Censorship inspired creative ways to disguise swear words, and led to the many challenges to the censorship regime mounted in the 1960s and 1970s by characters as diverse as playwrights Alex Buzo and David Williamson, and student activists such as Wendy Bacon. While we have become increasingly tolerant of swearing in many contexts, swear words are still disguised in print and, depending on the timeslot, bleeped out of television and radio programming.

Our bad language and attitudes towards bad language can tell us much about our preoccupations, our identity, and our anxieties. This has also been true of another sort of bad language – the slurs and epithets that have been very much a part of the Australian English lexicon through the years. While in the past many of the words that make up the vocabulary of discriminatory language were not considered offensive by the dominant society, they shaped a racist, sexist, and homophobic language that impacted lives. The targets of this language were stereotyped by such language, and felt the pain of abuse and discrimination. This history forms the basis for why discriminatory language should no longer be acceptable in any form, and why it’s the taboo language of today. It’s not just a matter of ‘wokeness’ but rather of respect and acknowledging the historical weight of discrimination that is attached to such language.

Language is a fascinating way of thinking about our history and our identity. But thinking about the complexities of the history of our language and how we use it can help inform our understandings of what makes a civil society, and what place, if any, censorship of language should have. We should think long and hard about why Australians tolerate First Nations people being disproportionately the target of offensive language crimes; we should wonder why we care so much about someone saying ‘fuck’ on television but tolerate bullying from our leaders; and we should think about why we too often dismiss the goal of using dignified language as ‘wokeness’ or ‘political correctness’.

Amanda Laugesen's book Rooted: An Australian history of bad language will be published by NewSouth in November 2020.