When Plastic Free July founder Rebecca Prince-Ruiz made a commitment to try to avoid single-use plastic a decade ago, the decision started at her bin. In the first half of 2020, a year of unexpected change, the humble bin has been in the limelight again, though for very different reasons. Aussies, their laconic sense of humour coming to the fore during the pandemic, used their weekly bin outing as an opportunity to dress up in outlandish costumes, the theory being that our bins were going out more than we were.

Humour aside, this year’s Plastic Free July may be more of a challenge than usual as some alternatives to single-use plastics are less accepted than in previous years. The way we navigate our social and working lives is vastly different to the status quo of just a few months ago, but rather than seeing this as a negative, it is a clear demonstration of just how resilient and inventive we can be. It also illustrates how important the decisions we make are, and how much they can impact ourselves and others.

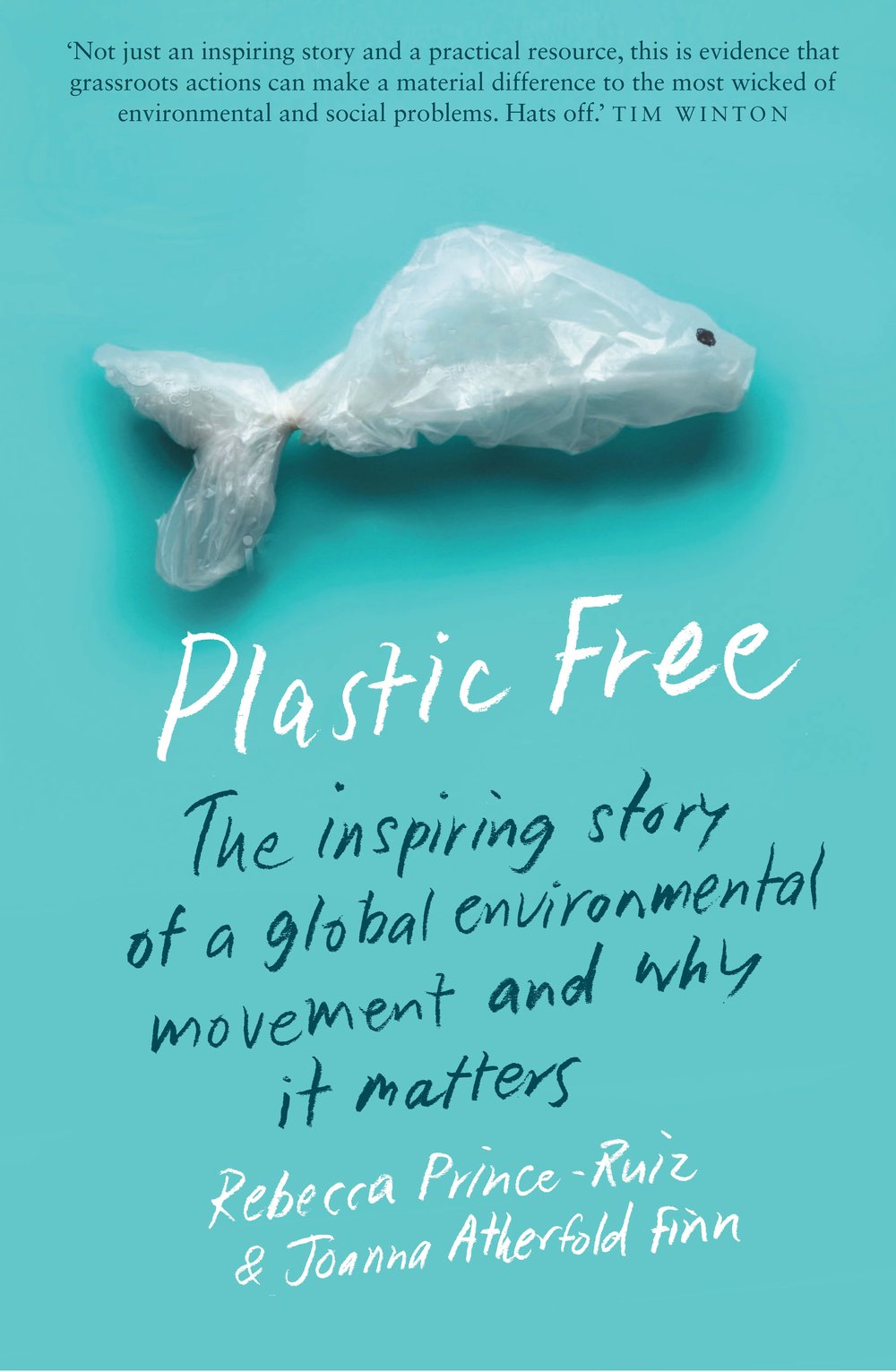

Plastic Free: The Inspiring Story of a Global Environmental Movement and Why It Matters is, at its heart, a book about how ordinary people can make extraordinary changes. It tells the story of Plastic Free July, a social phenomenon involving over 250 million people in 177 countries. Most importantly, it shows how a determined community can be a formidable force.

The story opens with a simple question from Rebecca: ‘I’m going plastic free next month. Who wants to join me?’ and charts the journey as that small group of people who said yes branch out into one of the world’s most successful environmental movements. But why does the challenge capture so many? What can we learn from it?

The answers are explored through the stories of people from Australia and around the world who have had their own ‘penny drop’ moment, as Rebecca did when she visited her local recycling centre: ‘the end-of-life point of human production and consumerism.’ It was there that Rebecca grasped an uncomfortable understanding of where her plastic packaging went when she threw it ‘away’. She realised something that had been teetering around the edge of her consciousness for some time: ‘The heart of the problem is how much we consume, and we can’t recycle our way out of it.’

Although Plastic Free is solutions focused, it doesn’t shy away from exploring how we got to the point of being a ‘throwaway society’ in a relatively short period of time. Just last year, we were consuming almost twice what the planet can sustainably produce in one year. It’s a sobering statistic and one that has clear implications, not only for ourselves, but our environment. Although most plastic pollution comes from the land, its effect on our waterways and the living creatures that rely on the ocean for survival (including ourselves) is indefensible and unsustainable. As Rebecca says: ‘No one is okay with this.’ The book features stories from scientists, environmentalists, educators and everyday individuals and families that are using that ‘not okay with this’ momentum and making a difference through research programs, clean-up initiatives, plastic-free alternatives, education and individual acts that, when combined, send strong messages to governments and corporations.

As the Plastic Free July challenge has grown, so has the variety of solutions, showing how small actions can make a huge impact, one step – and piece of plastic – at a time: ‘Proof,’ Rebecca says, ‘of the incremental power of small changes and grassroots action.’ Those changes and ‘tips’ for taking on the challenge are shared throughout the book from people around the world who have significantly reduced their waste. There is something very rewarding about being proactive and taking back control through our decisions. In this way, although Plastic Free will equip readers with many ways to work towards being single-use plastic free, it is also a handbook that can adapt to other change-making endeavours. Behavioural economist Colin Ashton-Graham, among others in the book, provides strong evidence of the effectiveness of a ‘hands leading the head’ approach. Colin attributes much of the success of Plastic Free July to the way the campaign embodies ‘best practice’ in behaviour change, something Rebecca and her team were doing long before it was formally acknowledged through the principles that Colin describes.

This brings us back to that idea of change. As the final edits of Plastic Free were taking place, the world was thrust into the unknown and almost unbelievable scenario of a pandemic. As events unfolded, each day seemed to bring new uncertainties – an unfathomable shortage of toilet paper being one of the more peculiar ones. Rebecca asked herself and her colleagues what this would mean for the direction of Plastic Free July. Obviously health considerations overrode any other concerns. Avoiding plastic would be a greater challenge than ever before. Plastic Free July participant Wendy provides an interesting perspective: ‘I think people that have been active in plastic reduction seem to be managing a lot better … They’re used to adapting and using creativity to navigate problems that arise.’ Rebecca described it as almost coming full circle, back to the early days of Plastic Free July. ‘We didn’t know the answers to every question, but we shared ideas and learned as a community. We were in this together.’

People may have stopped dressing up to take their bins out, but what’s inside that bin is up to each of us. The information in Plastic Free will lighten the load of your weekly bin, and in turn lighten the load on the environment. There is a role for everyone and we hope you will take on the challenge with us.

Rebecca Prince-Ruiz's and Joanna Atherfold Finn's book Plastic Free: The Inspiring Story of a Global Environmental Movement and Why It Matters will be published by NewSouth in July 2020.