How are several Australian artists and some of our major cultural collections linked with the works of great eighteenth-century Italian printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–78)? Much of Piranesi’s Grandest Tour: From Europe to Australia tells a fascinating, previously untold story, while also providing Australian audiences with a comprehensive introduction to the artist that takes account of recent research.

American curator Andrew Robison describes Piranesi’s work as ‘extraordinary in composition, expression, draughtsmanship, tonality, texture and technique – not only in the history of graphic art but in the history of all the arts’, and identifies him as ‘the most important artist to make his reputation almost entirely on the basis of his prints’.

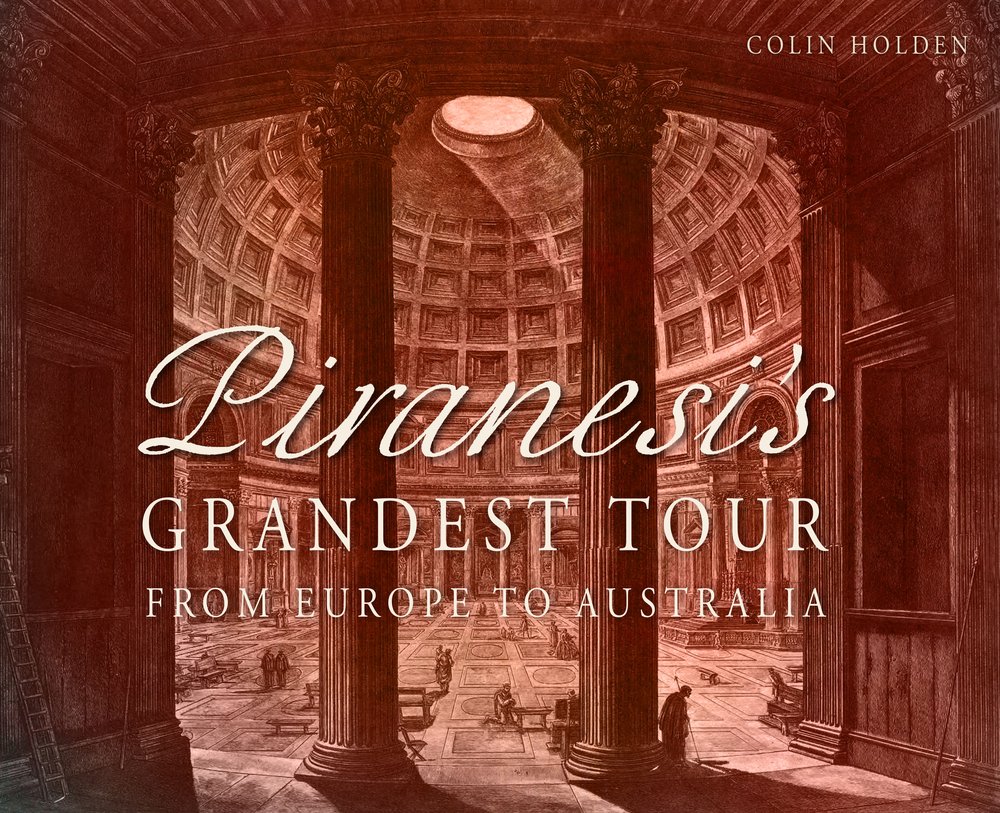

Rome was central to Piranesi’s reputation and practice. He secured international fame in 1756 with his Antichità Romane (Roman Antiquities), a detailed four-volume treatment of classical monuments. His Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome), comprising 135 unusually large prints, have since become iconic images of that city. The many plates in the book reproducing images of both baroque Roman streetscapes and classical ruins may well give readers the illusion that they are visiting eighteenth-century Italy themselves. Despite a serious documentary interest, Piranesi’s art transcends archaeology and underlines the emotional power of memory. His vision turned ruins into studies of psychological intensity; the momuments themselves are transformed into dramatic actors with which viewers can identify.

The book’s title refers obliquely to Piranesi’s original audience, who visited Italy as part of the ‘Grand Tour’ – travel across Europe by the well-to-do, professionals and scholars seeking cultural enlightenment and education. Piranesi sold his work to them from an elegant museo (showroom) near the Spanish Steps in Rome. Though Australia was not on the world map as a nation when Piranesi died, by the middle of the nineteenth century, Australian collectors and institutions were beginning to acquire whole sets of his prints. One cultured Melburnian, James Alipius Goold – the city’s first Catholic archbishop – had quite personal reasons for acquiring them: he had trained and worked in Italy for half a decade before coming to Australia. A pair of folios given by English donors to the State Library of Victoria during the Great Depression embody the standards of Grand Tourists. Bound in magnificent leather and gilded binding by King George IV’s bookbinder, they contain almost 150 of Piranesi’s prints in lifetime editions, including many first editions.

Piranesi’s Grandest Tour concludes by showcasing the many different ways that echoes of Piranesi can be detected in works by Australian artists from the Federation years to the present. Rick Amor, and printmakers such as Marco Luccio and Ron McBurnie, reflect Piranesi’s intensity and sombreness, while others such as Angela Cavalieri engage with its documentary dimension. One of Fred McCubbin’s most celebratory paintings again has its inspiration in Piranesi.

Piranesi’s Grandest Tour also includes what is probably the most detailed introduction in English to the key figure in maintaining public awareness of Piranesi’s work after his death – his eldest son, Francesco (1758–1810), apparently a workaholic and able businessman. At the end of the eighteenth century, Francesco’s public involvement in republican politics forced him to flee to Napoleon’s Paris, where he published an important posthumous edition of his father’s work.

Piranesi's Grandest Tour: From Europe to Australia by Colin Holden is published by NewSouth (February 2014). The exhibition at the State Library of Victoria, Rome: Piranesi's Vision, curated by Colin Holden, runs from 22 February to 22 June 2014.