I can remember precisely when my passion for the past began. As a young child of five holidaying in Sydney from my home in Dubbo, my parents took me to the Australian Museum on College Street. I was transfixed by an exhibition of early human evolution. The panoramas displayed scenes of ancient life, people gathered around waterholes sharing a meal with the weapons and tools they relied on sitting nearby. That night I remember looking out on a sandstone rock pool next to where we were staying and imaging my life in the Sydney bush, hunting kangaroos and hooking fish. It was not a fully formed vision, but a path to my future was materialising – from that point on I wanted to learn as much as I could about life in the past.

Dubbo, in Wiradjuri country, may not seem like an ideal place to nurture a love for history – the local museum at the time was little more than an eclectic mix of farm machinery and other rural relics – but there was enough to fire the imagination. The school took us to Terramungamine, an assembly of over 100 axe and spear-grinding grooves on rock platforms by the Macquarie River. And my grandparents talked about Alec Riley, an old Aboriginal man who had worked for the police as a tracker and was much respected in town. What was a tracker I wondered? Finding an answer to that question was to take me thirty years.

Jump forward two decades and I’m embarking on a professional career in history. After completing a PhD in Aboriginal history (where I investigated the working lives of 19th century Aboriginal people on Alexander Berry’s Coolangatta Estate by the mouth of the Shoalhaven River), I’ve fortunately picked up a job writing history reports for native title claims. The work is fascinating. I’m required to collect as much documentary evidence as I can to tell a story about Aboriginal life in colonial times and form an opinion about the strength of their ongoing traditional connection. It is often thought that Aboriginal people were written out of the past, but scratch beneath the surface of the colonial archive and their lives, often tragic, emerge into the light.

One of the first claims I worked on took me back to Dubbo. The local Tubba-Gah Wiradjuri people had lodged a claim over nearby Goonoo, a vast cypress pine forest. It was eye-opening to learn about the lives of their ancestors who had fought hard for almost 200 years to keep a foothold on their traditional lands. These were stories untaught at local schools, but kept by the Tubba-Gah themselves and hidden in archives from Dubbo to Sydney. I learned of Tommy Taylor, the oldest-known of the Tubba-Gah ancestors, who escaped from the police in the 1850s and returned to raise a family on the outskirts of town. And I learned more about Alec Riley, who came from further west but married Tommy’s daughter Ethel Taylor and began working for the police just before WWI, drawing on traditional bush skills to track people lost in the bush and pursue criminals across the landscape.

As my career in native title continued, I was encouraged by my boss Ken Lum to pursue other research projects. It did not take long for me to settle on the history of trackers and I dived into the archive to find out more. I soon came across the police salary register, an official document recording the names and pay-scales of NSW Police employees. From 1862 (when the current NSW Police Force was formed), the register included trackers. Some names jumped off the page – Billy Dargin, the tracker who shot Ben Hall, was near the top of the list. But others remained mysterious and defied all attempts to find out more. I drew on my community connections to delve deeper into tracker oral history and it soon became apparent that over 1,000 Aboriginal men and women were employed by the police at almost 200 hundred stations between 1862 and 1973 when the last tracker retired. And the jobs they performed were varied, not just finding the lost and arresting the wayward, but training and looking after police horses, tracking mobs of stolen sheep cattle and, grimly, retrieving bodies from rivers and lakes. Trackers used not just traditional skills but those learned in the pastoral industry to forge careers that sometimes lasted half a century.

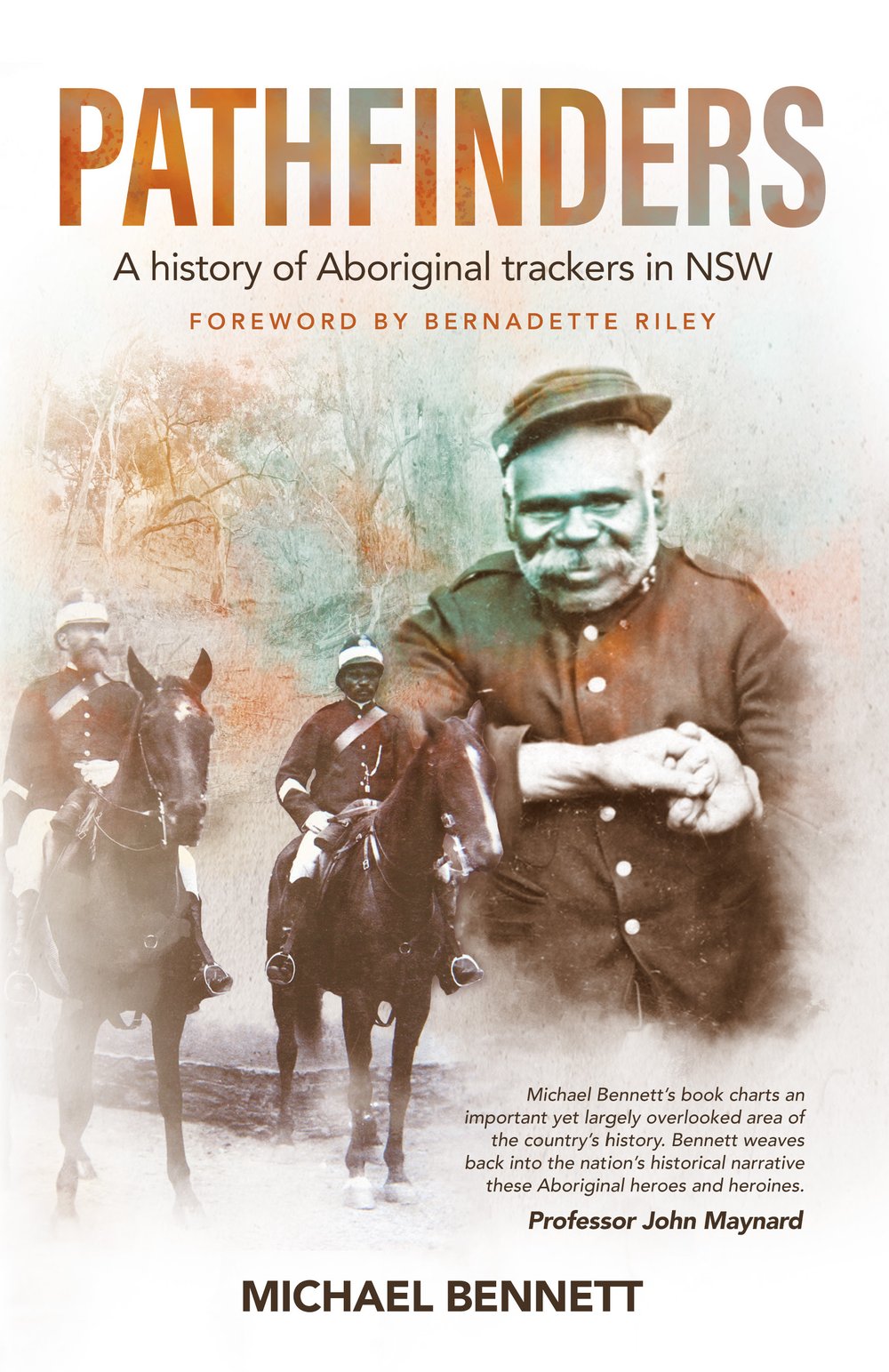

I was disappointed but not surprised that trackers had not received the recognition they deserved. Countless people owe their lives and wealth to trackers and it was obvious to me that now was the time for recognition to be given. Thankfully, NSW Police supported my project and with funding from NSW Heritage, the Pathfinders website was developed. But there was more to the story and with community encouragement I set out to write Pathfinders. I hope it communicates my passion for history and shows that Aboriginal stories of struggle and triumph are not hard to find if you care to look.

Michael Bennett's book Pathfinders: A history of Aboriginal trackers in NSW will be published by NewSouth in March 2020.