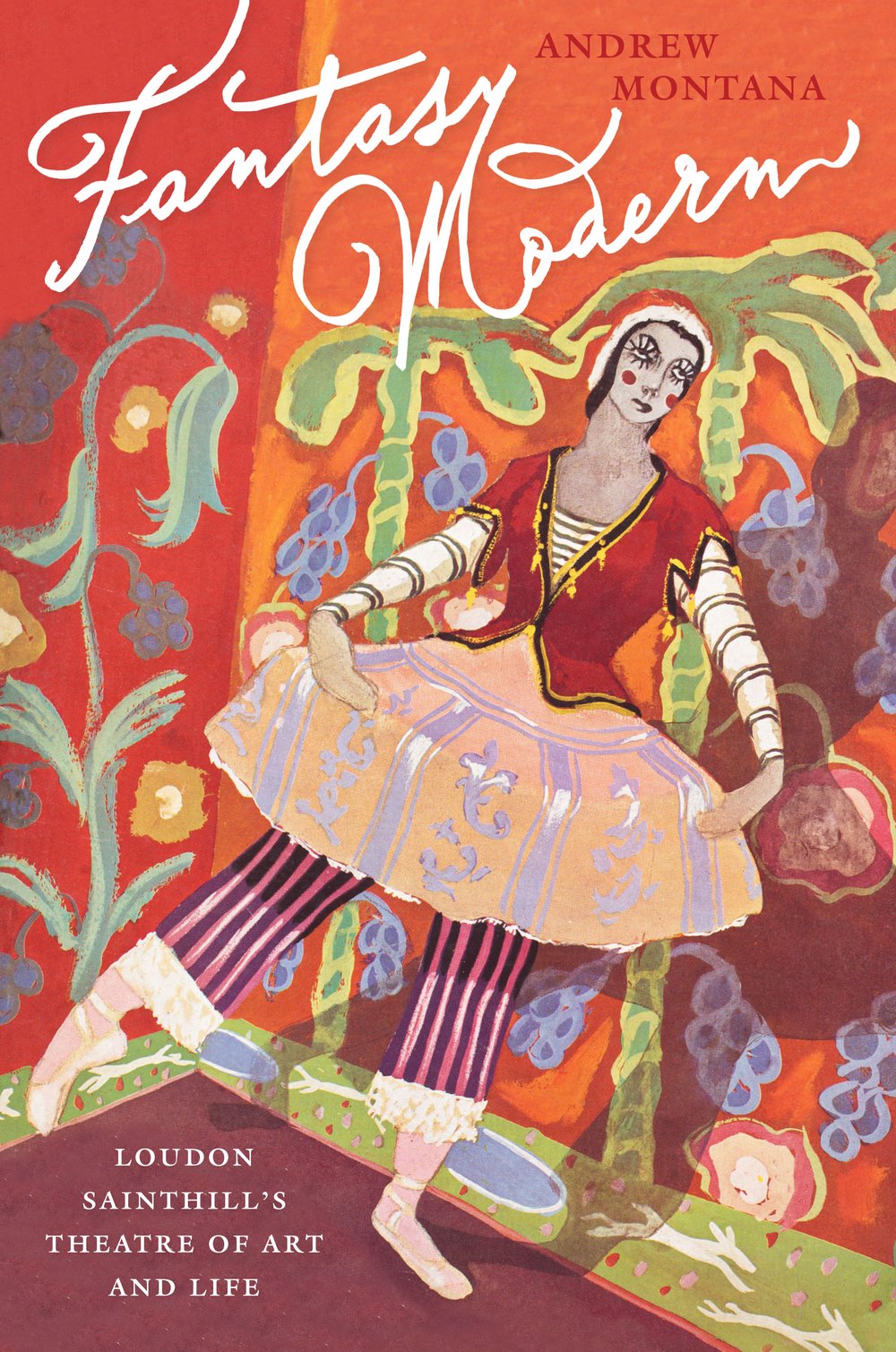

Actor and theatre director John Bell spoke of how vital Loudon Sainthill's work was in his own artistic journey, in this speech delivered at the launch of Fantasy Modern: Loudon Sainthill’s theatre of art and life, available now from NewSouth.

I feel a very personal connection with this book, because to a large extent it was Loudon Sainthill who got me excited about theatre.

When I was a teenager I didn't realise that Sainthill was, like myself, a small-town boy. He was born in Hobart (small enough in 1918) and I grew up in Maitland, which was, in the 1950's, rather culturally bereft. At school we had no art, no drama, no music; but I did have two wonderful English teachers who inspired in me a love of theatre, especially Shakespeare, and encouraged me to perform.

Hungry for information about the theatre, I scoured the thinly stocked shelves of the Maitland City Library; and luckily there were a couple of books with photographs of productions at the Old Vic and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon – the precursor to today's R.S.C.

The most astonishing and exotic designs in those books were by Loudon Sainthill, especially his Richard II with Paul Scofield, his Tempest with Michael Redgrave and his Othello with Paul Robeson. (Many years later I played Richard II in Manchester. The costumes were all hired in, and I was thrilled to find myself wearing that same costume worn by Paul Scofield, and designed by Loudon Sainthill.)

So as a teenager in Maitland I pored over those books of photographs for hours on end, and to me, Sainthill's designs became the essence of what theatre and Shakespeare were all about. They were exotic, wildly imaginative, extravagant and sensual and, what's more, the man could draw – a facility not universal among theatre designers.

Last year I gave a project to a young designer and he came back to me with a portfolio of costume designs that had all been photoshopped on a computer then made, digitally, into collages. They were witty enough but there was no indication of how they were to be made, or of what.

'These look interesting,' I said, 'When do I get to see the drawings?' He looked at me with a baffled expression and said, 'I don't own a pencil!'

Just a few years back a designer had to know what fabrics should be used, how they behaved and how you would construct a hat, jacket or a pair of shoes.

They would also present you with a model box – a sort of toy theatre with an accurate scale model of the set, so that you could plot your staging, entrances and exits with little figurines and experiment with lighting.

Now it seems model boxes are too expensive to build, so all you get is a computer image (hopefully a 3-dimensional one); but even the lighting is done virtually, via computer. Some of the fun and romance has gone out of planning a production as technology has taken over.

In 1948 the Old Vic made an historic tour of Australia with the Oliviers in Richard III, School for Scandal and The Skin of Our Teeth. I was only eight at the time so took no notice, but years later I came across the memorial programme of the tour, designed by Loudon Sainthill and edited by his lifelong partner, Harry Tatlock Miller. How I pined then, and wished I had been old enough to see those productions!

In 1955 the Old Vic toured Australia again, this time with Robert Helpmann and Katharine Hepburn in Measure for Measure, Taming of the Shrew and The Merchant of Venice, the last designed by Loudon Sainthill. Again I couldn't get to see the shows but I cut the coloured photographs out of my grandmother's Women's Weekly – pictures of Hepburn as Portia and Helpmann as Shylock – both dressed in Sainthill's typically exotic costumes. You could pick which one was Helpmann because he was wearing more jewellery and blue eye-shadow.

That reminds me of a story about Helpmann after he returned to Australia in the 1970's: He was asked to perform in some sort of Gala at the Sydney Cricket Ground. The only dressing room available was the umpires' changing room which had just a little table and chair and a naked light bulb high up on the ceiling. When the stage manager came around to give the call for beginners, he found Helpmann standing on the chair on top of the table, close to the light bulb, applying the blue eye-shadow. He asked, 'Sir Robert, are you alright?' Helpmann replied, 'I'm alright ... I don't know how those poor umpires manage!'

Loudon died in 1969 and in 1976 his lifelong partner, Harry Tatlock Miller, came back to Australia with the idea of setting up a scholarship for young designers in Loudon's name.

This book is as much a tribute to Harry as it is to Loudon. Loudon was the shy and retiring type; Harry, the entrepreneur and life of the party. He was devoted to Loudon and determined that his legacy would endure.

He gathered together James Fairfax, James Mollison and myself to act as the judging committee and award the scholarship, the first one going to Anna French. Anna had never been outside Australia, so she was thrilled to be met by Harry in London, shown over his Redfern Gallery in Cork Street, taken to dinner then driven home via Buckingham Palace and No.10, Downing Street. She was overcome. Harry was always the most gregarious and generous host, but certainly still grieving for Loudon when I met him here in 1976.

Andrew Montana's biography of Loudon, Fantasy Modern, is a detailed and insightful evocation of an artist and his era, and puts his astonishing work into context. Recognition of Loudon Sainthill here in his homeland is long overdue and is well-served by this sumptuous volume, lavishly illustrated.

It painfully recalls the deep frustration of generations of Australian artists, ignored, mocked and despised in their own country, who had to travel to England to achieve recognition and personal respect. It also depicts the artistic dilemma of trying to define a national identity in a country that refused to take art seriously; the paradox of trying to create a national theatre, but one based on an English model and aesthetic. On the other hand, there was also a profound parochialism and meanness of spirit reflected, for instance, in the move by Actors' Equity to ban the Old Vic playing at the Tivoli in 1948, on the grounds that it was taking jobs away from Australian actors.

Our cultural cringe was balanced by a dog-in-the-manger attitude to outsiders.

Thus it was that many of our greatest artists suffered a self-imposed exile and produced their best work in London. But their influence filtered back to affect profound changes here in Australia, and Loudon Sainthill's exotic and magical style is reflected in the work of designers like Kristian Fredrikson, Kenneth Rowell and John Truscott.

That school of design (fantastical, exotic, magical) has temporarily fallen out of favour; the current aesthetic in theatre is all about glass boxes and plain white walls. But the Sainthill vision of design will revive and manifest itself in a new generation of designers eager to satisfy an audience hungry for colour, daring, fantasy and display – whether we see it in theatre, opera, ballet, cinema or internet games – I'm sure that Loudon Sainthills influence will be felt for a long time to come.

Andrew Montana's book gives the man and his work the recognition they deserve. It will inform young designers of their heritage, fill them with respect for our pioneers and inspire them to contribute to our own great tradition.