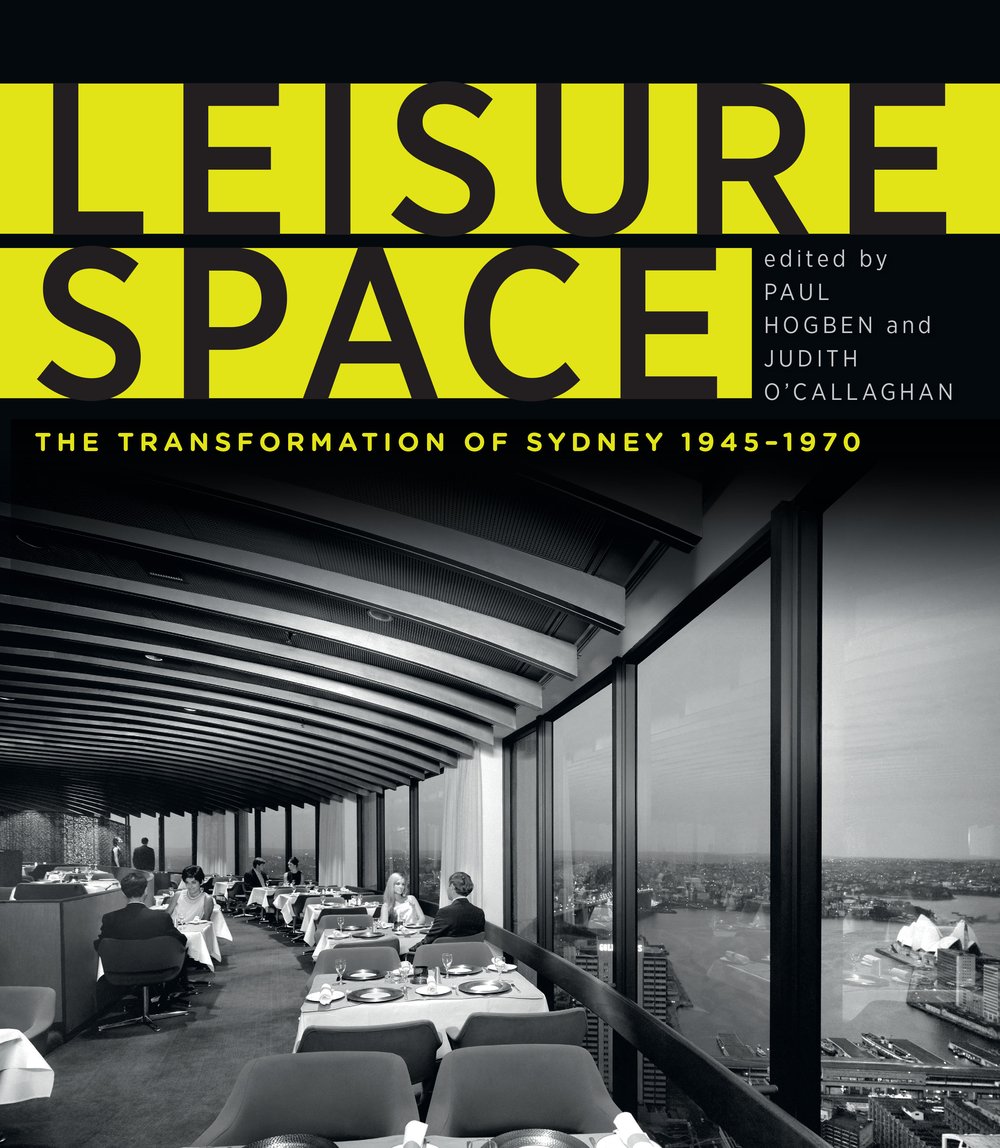

Spaces of leisure and pleasure, which were products of commercial and private enterprise, appeared in Sydney during the decades of 'the long boom', dramatically transforming the landscape from 1945 to 1970.

Sometime in early 1969 Sydney photographer Max Dupain ventured up to the rooftop of the new Travelodge motel near Sydney’s Wynyard Park to inspect the scene and contemplate the best position from which to capture the splendour of the building’s terrace roofscape. Looking across the pool his gaze would have been drawn to the skyline beyond and the looming brilliance of the Australia Square tower in the near distance, one of his favoured architectural subjects; the photographer perhaps struck by this scene of modernist synchronicity.

The stepped terrace and frames of the Travelodge rooftop offered a perfect viewing platform from which to look across to the tower and admire its imposing profile. The bathers in Dupain’s photograph of the Travelodge, however, do not seem concerned with looking out to the city but rather gratified by the casual enjoyment of testing the water and relaxing poolside, nonchalant about the spectacle that lay beyond.

The new Wynyard Travelodge, designed by H Stossel & Associates, was the largest to date at 27 levels, 15 of which contained the latest in motel room accommodation. A restaurant, located on the floor below the motel’s rooftop, offered patrons another elevated view of the city.

Dupain’s photograph captures a scene of exclusive leisure within a modern space of openness and abstraction, of elevation and elemental enjoyment. Locating a pool on the rooftop of a tall building was a technical feat new to Sydney, and indeed Australia, in the late 1960s. Swimming pools became a major scenic feature of luxury resort hotels in the 1920s, the Biltmore at Coral Gables in Florida boasting the largest. When it opened in 1953, the Beverly Hilton in Los Angeles had an elevated pool at its first floor level onto which guests could gaze from their rooms and the hotel’s restaurants. At the Wynyard Travelodge, the pool was shot skyward and, unlike the landscapes of greater Miami or Los Angeles, the emphasis was on being in and of the city, distinguished by the spectacle of elevation.

Dupain’s image wonderfully evokes the central theme of this book: the spaces of leisure and pleasure that appeared in Sydney during the decades of ‘the long boom’ and which were products of commercial and private enterprise. Collectively, the chapters serve to illuminate the role played by these spaces in the dramatic transformation of Sydney during the period 1945 to 1970.

By the late 1960s, Sydney was alive with hip and fashionable venues. It boasted three large international standard hotels, a collection of urban motels and boutique townhouses, classy cocktail bars and nightclubs, and a host of fine dining restaurants, all within about a mile’s radius of the city centre. These were not the older, principally internalised places of pre-war times, but new spaces that embodied modern design languages. They were part of the ‘new Sydney’, manifestations of the pleasure-seeking made possible through the powerful combination of greater amounts of free time and disposable income. They celebrated the visibility of wealth and prosperity and of youth seeking the means to express itself.

Although the book is focussed on the decades following the end of World War II, it recognises that leisure spaces continue to play a significant role in the way Sydney is defined and constructed. The health of the tourism, entertainment and hospitality industries is critical to the economic health of the city. After a lull in the years following the Sydney 2000 Summer Olympics, visitor numbers have risen again. In the year ending in March 2013, about 30 million people visited Sydney for overnight and day trips, spending $13.3 billion. In an effort to improve on these numbers, the NSW Government has committed to large leisure and entertainment-based projects on the western edge of the city centre, in partnership with private industry. Underlying these developments is the idea of primary catalysts, such as hotels and casinos, as a means of improving Sydney’s international profile and drawing visitors to the city. This idea is not new, the campaign mounted in the 1950s for the construction of first-class hotels in Sydney as a way of attracting tourists being an obvious example. By focussing on the decades of the 1950s and 1960s this book provides, for the first time, a cross-section of the leisure environments of this important period in the history of Sydney, and in doing so allows us to see present-day concerns in a broader context of cultural change, transformation and repetition.

This is an edited excerpt from the Introduction to Leisure Space: The Transformation of Sydney, 1945–1970 edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O'Callaghan, out now from UNSW Press.