Naming a book may seem more difficult than writing it. My first stab at a title for this memoir was Glass Negatives. I chose this because my father used glass negatives in a large ancient camera to photograph weekend picnickers he took up the Lane Cove River in a launch he drove for most of his working life.

Glass Negatives was complicated and nostalgic. My wife Gail Pearson suggested Optimistic Lives. This became the working title for most of the five years I worked on this book.

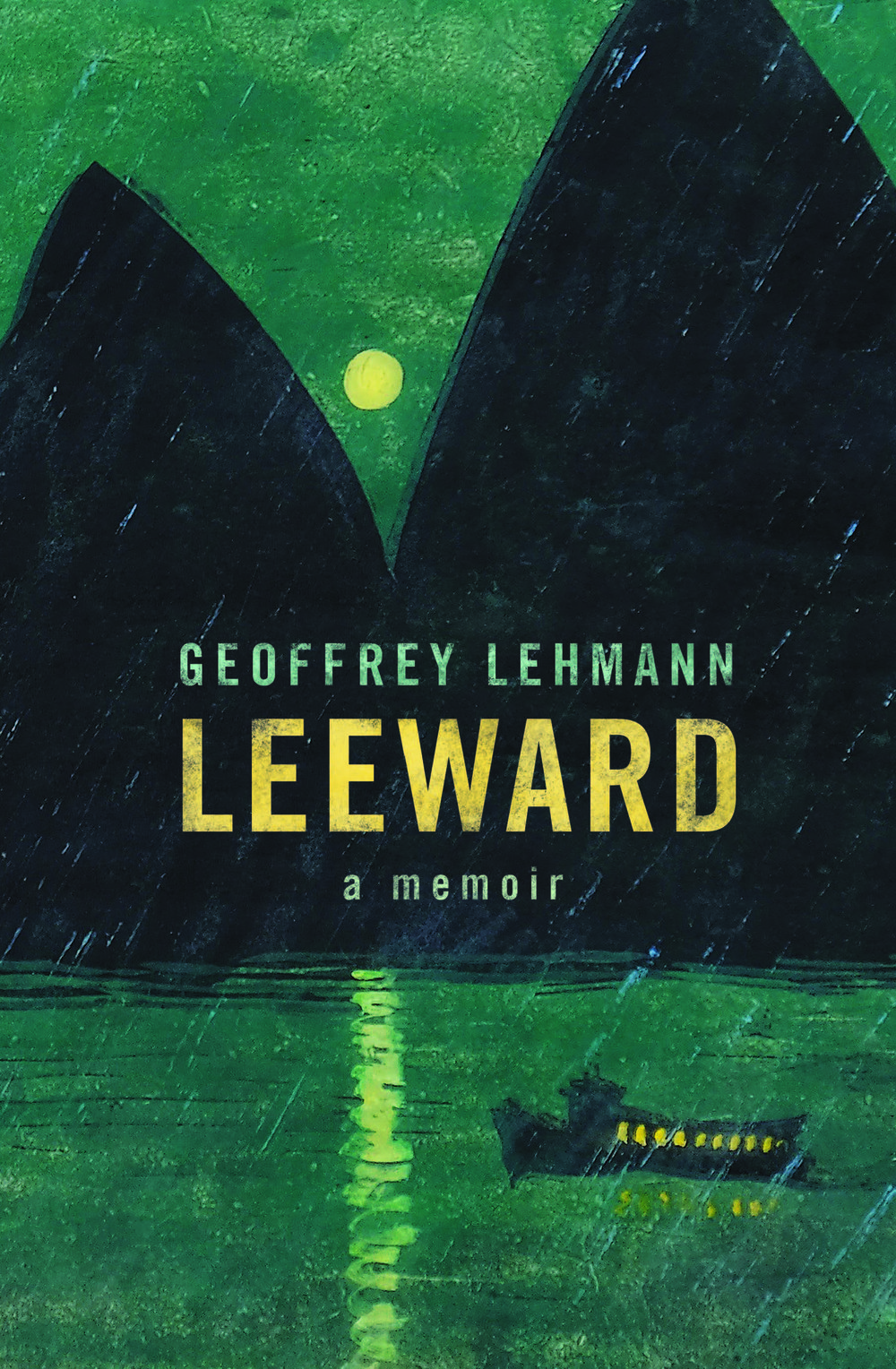

Then shortly before publication my publisher at NewSouth, Philippa McGuinness, suggested Leeward. Leeward was the weatherboard house at the head of Lavender Bay where I spent my first six or so months. It was obviously the right title. But the obvious is not always obvious.

In a recent New Yorker, 84 year old Janet Malcolm has an article accompanied by photographs of family members and her younger self which she discusses. She adds she does not wish to make a ‘recitation of my wounded child’s grievances’.

Her prose is elegantly elegiac. The photographs are allowed to speak, but not the wounded child. Malcolm’s is a safe sort of memoir, where the past is an artefact, selectively preserved and curated.

There is a second type of memoir you can write: something messy where everything hangs out, you recite your wounded child’s grievances and you argue with family ghosts. This is an unsafe sort of memoir, and one you may live to regret.

My father was brought up by a widow as one of five children. His father, who was a German carpenter, built the first Anglican mission station in New Guinea, caught malaria and died the day after he got back to Sydney in 1891.

My mother was also one of five children. Her father was a medico and, at the age of 10, one morning she went into his bedroom and found he was dead. He had died of a morphine overdose. This happened in 1906.

My parents married late in life in 1935: an ill-assorted couple, she nervous and bookish, and he working class and cautious. A year later my sister was born with a hormonal imbalance: congenital adrenal hyperplasia. (She had two recessive genes for this, and I have only one.) After surgical operations as a child, it became a great family secret, not fully explained to me until age 30, and it marred the rest of her life.

I was born in 1940, an unexpected late child. My father was then 48 and my mother was just two weeks short of 44. Until the age of 10 I slept in my parents’ bedroom, something I hated. But my sister was jealous about this – she slept in her own bedroom.

I never saw my parents express spontaneous affection for each other. They were shaped by the events of their childhood, and in turn they shaped me. So when I started writing it, Leeward had to be the second type of memoir, an unsafe memoir, in which the wounded child recites his grievances.

BUT, I had the working title Optimistic Lives, and I am an optimist. Although my parents had thwarted lives, and thwarted each other, I believe they were happy in their own strange way.

And I had a happy if rather strange childhood. Until the age of 10 I grew up in a skinny house built in the 1850s, which stood on three quarters of an acre of waterfront in McMahons Point. It had sandstone cobwebbed cellars which my father had filled with old tools and building supplies. When we switched on the lights in these cellars, brown moths fluttered past, as big as small birds. Driftwood and coke, even the odd rockmelon or dead cat washed up on our beach.

There were other houses on this land which my father owned, and he rented out rooms. McMahons Point was then a slum suburb, which was looked down upon by the other boys at the Anglican private school where I was a pupil. But in my mind it was a paradise. I learned early to make up my own mind and this may be why I became a 10 year old atheist.

Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature shows that over time human lives are getting better. With each generation, there is less violence and we live longer. There is a simple reason for this. When life evolved, consciousness was an evolutionary advantage, and happier life forms outcompeted unhappy ones. So we are hard-wired to want happiness and improve our lives.

I had a happy childhood, but I became myself only in my late thirties, happy at last, writing poetry, a tax lawyer, in a second marriage and father of five children.

Geoffrey Lehmann's book Leeward: A Memoir was published by NewSouth in December 2018.