Broadcaster, writer and columnist Mike Carlton on Come the Revolution by Alex Mitchell, at Gleebooks, Sydney

It occurs to me that some of you might be approaching this book with some caution. And I can understand why. It’s another journalist’s memoir.

I’ve read a couple of these recently – the great and good of the media trade looking back in tranquility upon their brilliant careers and admiring what they saw. Navel gazing par excellence.

No names. But some of the stuff was a bit like chomping through one of those packet chocolate puddings you get at the supermarket – a lump of stodge and a sticky, congealed sauce at the bottom. Oscar Wilde described foxhunting as the unspeakable in pursuit of the inedible. A good many media memoirs are the unreadable in pursuit of the improbable.

Now I should declare an interest. Mitchell and I are old mates.

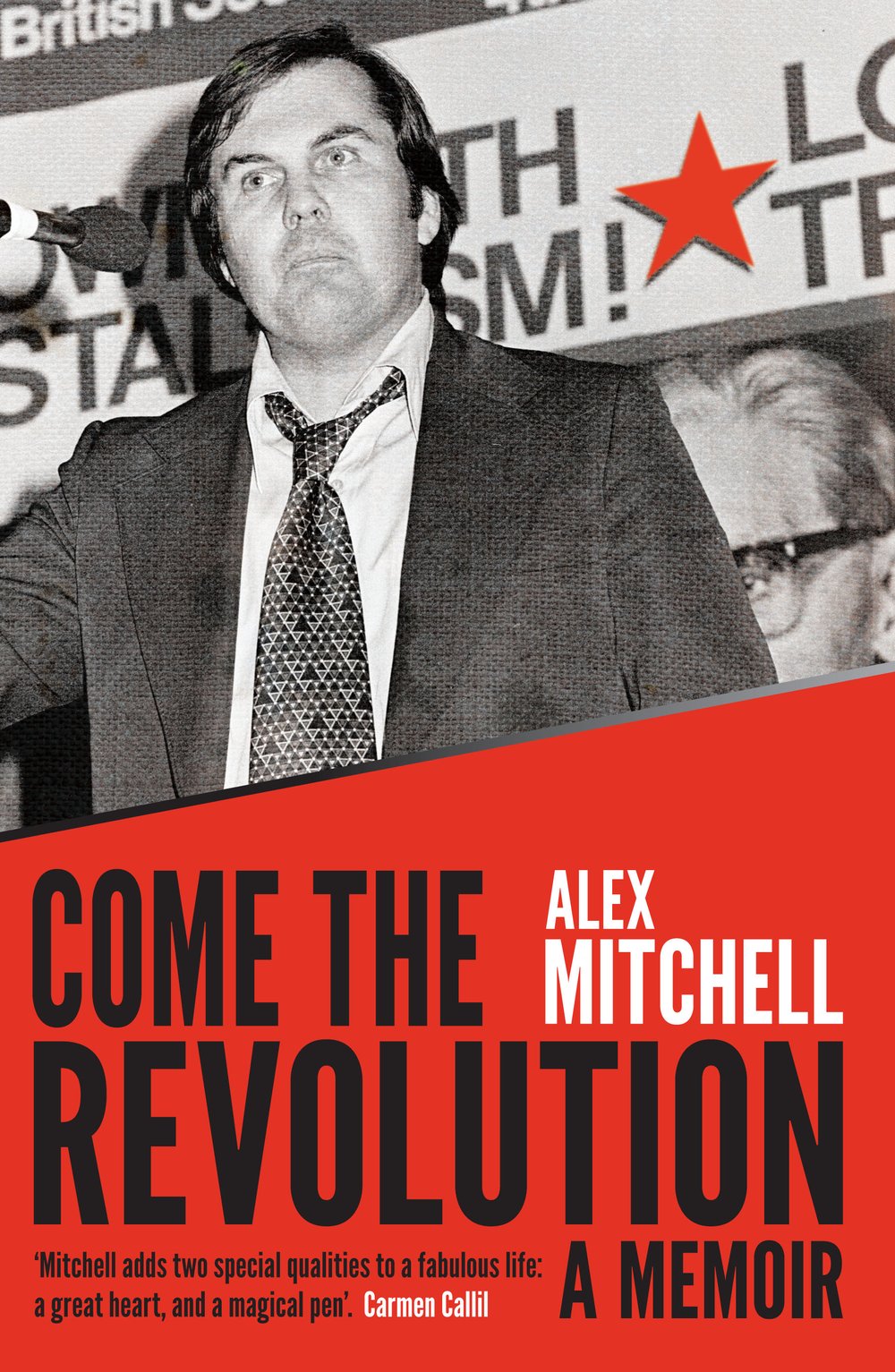

But I am here tonight to assure you, at the risk of my own reputation, that his book is very different. As indeed the title might suggest. Come the Revolution. A bold title, I think. No room for subtlety there. A grim tract, you might think, too.

But no. It crackles with wit and good humour. At times with piercing insight. But best of all, I think, it is illuminated by a self-deprecating scepticism – which I happen to believe is the mark of a good journalist. Alex never pretends to have all the answers. But, by God, he knows the questions.

Delightfully, he can tell a story against himself. Sometimes a hilarious one from, say, his first feeble days as a wet-behind-the-ears cub reporter in Mt Isa. Or the roaring days of the Sydney afternoon paper wars.

Sometimes a story of infinite horror … when as a young reporter, 26 years old, he was sent off to cover the Nigerian-Biafran Civil War.

Biafra is utterly forgotten now. A footnote in the unending catalogue of African tragedy. In the late 1960s, it was front page stuff. Perhaps 3 million people died from the war and the hunger and disease it brought about. Alex was so shattered by it, so confronted by his own very human impotence, that he could barely write about the atrocities he had seen. In that sense, he failed as a reporter. He admits it. Only now has he been able to put it down.

But the book is by no means all bleak. Far from it. It rocks along. Here was a young man on a mission to change the world. A country boy from Townsville. A red-ragging Trotskyite revolutionary working for Rupert Murdoch – which you don’t see a lot of these days. A seasoned and sceptical observer of Australian politics and society, state and federal.

And a good writer. He learned his craft well: tell ‘em what happened in the first paragraph, then give ‘em the adjectives. So many young journalists these days think they’re writing a novel: it was a fine and sunny morning when Joe Blow caught the bus to work. Only in the 7th paragraph do you find he was fatally Tasered by a police officer on Bondi beach.

Best of all, Alex thrived in that heyday, the high watermark of newspaper journalism of the 70s and 80s. An era, an epoch, if you like, that we will never see again. Roistering, rollicking tabloid journalism – exciting stuff then, but now of course, mired in the sewers of the News International phone hacking scandal.

And at the other extreme, he was part of some of the finest journalism that newspapers have produced. The great Insight team on London’s Sunday Times, which broke story after story – on the fine principle that one very good purpose of journalism is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

Alex was one of the exodus of young Australians who arrived in London in the 1960s and put a bomb under the complacency and hypocrisy of a society riven by class and ruled by a crumbling establishment of hereditary privilege and stolen wealth. The shockwaves reverberated back to this country … which was then run along much the same lines.

The thing I like best about Alex and, indeed, this book – is that he hasn’t given up. So many of our peers who were journalistic firebrands at the barricades of the 60s and 70s became, in their later years, craven reactionaries of the right. Discovering where their bread was buttered, they wolfed it down.

The late Paddy McGuinness springs to mind here – a volatile anarchist in his salad days – he, like so many of his ilk, subsided into a fat and fawning, claret-pickled caricature of the Tory plutocrats who signed his paycheques. Piers Akerman is another.

Not our Mitchell. Not our Alex.

If the fires of his youth are not still leaping to the sky, at least the coals are burning bright.