When I was a kid my mum used to say I’d either be very successful or end up in jail.

I feel sick. My hands are shaking and i’m queasy. I’m at a gala dinner for one of Australia’s richest men, the tough, no-nonsense Harry Triguboff, owner of the massive property development company Meriton. The grand ballroom of Sydney’s Sofitel hotel is packed with 500 of his family, friends and colleagues who have gathered to celebrate his eighty-first birthday. Rather than buying an expensive gift for the multibillionaire, the guests are here to raise money for the Bondi Yeshiva Centre, an organisation close to Triguboff’s heart.

As its general manager I’m here to speak about Our Big Kitchen, a community kosher and halal certified industrial kitchen that occupies the basement of the Yeshiva Centre. I have been in this role for 18 months.

In my previous life as managing director of The Satellite Group, I was used to giving speeches. I’ve never shied away from the public eye. I enjoy connecting with an audience and making a pitch. Indeed, part of what made me successful was my ability to think on my feet, to display confidence even if I felt unsure, and to wine and dine the most famous of figures. Yet here I am, trembling as I wait in the wings.

As I take my place on the stage, I look at my 20-yearold daughter, Carly, sitting in the audience. Carly is a confident young woman who is studying to become a history and drama teacher. She has helped me put my speech together, and she knows how I’m feeling. Carly and I have worked hard to ensure the speech will capture the hearts and minds of the audience.

I know that they are here because of Harry rather than a deep commitment to the cause. But I need them to see beyond the surface of what we do and to understand that by donating to the Yeshiva Centre, they are doing more than supporting a specific part of the community. Their dollars will help people with disabilities, those suffering from cancer, families who were going through particularly difficult times financially. Everyone knows someone who needs a hand.

I take a deep breath. I’m quivering. I look at Carly and she smiles back reassuringly. I begin, and explain that ultimately OBK is all about second chances – second chances for people with disabilities who need to feel part of the community; second chances for the homeless by reskilling them with a barista training course; second chances for prisoners taking part in the Corrective Services work release program, a program available to less than one per cent of the jail population, which allows low-security inmates to take their first steps towards reintegration into society. I take another deep breath. I once again look at Carly. She keeps smiling.

I swallow. ‘Allow me to reintroduce myself: I am inmate number 378121.’

***

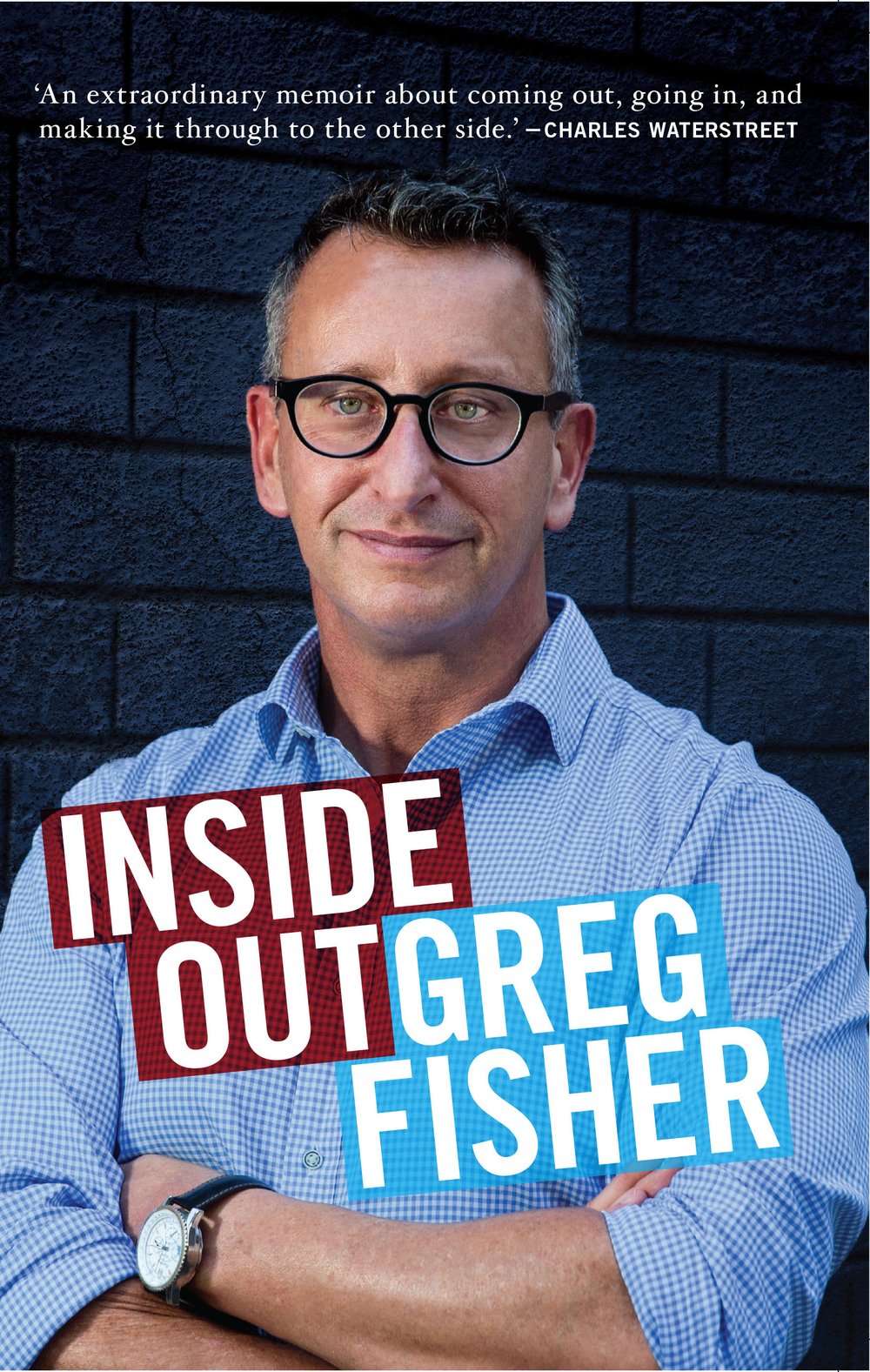

This is an extract fromInside Out by Greg Fisher, published by NewSouth in August 2015