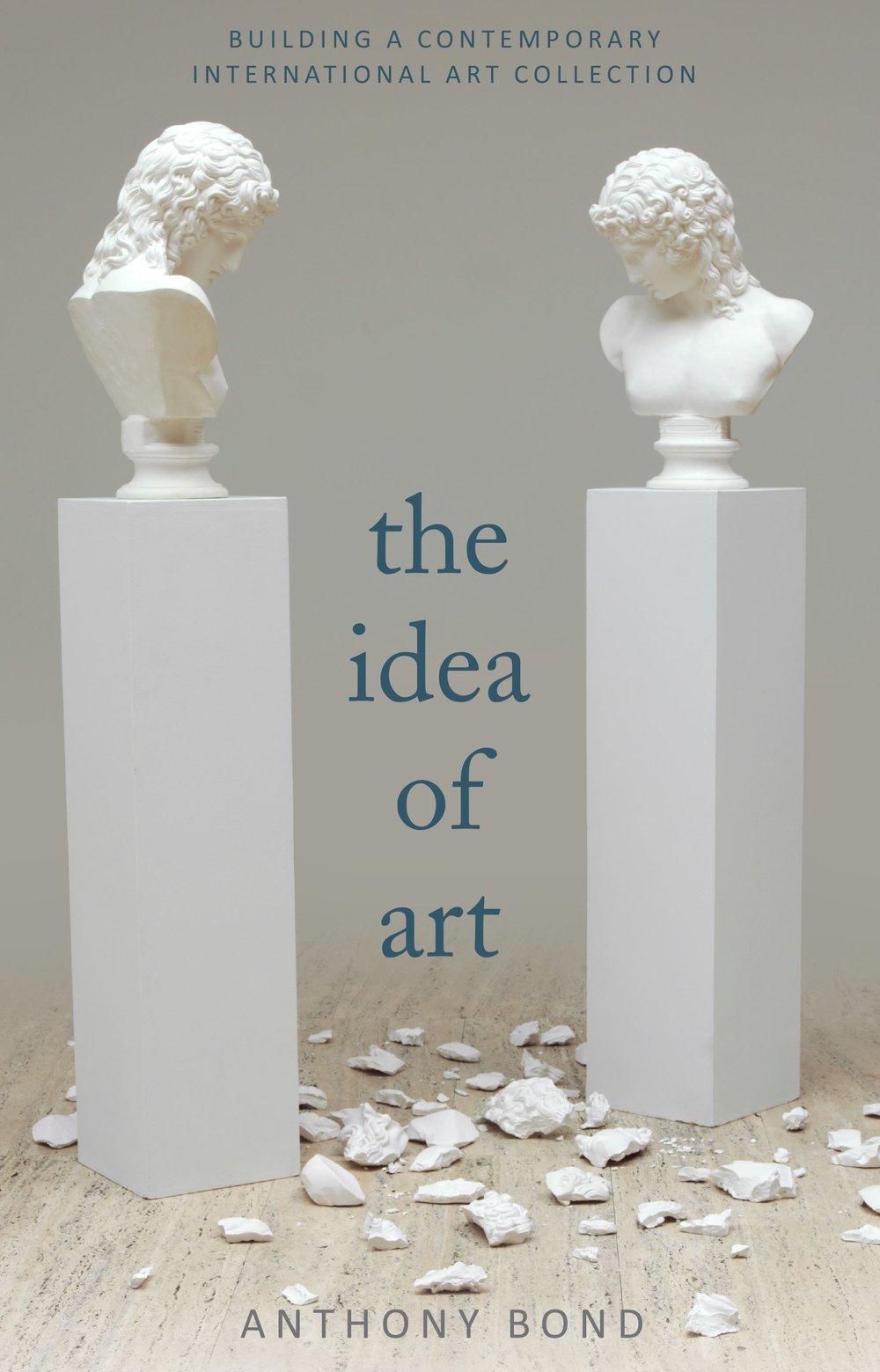

Anthony Bond was the first curator of contemporary international art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. His book The Idea of Art explores how he built the collection and, through interviews with some of the key artists in the collection, offers important insights into understanding and appreciating contemporary art.

‘Anthony Bond’s intimate knowledge of and friendship with artists and empathy with their processes gives his insight a particular richness and relevance.’ – Antony Gormley

In 1984, as a newly appointed curator, I was given the task of building a collection of international contemporary art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. I saw this as an unprecedented opportunity to assemble a coherent body of work that might represent the most powerful art of our time, a collection with a central idea unlike any other public collection of its kind in the world. It would even attempt to define why art still matters and to begin to rethink what art can be. It would not be a collection of everything done in the late twentieth century and beyond, but it would begin to map how a particular kind of art grapples with the fundamental problems of being and doing in human history from a contemporary point of view.

In the process of putting together the collection over twenty-nine years, certain artists were particularly influential, their ideas and work playing a large part in shaping and refining the collection and my interpretation of it. These artists, with many of whom I became lifelong friends, include the German painter Anselm Kiefer; the British sculptors Antony Gormley, Tony Cragg, Rachel Whiteread and Anish Kapoor; Colombian sculptor Doris Salcedo; British conceptual painter and sculptor Bob Law; American conceptualists Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner; British conceptual artist Stephen Willats; and Australian conceptual artist Ian Burn. Although this collection began as an international one I always included Australians whose art sat well within the conceptual framework of the collection, showing their work side by side with the best in the world, as it should be.

In 1990 Anthony Bond and Anish Kapoor (pictured) travelled to outback New South Wales, discovering a wild black hole in a gorge. Photo: Anthony Bond.

I believe the relationship between artist and viewer is the key to understanding the twentieth century avant-garde and much of current practice, whatever its medium. This notion of inclusion is central to the first wave of avant-garde art at the start of the twentieth century and was reasserted after the Second World War. Both manifestations rebelled against authority and hierarchical society. There was a shift away from the idea that feeling in art emanated from the artist’s internal world to an understanding of it as a moment of engagement between a viewer and an art object.

It also became normal that viewers should be considered active participants in the creation of meaning. Dada artists in the same period often took to the streets in protest and, like their post-war followers the Situationists in France, made banners, posters and graffiti. In post-war Europe, pop art, happenings, kinetic and cybernetic art were all discussed in terms of a return to the everyday and the emancipation of the viewer.

These ideas supported art that engaged with the real world and our experience of it. Sometimes this art could take the form of socio-political, philosophical or intrapersonal enquiry. Décollage, for example, is a French movement of the 1950s and 1960s that involved the selective stripping away of layers of paper from the accumulation of imagery on billboards. The physiological and optical effects of kinetic art in the same period involved the motion of the viewer’s body (as well as their eyes). It was a time when the history of visual representation was open to scrutiny.

This question of representation is linked to the enduring problem of understanding what we are as humans and how we visualise our being. An underlying preoccupation of philosophy – and for that matter of normal human curiosity – is to understand how consciousness relates to matter. Artists experience this every time they take some kind of matter – paint, clay, shoes, fat, felt, feathers, bags of spice, railway sleepers or a ball of string – and use it to make something they could never have known prior to materialising it. Mind engaging with matter manifests ideas that the mind alone cannot imagine. Art that explores these ideas became a focus of the gallery’s collecting.

In search of a location with a 360-degree landscape view for his Room for the great Australian desert (pictured left) in 1989, Anthony Bond took Antony Gormley (pictured right) to Mootwingie in far western New South Wales. Photos: Art Gallery of New South Wales (left)/Anthony Bond (right).

* * *

This is an edited extract from Anthony Bond’s introduction to The Idea of Art: Building an international contemporary art collection, published by NewSouth in association with the Art Gallery of New South Wales in August 2015. Find out more about Tony Bond at his website: www.anthonybond.com.au