I have been involved in criminal justice in one way or another for 50 years. In that time I have often been faced with very determined members of the public whose views about the criminal law differed from mine and I have spent much time in earnest discourse with them.

With that experience in mind, I met Rachael in Sydney’s Lindt Café in December 2012, nearly two years after retiring as DPP. She was sure she could help me write a book about the most important cases and challenges during my time as NSW’s Director of Public Prosecutions, even though to relive the experiences may be upsetting.

At her urging, I suggested a list of cases and challenged Rachael to draft a detailed description of one of them, using transcripts, judgments and other parts of the public record.

That first draft was the case of Jeffrey Gilham.

In late July 2000, I had to decide whether a young man named Jeffrey Gilham should be prosecuted for the killings that occurred in his family home at Woronora, south of Sydney, during the small hours of 28 August 1993. That night both of Jeffrey’s parents and his brother were stabbed to death. Jeffrey was the only member of his family to survive.

Jeffrey admitted that he killed his brother Christopher and pleaded guilty to his manslaughter, but said he did so after discovering that Christopher had murdered both of their parents. A huge cloud of suspicion still hung over Jeffrey’s head. To make matters worse, a lot of evidence that could have shed light on which brother was the murderer was either lost when the house was set on fire on the night of the killings or years later when police thought the matter had been closed.

I was satisfied that there was a reasonable prospect of conviction of Jeffrey. After his convictions in 2008 for the murder of both his parents, new evidence submitted on appeal in 2012 provided reasonable doubt about Jeffrey’s guilt. This new evidence didn’t prove Jeffrey was innocent, but it left open the reasonable possibility that his dead brother could have been the murderer. The court, having agreed that the new evidence raised reasonable doubt, had to give Jeffrey the benefit of the doubt and set him free.

The details of this case read like a horror movie, but that wasn’t the point of Rachael and I describing it in the book.

This contentious and unnerving case underlines how a prosecution can only go ahead if there is sufficient evidence to support a reasonable prospect of conviction. It also shows that the criminal justice system must give people the benefit of real doubt, even if that person scares us or still has a huge cloud of suspicion hanging over their head.

Jeffrey’s case is one of ten cases that has been described in detail in our book Frank & Fearless – the others include the prominent cases of Keli Lane, Gordon Wood, Michael Marslew, politicians, prosecutors and more. Just as with Jeffrey’s case, the point of spending years describing my list of cases, major events during my tenure and my hard-won insights is not to provide a collection of astonishing tales (although the facts of many of these cases are astonishing); rather, it is to illustrate key concepts of what it takes to hold a fair trial including: why the presumption of innocence is so important; why the accused must never be made to prove their innocence in a court of law; why proving guilt is a burden carried solely by the prosecutor; whether juries are reliable finders of fact (the answer is yes); how judges are stopped from being unfair (mostly by being required, unlike other public officials, to give detailed, written and public reasons for every judicial decision); and how difficult, even heartbreaking, it can be to ensure the same rules are applied to everyone, including people about whom we have strong feelings.

One very important feature of any fair trial is keeping politicians out and dealing with the media. Politics has no legitimate role whatsoever in any decisions as to who faces trial and for what and anything that rightfully happens within courtrooms, including decisions about what sentence an offender should receive. In my experience, there will always be some politicians who try to exert improper influence over the criminal justice system. They were never able to influence me inappropriately while I was DPP. The media also regularly criticised my decisions. But being popular is not in the DPP’s duty statement.

I also have much to say about the need for voluntary assisted dying laws, the futility of the ‘war on drugs’ and many other injustices all around us. One such injustice, the criminalisation of abortion in NSW, has been remedied since this book was written.

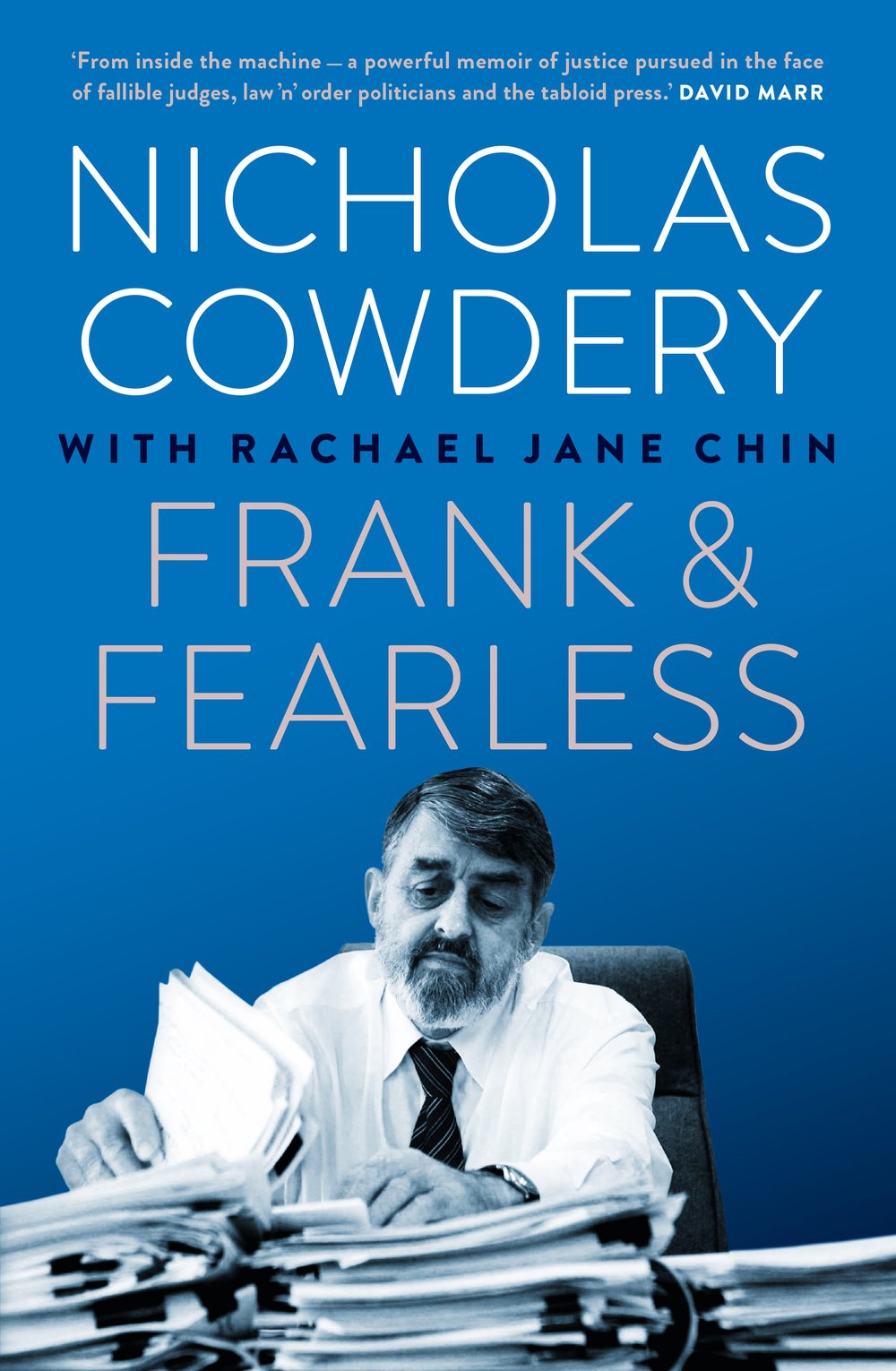

Frank & Fearless is my second book for the general public that includes discussion of the criminal law reforms I think our society urgently needs. But with Rachael’s assistance, it tells many stories.

Nicholas Cowdery's and Rachael Jane Chin's book Frank & Fearlesswill be published by NewSouth in November 2019.