It's a pretty good result when scientists can turn one species of animal into two, which was the case just a few days ago, when biologists separated the Lesula monkey from the owl-faced monkey in the Democratic Republic of Congo. But it's an even better result when scientists can extract no less than four new species from one known species.

Last week, a team of scientists reported the discovery of four new species of African bat, formerly assumed to be Hildebrandt's horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hildebrandtii), a species discovered in 1878 and named after its horseshoe-shaped noseleaf. Each one is just over 60 mm long and features a remarkable, very prominent noseleaf.

Noseleaves are incredibly complex outgrowths of skin and are common in bat species that echolocate (or emit sonar calls) through their noses. Noseleaves are thought to be involved in the shaping of an emission beam, sort of like an antenna. According to a 2007 study published in Physical Review E by scientists from Shandong University in China, different frequency sonar calls will be emitted from different parts of the noseleaf depending on what the bat's intentions are. For example, if it wants to navigate, a wide sonar beam that covers a lot of ground is the most appropriate, and this will be emitted from up to six sources in the noseleaf. On the other hand, if it wants to hunt, the bat will make a more compact beam by emitting through just two nostrils.

The newly discovered species of bat include Cohen's horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus cohenae) from the Mpumalanga Province of South Africa; the Mount Mabu horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus mabuensis) from Mt Mabu in northern Mozambique; Smithers' horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus smithersi) from Zimbabwe; and the Mozambican horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus mossambicus) from the Niassa Game Reserve of northern Mozambique. Not only do these bats increase our knowledge of the diversity of horseshoe bats, they also give us a wonderful insight into how evolution can necessitate adaptive shifts in body size.

The research team, led by Peter Taylor from the University of Venda in South Africa, distinguished the species from each other by DNA, frequency of echolocation (sonar), body and cranial size, and an analysis of the structure of their noseleaves. While analysing these different aspects to separate the species, Taylor and his team noticed that skull length has the most influential variable on the bats' peak sonar frequency, followed by the altitude at which they lived, followed by forearm length and noseleaf width. They found that skull length and altitude were also significantly correlated, which suggests that an old theory in biogeography called Island (or Bergmann's) Rule could be at play.

Island Rule states that the smaller and more insular an environment, the more larger species of animals will shrink, and the more smaller animals, such as rodents and bats, will grow. Based on their observations of the five bat species, Taylor and his team suggest that, through Island Rule, higher-altitude species such as the Mount Mabu horseshoe bat and Cohen's horseshoe bat, have a larger body size, and this looks to have an effect on the species’ peak echolocation frequency. 'We cannot exclude the possibility of altitude exerting an indirect negative influence on peak frequency through its positive correlation with skull size,' they reported in PLoS One.

And it mostly fits, with the 66 mm-long Cohen's horseshoe bat emitting the lowest recorded peak frequency (33.0 kHz) at an elevation of 690 metres, while the smaller 62.5 mm-long Hildebrandt's horseshoe bat emits a much higher peak frequency of 42 kHz at a 390 metre elevation. 'Altitude (<600 m or >600 m) alone explains 35.3% of variation, with populations from low elevations having much higher peak frequencies than high elevation populations', said the researchers.

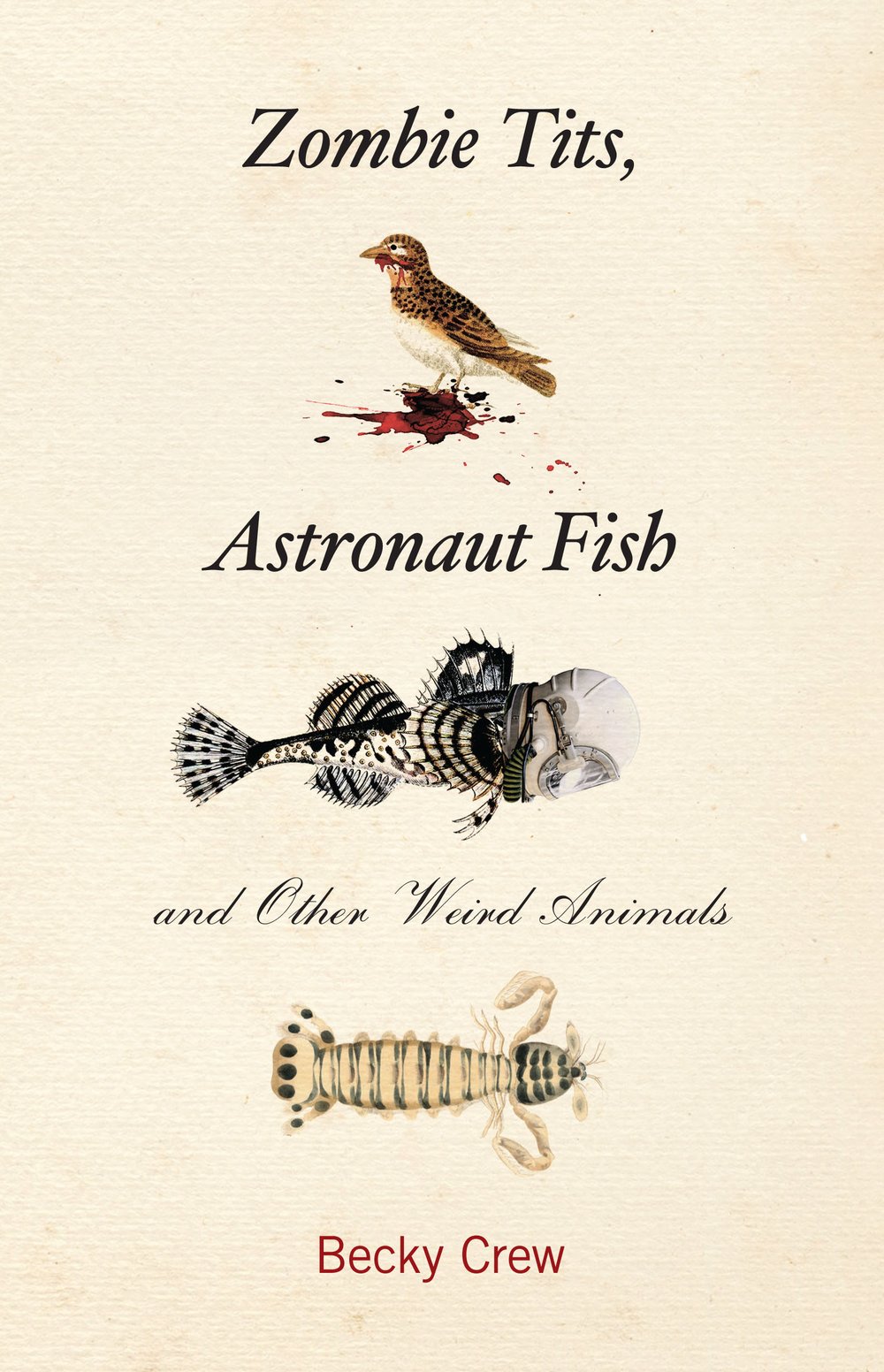

And speaking of Island Rule, last year it was suggested that a newly discovered extinct species of rabbit named Nuralagus Rex evolved to be a lazy, 12 kg giant because it was restricted to the tiny Greek island of Minorca. You can read about this so-called ‘King of the Rabbits’ in my new book, Zombie Tits, Astronaut Fish and Other Weird Animals, due out next month.