I have been writing about Australian soldiers of the Second World War for more than 30 years, and the figure of Tom ‘Diver’ Derrick VC DCM has loomed large throughout that time. My writings have covered a broad range of topics concerning those hundreds of thousands of men, but I mentioned ‘Diver’ in my first book, published in 1996, and in my eleventh, published in 2018, and in several in between. Anyone who tries to write about the Australian soldier in general will come across this famous infantryman – indeed during the war he appeared on the cover of a book about Australians in New Guinea entitled ‘Soldier Superb’. In many ways he embodies the archetypal Australian fighting soldier: a larrikin of humble origins, a sportsman whose strength and street-smarts helped him to earn high decorations on the battlefield and to rise through the ranks despite the prejudices of superior officers. Moreover, as I discovered in 1988 while researching in Canberra for my doctorate, the Australian War Memorial holds photocopies of the diaries he kept throughout the war. This allows readers to go directly into the mind of an Australian Achilles.

Another great Australian soldier of that war who kept a diary was Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop, whose record of his war, especially as a doctor among other prisoners of war on the Thai-Burma Railway, is a classic and a reflection of a second military archetype: the soldier who saves lives rather than takes them. Others in that line are Neville Howse, Australia’s first Victoria Cross winner and Jack Simpson, who used a donkey to rescue wounded men on Gallipoli.

While researching another book in 2018, I had the sudden thought that these diaries, of which I had transcripts, would make a wonderful topic for a book. Derrick was a member of the 9th Australian Division, a formation about which I have over the years developed a great deal of knowledge, and not a little love. I felt that I was well-positioned not only to reproduce these diaries but to comment on the hundreds of references to people, places and other elements of his service that readers would want to know more about.

Derrick’s diaries are less refined than Dunlop’s. They also reflect the behaviour of a man less concerned with others, at least at the start of his service. Gambling, drinking, stealing and fist-fighting figure in the early pages. But so does a vulnerability that brought out the sympathy of the schoolteacher in me. A turning point in his life came in February 1941 when a schoolteacher-turned-soldier, Lieutenant Drew McLay, taught him in a junior leaders’ school and made him feel he was ‘not altogether hopeless after all’. Ambition to rise through the ranks now became a driving factor in his military career. This reflects one of the most interesting elements of Derrick’s writings, namely that they show character development. His first campaign, in Tobruk in 1941, also taught him hard lessons about coping with fear and violent death, and in his next campaign, at Alamein in 1942, he was a veteran who won the second highest award for bravery available to men in the ranks. He described these events, as well as those that won him the Victoria Cross in New Guinea the following year. By that time he was a sergeant commanding a platoon of some 30 men. During his last campaign, in Tarakan in 1945, he was an officer, and his diary reflects the mind of a man much more responsible and focused on leadership than ever before.

Derrick’s service is not a simple ‘bad boy becomes a heroic man’ story, although that theme is present. Every person’s life contains mystery. This man’s life, though he documented it daily over long periods, still remains largely mysterious. There are gaps in his writing in every diary entry, leaving the reader wondering often ‘but what exactly did you do?’ or ‘what did you think about that?’ Still, it’s better than trying to reconstruct a life and its driving forces without the person’s own words, which historians so often do. And that reconstruction is really difficult when the life is shrouded in legend, as Derrick’s is. Nowadays, many people have no idea who Derrick was. But thousands do, and most have received understandings and opinions of what he did. As this book reveals, some of those understandings are incorrect or dubious. I’ve offered my own interpretation of Derrick in a lengthy introduction and at times in the notes to the diary entries. Regardless of whether those interpretations convince readers, they will also be able to read the unmediated words of one of Australia’s most famous combat soldiers, and to make up their own minds.

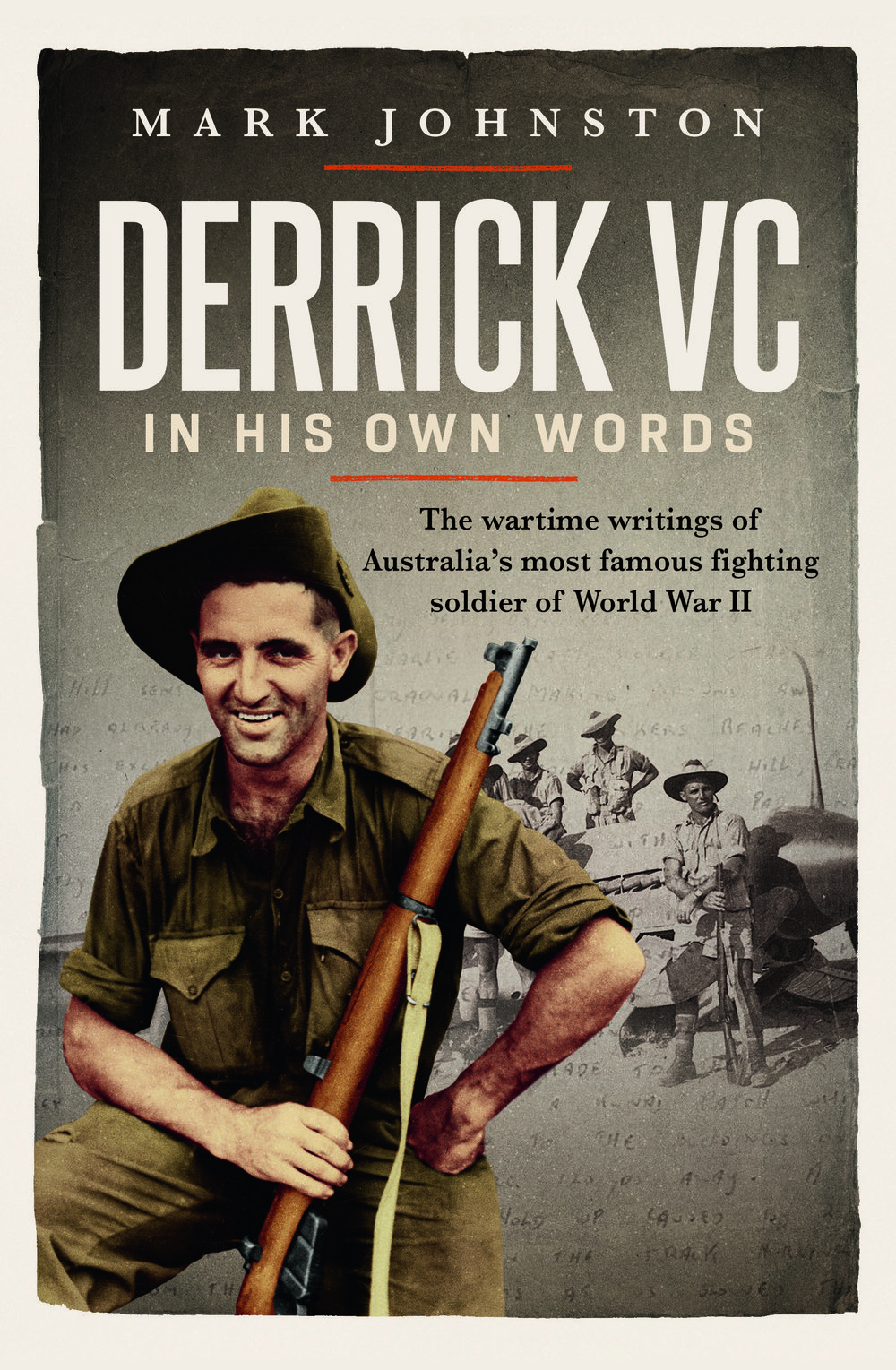

Mark Johnston's edited book Derrick VC in his own words: The wartime writings of Australia's most famous fighting soldier of World War II will be published by NewSouth in April 2021.