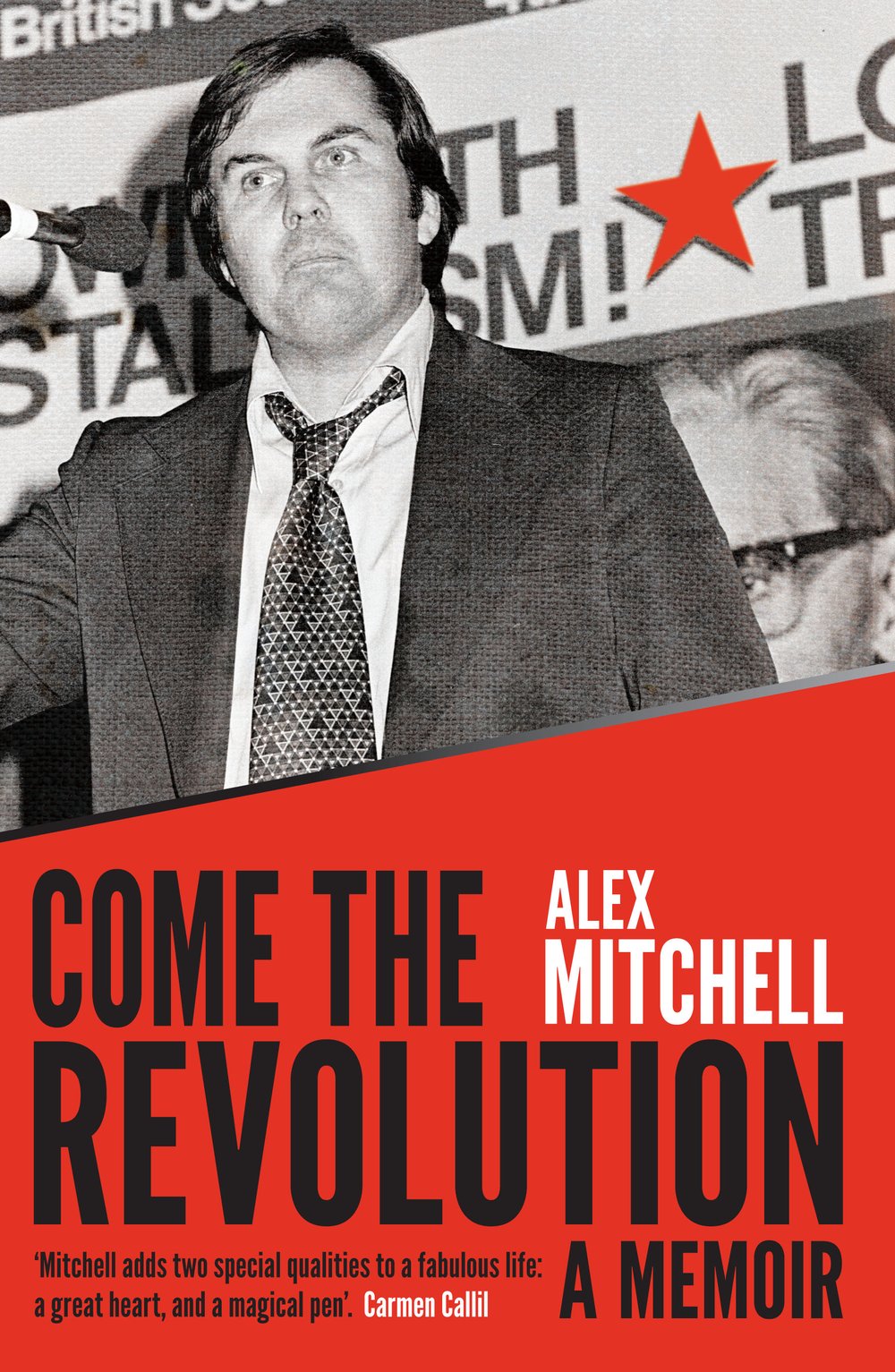

On 10 November Laurie Oakes launched Come the Revolution by Alex Mitchell, published by NewSouth, at NSW Parliament House. This is his launch speech.

Bob Hawke used to have a rule. He wouldn’t launch a book unless his name was in the index. That’s why the index to David Marr’s 1980 biography of Garfield Barwick has the following entry: Hawke, R.J., no mention of.

I regard the Hawke approach as eminently sensible, so the first thing I did when I got my hands on Come the Revolution was check the index. My name is there, so I’m here. But I have to say, the first reference I looked up caused me some distress.

It’s the story of how, when Alex and I shared a flat in Paddington in 1964, the legendary Mount Isa strike leader Pat Mackie turned up on our doorstep, and we had to first hide him from the rozzers and then smuggle him out under their noses so he could get back to Queensland with money he’d raised for the strike fund.

I’m quoted in the book as saying: “The Mackie episode was an eye-opener for me, but it was pretty much par for the course for Alex. I blame him and the Mackie incident for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation opening a file on me.”

The thing is ... after I said that a few years ago, I thought it would be interesting to see my ASIO file. So I applied for it, as you’re entitled to do after a certain period of time.

What I was sent was so disturbing that I find it difficult to talk about, even now.

It was a letter saying that there was NO ASIO file on me and never had been.

You can imagine the humiliation.

It’s not just the Mackie thing.

When Alex became a Trotskyist leader in Britain and was doing his utmost to bring about the workers’ revolution, I used to try to catch up with him for a feed or a drink whenever I passed through London.

And there always seemed to be a little man in an overcoat, hat pulled down, sitting in a dark corner, pretending not to watch us.

But still no security file. It doesn’t say much for MI5/ASIO liaison, does it?

Anyway, I’ll put my embarrassment to one side and take comfort from the knowledge that there’s not a security file on Alex, either. There’s a filing CABINET. And I deserve at least a tiny bit of credit for that.

Because, as he says in Come the Revolution, I gave him his introduction to the anti-Vietnam war movement on the university campuses, and put him in contact with people who wore duffle coats and sang doleful folk songs. It was an important part of his political journey. “The war,” he writes, “was the watershed of my life.”

This is, of course, a very political book. It deals with the author’s political development. It tells the story of a political movement – including the results of Alex’s own investigation of the murder of Leon Trotsky. It details the activities and ultimate destruction of a radical political party. And it contains a strong political message.

But it’s also a book about journalism. A terrific book about journalism, in fact. Josh Rosner, a teaching fellow in journalism and communications at Canberra University, who reviewed it in The Canberra Times, wrote that Come the Revolution would be required reading for his first-year journalism students in 2012.

And, I’m telling you, if it doesn’t get them fired up about the career path they’ve chosen, nothing will.

Here’s a bloke who started out at 14 getting printer's ink and glue smeared on his genitals at The Townsville Bulletin and went on to cover some of the most notorious murders in Sydney in the 1960s, was in Canberra when Sir Robert Menzies retired after 17 years as prime minister and asked the first question at Ming’s final press conference, moved to Fleet Street and became part of the Sunday Times 'Insight' team for several of its most famous investigations including the Kim Philby spy scandal, and made a ground-breaking TV documentary on Idi Amin that involved conning the dictator into an interview that helped to expose him for the monster he was.

They’re just the headlines of an illustrious journalistic career.

Two anecdotes from the book ...

When the documentary team was safely back in England after the Idi Amin interview, the cameraman was asked what had been the scariest moment in Uganda. He replied that it was when Amin was chatting to the producer while the camera and lights were being set up. “I saw out of the corner of my eye Alex grabbing documents from Amin’s desk and shoving them into his pocket,” the cameraman said. “I thought we’d never get out of there alive.”

And I love the question Alex asked at that final Menzies press conference. It’s so typically Mitchell – which is to say, it’s not the obvious question. “Sir Robert, you have told us about your achievements,” Alex said, after the retiring PM’s opening statement. “But what about the failures?” To which Menzies replied instantly: “There weren’t any.”

What Alex’s politics and journalism have in common is passion. A lot of us in the craft stand back, adhering to the view that journalists should maintain a certain detachment. Others shun the idea of detachment, and believe they should use journalism to try to change things for the better.

The attitude of detachment was not a comfortable fit for Alex. He felt too strongly about a whole lot of things for that. And eventually he lost faith in the ability of mainstream journalism to bring about the kind of changes he believed necessary. So – for 16 years – he opted for a more direct approach alongside people like Vanessa and Corin Redgrave in Gerry Healy’s Workers’ Revolutionary Party – editing its newspaper being one of his duties.

But when he returned to mainstream journalism (he’d call it capitalist journalism) and to Australia, in 1986, it was as though he’d never been away from either.

Come the Revolution got me excited about journalism all over again. As I read the description of the printing process at the old Townsville Bulletin I found the smell of hot metal that I loved so much when I first joined Sydney's Daily Mirror 47 years ago was back in my nostrils. I could hear the clatter of the linotype machines, the roar of the presses.

When I read the tips Alex got as a young journalist from old pros, it was déjà vu ... because some of the same old pros mentored me.

“Give them the facts and keep yourself out of it.” And: “Put just two or three facts in every sentence. No more. Otherwise the fuckers won’t know what the hell you’re writing about.” And: “Pretend that a reader is sitting in front of you on the other side of the typewriter and asking you the question, ‘What’s this story about?’”

And then there’s the way two great expat Australian investigative journalists – Phillip Knightley and Murray Sayle – taught Alex to look at ordinary, everyday reporting as Public Service Journalism when he first got to Fleet Street. They called it PSJ.

Alex writes: “PSJ is the staple diet of the reporting class ... It basically means telling the readers what is really going on, whether it is local, national or international news. PSJ is the sworn enemy of lazy rewrites of press releases and rescripted quotations from politicians and business leaders. To effectively conduct PSJ you need to be inquisitive, ask hard questions and go the extra distance in researching an article because that is your responsibility to the readers.”

Or, as Sayle once put it, according to Alex, “They don’t want bullshit; they want to know what’s going on”.

If every young journalist digested that, and if all reporters saw their job as a public service, the standard of reporting in this country would shoot up. And the decline in the public’s trust in journalists and journalism might be arrested.

The head of The Sunday Times 'Insight' team, another Australian, Bruce Page, didn’t think investigative journalism should be a special category. Alex quotes him as saying: “Every story must be tested for origin, bias and coherence, and the evidence behind it critically analysed. The stream of news only stays hygienic if the investigative process is continuously available.”

These were great people to learn from. They are the kind of lessons we might wish were put into practice more often in today’s journalism.

Alex left Australia bound for the UK on the P&O liner Oronsay immediately after the anti-Labor landslide in the 1966 Vietnam War election. This was partly because he was depressed about Australian politics. But love of journalism was still by far the bigger consideration for him.

He writes: “I had spent hours in the parliamentary library reading the British newspapers and was captivated by the quality of the writing and the scope and depth of the coverage.” He was drawn towards Fleet Street because it was the Mecca of world journalism.

And what he tells us in the book about his experiences there, the people he met and the stories he was involved in show why that was so.

I first met Alex when I joined the Daily Mirror straight out of Sydney University. We were pretty much the same age, but he’d been in journalism a few years by then — on the Townsville Bulletin and the Mount Isa Mail, before Rupert Murdoch brought him to Sydney. He was already a bit of a legend as a prankster and a player as well as a journalistic up-and-comer.

The flat Alex and I shared for a time was the bottom half of an old terrace house in Suffolk Street, Paddington, that we dubbed Suffolk Manor. When we first looked at the place, we found we couldn’t rake up the deposit between us so we repaired to the Journalists’ Club to drown our sorrows, and idly started putting coins through a poker machine.

Alex hit the jackpot, and quick as a flash we were back at the real estate office, signing the lease, and paying the deposit in coins as the agent explained that the owner of the property strongly disapproved of gambling and drinking. We, of course, assured him that we shared those sentiments.

A result of living with Alex for a while was that I saw the deeply serious side of him which, I think, was largely hidden from most of his colleagues at the time.

They would have been surprised when he was spotted taking part in an antiwar march. He writes, in fact, about being rebuked on the grounds that “Journos don’t go on marches – we report them”.

Sometimes, when liquor had been consumed at The Manor, a rare event of course, he would talk about things that made him angry. And he would tell some of the stories that are in Come the Revolution about the treatment of indigenous Australians in North Queensland, and the behaviour of police, and union bosses who sold out the workers.

So when he eventually cut short a brilliant career in the British media to throw in his lot with the Trots I was probably not as surprised as some who knew him.

What I didn’t understand until I read this book, though, was how Alex’s experiences as a journalist gradually shaped his politics. The injustices he saw, the things he learned, the people he met, pushed him in one direction.

Until he abandoned mainstream journalism altogether to become a political journalist, in the true sense, as editor of the Trotskyist newspaper The Workers’ Press, later renamed News Line.

As he explains it in the book: “It seemed to me that if you wanted to be taken seriously, then it was time to do something serious. There was little point in talking about socialism while selling your talent to Lord Thomson of Fleet or Lord Bernstein.”

The section of the book on Alex’s life as a Trot, like the stuff on journalism, is a rattling good read, with a cast of characters that includes Yasser Arafat and Muammar Gaddafi.

The plotting and intrigue inside the Workers’ Revolutionary Party puts the shenanigans of the Labor Party’s NSW Right in the shade.

It culminated in the leader, Gerry Healy, being framed in a sex scandal (Alex believes security agencies were involved), and his opponents flogging off everything in sight, including property on loan from Vanessa Redgrave, and taking off with the cash.

Alex covers the story in the book like the terrific journalist he is.

After the WRP imploded, he and his partner, Judith, boarded a plane for Australia—which was good news for journalism in this country.

As Alex puts it, he dismantled his previous political life and rebuilt his career in the mainstream media, writing about crime, corruption, cops – anything that fell into the category of Public Service Journalism – and eventually he became the Sydney Sun-Herald’s state political editor.

But if you think the political fire in Alex Mitchell’s belly has gone out, you could not be more wrong. "As capitalism repeats its failures," he says, "and the planet suffers more irreversible damage from corporate exploitation, people’s attitudes will change. Surely then the revolution will come."

And his final comment on journalism is sobering.

"I had worked both sides of the street and appreciated the advantages and disadvantages of the capitalist press and the socialist press," he says. "Neither are good places for freethinkers, democrats or individualists."

It’s now my pleasure to smash the champagne bottle across the bows of Come the Revolution ... and declare it launched.