Most of us are employed by businesses, derive our income from them, and spend a large part of our lives in offices, factories, farms and mines. The business world is the stage for our ambition, envy, disappointment and achievement. There is a part of our mind that is always ruminating on where we stand in the business in relation to our rivals, our bosses and our subordinates. Much of our contemporary language derives from business consultants, and our cultural characteristics are linked to the part of the business world we inhabit, from the bright, brittle confidence of the banker to the weary detachment of the IT engineer or the wariness of the typical CFO.

Our other lives are defined by the absence of business. When we are on vacation, we usually and very specifically mean that for a period of time we briefly suspend our business existence for one which is in important respects its opposite. As often as not we think of our family lives partly as a restoring refuge from our business lives. And where once the business world was confined to the world of privately owned and profit-making institutions, the culture of business management has so far permeated the rest of society that charities, hospitals, government instrumentalities and departments, even cabinets, churches and the courts, now take pride in a claim that they are run ‘like a business’. When the made man explains that a recent killing was ‘just business’, we get the joke.

For all that, however – and this is why this book is so welcome – this vast area of our lives is not well examined. There are not many good novels about business, only a few good films and one or two cable series. Compared with the police and hospitals, business is not often the scene for fictional drama, and compared with crime and sex hardly ever the theme – unless crime, sex and business are combined, as in The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Much of the most penetrating, thoughtful and illuminating writing in the literature of business is in journalism – in non-fictional accounts of success and failure in business, of corruption and deception, of how businesses are run, who runs them, and how the goals and purposes of businesses interestingly differ from the management textbooks. Some of the best of it is written with the urgency, force and impermanence of daily journalism, by reporters long trained in their craft and now possessing a wide knowledge of their subject and its players.

The pieces collected here by Andrew Cornell tell their own stories. They help to illuminate an important part of our experience. They inform and they also instruct. They remind of us the force of that customary boardroom adage, ‘Let’s not do anything we wouldn’t want to see on the front of the business pages.’

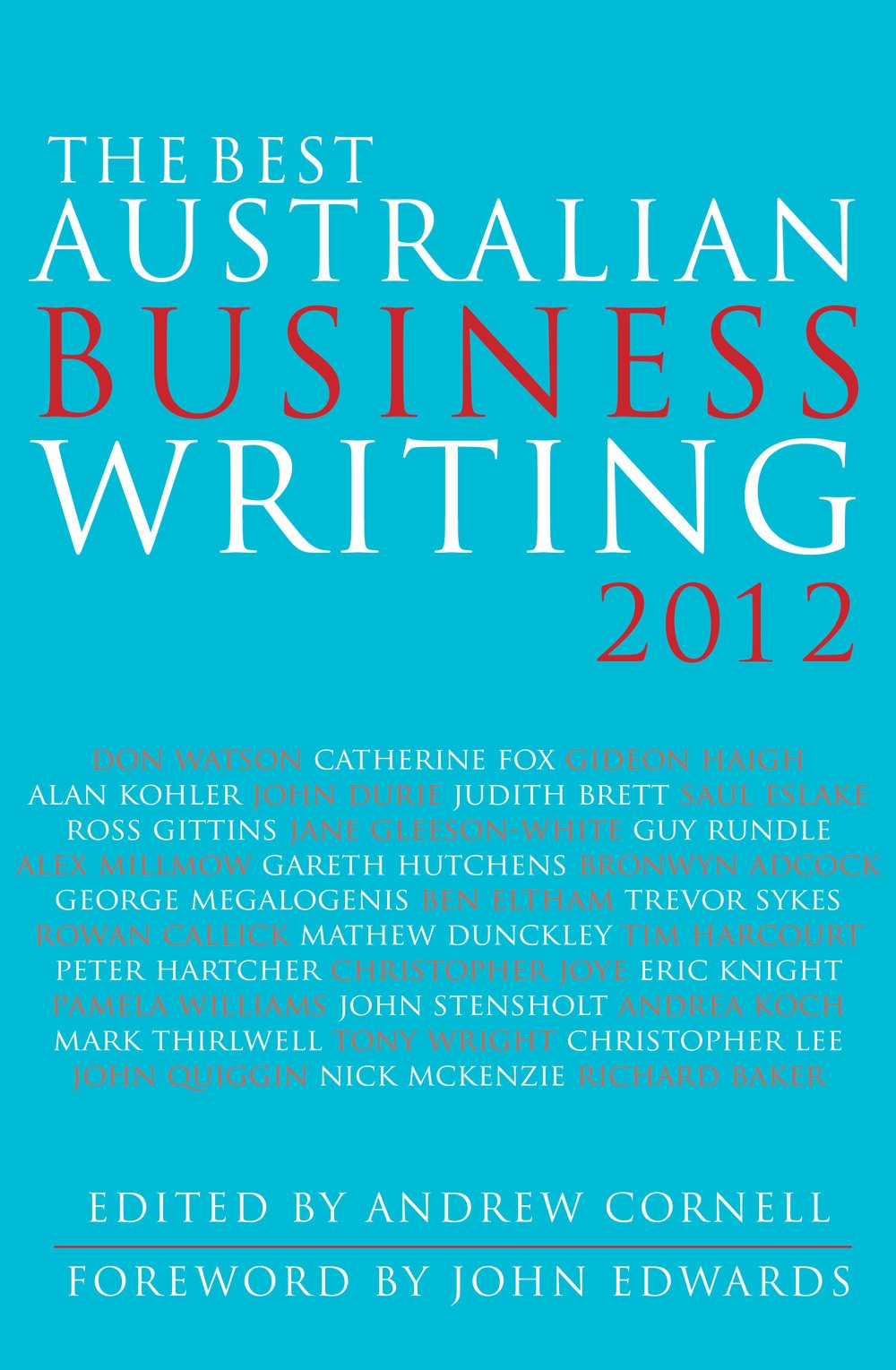

This is the foreword to The Best Australian Business Writing 2012, available now from NewSouth.