20 years after Indigenous AFL footballer Nicky Winmar stood up against racial abuse and made history, Adam Goodes experienced a grim redux.

It seemed like an awful parody. The AFL’s 2013 Indigenous round was not supposed to turn into another scandal around racist abuse. Not after a week celebrating the 20th anniversary of Nicky Winmar’s compelling gesture. Not with the most senior, celebrated Indigenous man currently playing AFL being vilified by a kid and denigrated by an AFL club president within three days. And yet here we somehow were, with Adam Goodes first called an ‘ape’ and then linked to King Kong.

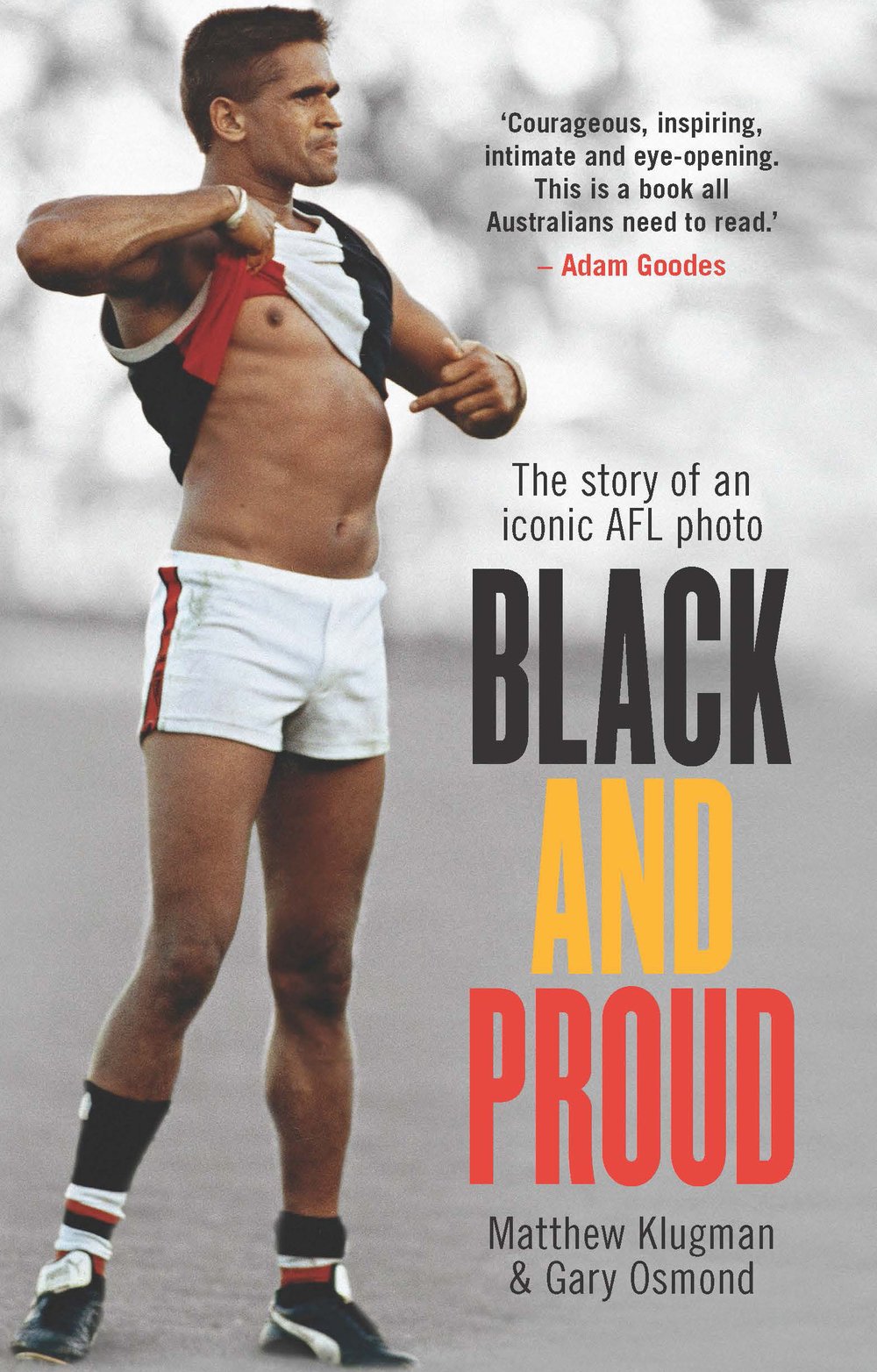

No footy picture taken in the last twenty years has spoken to racism as powerfully as the image of Winmar pointing in pride and defiance to the colour of his skin. But the image of Adam Goodes responding to the call of ‘ape’ came closest. It was late in the opening match of the 2013 Indigenous round. Adam Goodes, starring for Sydney against Collingwood, kicked the ball forward from the wing. His momentum took him along the boundary fence, then suddenly he turned around, drew the attention of a security guard, and pointed to the girl who had just unwittingly vilified him. Captured from behind by AFL photographer Andrew White, Goodes is statuesque in profile, as if he was intentionally embodying the latest campaign against racial vilification: ‘Racism. It stops with me’.

Speaking to the media the next morning, Goodes admitted that he was ‘gutted’. ‘How could that happen?’ he asked. ‘This week is a celebration of our people and our culture.’ Goodes had had the ‘privilege of meeting Nicky Winmar two days ago’ and felt that in pointing out this latest instance of racism he was following in Nicky’s footsteps. But the abuse had taken him back to high school where he was bullied with endless taunts along the lines of ‘monkey’ and ‘ape’ on account of his skin colour. Goodes hoped that the kid and everyone else would learn that these comments didn’t just hurt him, they hurt his brother, mother, family, and ‘all black people everywhere’. It was hundreds of years of painful history that made such ‘a simple name, a simple word, cut so deep’, and the Australian people needed to understand how hurtful it was.

Collingwood president Eddie McGuire seemed to understand all this. He’d been left ashen-faced by the incident and was the first person to go into the Sydney rooms after the game and apologise to Goodes. Yet less than a week later, McGuire suggested that Goodes should promote a new stage show of King Kong. Goodes was flabbergasted, McGuire ashamed. But initially at least, McGuire didn’t seem to understand just why his attempt at humour was so offensive and said he didn’t know where his reference to King Kong had come from.

The two instances provided a revealing insight into just what has and hasn’t changed in the 20 years since Winmar had made his famous gesture. The girl who vilified Goodes was promptly escorted by security out of the MCG. The actions might have been heavy-handed, but it was a clear sign that racist abuse by spectators was no longer tolerated. A year earlier, Collingwood player Dale Thomas had gone as far as pointing out a Collingwood barracker who was racially abusing his opponent, Joel Wilkinson, an act celebrated as symbolising the end of racism in Australian Rules football. Yet not only were moments of abuse continuing to occur, much of the public response to the denigration of Goodes was disturbing. Many people simply didn’t understand why he was so offended and advised him of the need to harden up and deal with such trivial insults.

The lesson unintentionally provided by former Collingwood president Allan McAlister had been forgotten – the public link between racist abuse and the history of damaging assumptions of Indigenous inferiority had been lost. And not for the first time. Indeed, what struck us in researching the history and impact of Nicky Winmar’s gesture is just how frequently key moments in the struggle for Indigenous rights featured on the front pages and then disappeared from public memory. Somehow there was no enduring story of Australia’s highly problematic race relations for these moments to become part of.

The photos of Winmar are an intriguing exception. Australian Rules football is the language of much of Australia. What happens on footy ovals at the elite level is likely to be remembered, debated and told over and over again. And Winmar’s stunning statement brought race into the heart of this conversation. The power of the image facilitated important change. But for the underlying causes of racism to be addressed, we need to begin remembering more than just Winmar’s gesture.

In the aftermath of Goodes’s vilification, Jason Mifsud, the AFL’s head of diversity, made a critical point. Unconscious biases and assumptions reveal themselves in moments of rage and attempts at humour. The enraged call of ‘ape’ and supposedly humorous joke about King Kong both pointed to the assumptions promulgated by the long-discredited science of race. Both were deeply offensive because they link back to a history of discrimination and violence that was justified by claims that Aboriginal peoples were lesser humans. Yet this history remains largely neglected outside of universities and Indigenous communities.

Not only do we need to know about Nicky Winmar’s gesture of pride and defiance, we also need to know more of the history of settlements like Pingelly and of the lives of people like Sir Doug Nicholls, and Charlie and Val McAdam. These are not only tales of discrimination, but also of resistance, power, pride and triumph. Until they are remembered, Australian Rules football, and Australian society more generally, will remain a site of unwitting, as well as witting, expressions of racism. It’s hard to think of a more compelling justification for the importance of history.

***

This is an extract from Black and Proud: The story of an iconic AFL photo by Matthew Klugman and Gary Osmond, which was published by NewSouth in November 2013. Black and Proud won the Multicultural NSW Award at the NSW Premier's Literary Awards 2015.