Nancy Underhill had plenty of good reasons to take on the monumental task of writing a new biography of Sidney Nolan. In this extract from her introduction to Sidney Nolan: A life, she explains her continued fascination with the man and his work.

Why another book about Sidney Nolan? That was my immediate response when NewSouth Publishing suggested I write one. In the UK, my art and publishing world friends had a single response: ‘Of course you must.’

Nolan remains a topic of interest for any evaluation of late-twentieth century British art. Yet despite Nolan basing himself in the UK from 1953 until his death in 1992, the main Nolan references, aside from commercial exhibition catalogues, remain the 1957 catalogue for his retrospective at London’s Whitechapel Gallery and the 1961 Thames & Hudson monograph Sidney Nolan. My friends were interested to know how Nolan’s carefully nurtured fame had affected reactions to his later works. Some also wondered what Australians thought of Nolan’s depictions of so-called ‘true Australia’.

In Australia, the public still tends to truncate Nolan’s life at July 1947, when he quit living with John and Sunday Reed at their home, Heide, outside Melbourne. Like Sunday, the public locks Nolan’s fame onto the group of Ned Kelly paintings he left with her. Once she gave them to the National Gallery of Australia, those paintings became her very public memorial to lost love, and supported the Reeds’ claim to have nurtured Nolan’s genius. He became simply the man who painted Kelly.

Nolan deserves a more broad-reaching critical biography, informed by art historical assessments. Questions and issues began to bubble in my mind. I had met Nolan several times. I had already researched the Reed Papers, held in the State Library of Victoria, and Nolan’s own archive, at his home, The Rodd, on the Welsh border. Finally, I knew or could arrange to meet his associates in Australia and the UK. On that basis, I agreed to undertake what has proved to be a very complex and intriguing journey.

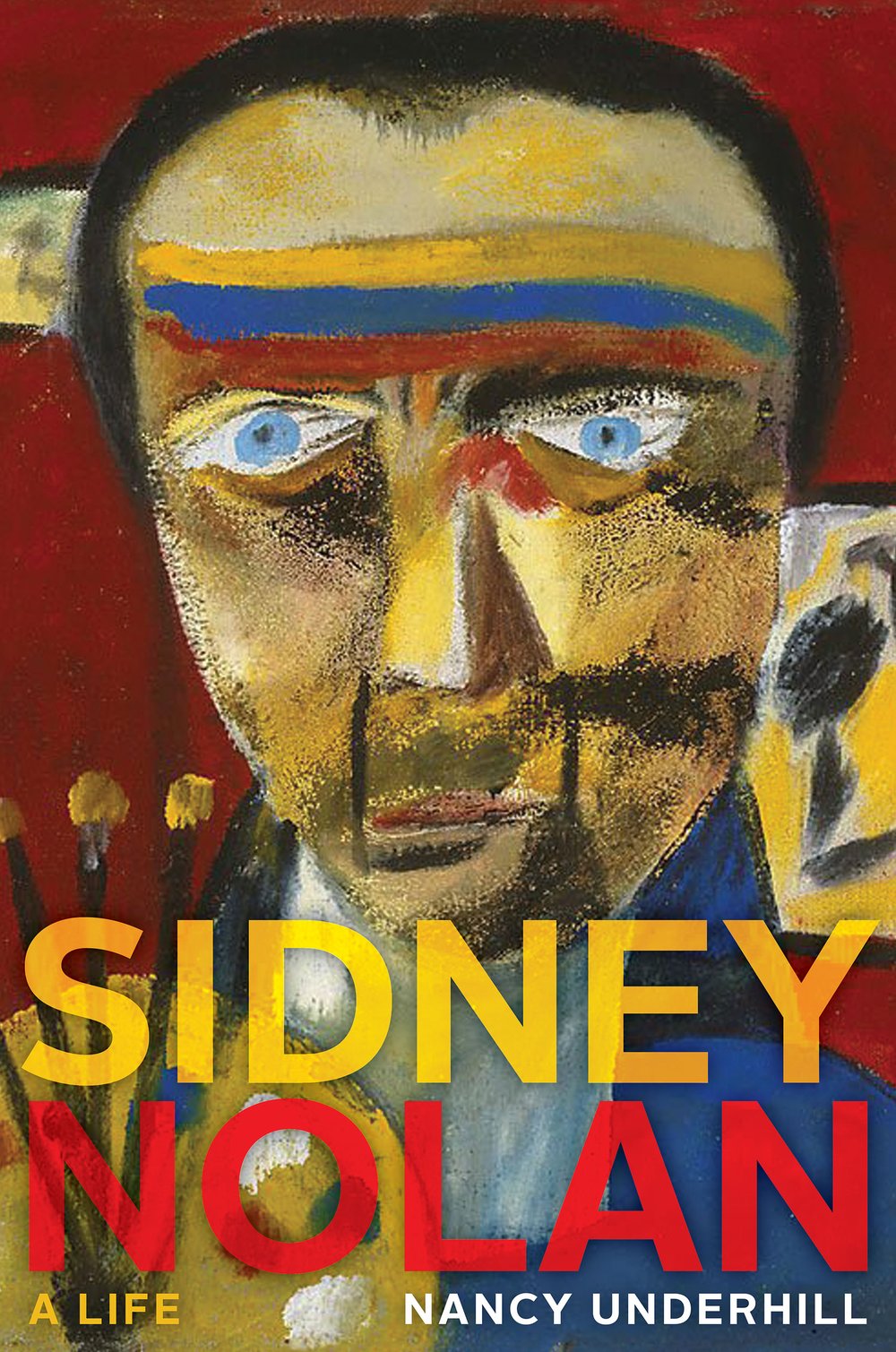

Sidney Nolan at the beach, 1940s, by Albert Tucker.

[Albert Tucker Photographic Collection, Heide Museum of Modern Art & State Library of Victoria]

I soon discovered how systematically Nolan controlled his own biography. In London, Bryan Robertson, Kenneth Clark and Colin MacInnes, who were instrumental in establishing Nolan’s reputation, took Nolan at his word and, worse, used his art to portray Australia as a vast land where everything was upside down and, to paraphrase MacInnes, frankly weird. Nolan airbrushed from his UK life story the Reeds, his training as a commercial artist and his interaction with other Australian artists.

On visits to Australia, somehow a reporter was often at the ready to convey Nolan’s desire to live there one day, and how the country recharged his batteries. Despite his substantial UK financial success and fame, Nolan appears to have had a genuine emotional bond with Australia, and he depended on sales there to bolster autobiographical film projects and his endless world travel. As always, however, it was Nolan’s call as to what got told. Having decided to tackle a biography using art historical evaluations, I determined to cross-check the extant Nolan material and rebalance Nolan’s Australian persona by fleshing out his international life and career. I was very lucky. Many of Nolan’s colleagues, studio assistants and friends in the UK, New York and Australia, who had not previously been interviewed, were willing to meet with me and in the process discover a great deal about their friend. Two things struck me about this group. They were high achievers in diplomacy, music, literature and finance, but few were in visual arts. The likes of Stephen Spender, Benjamin Britten and Kenneth Clark, who had been admired from afar by a young Nolan in Australia, became close friends in the UK—not something that often happens to a tram driver’s son from St Kilda. Equally fascinating was that despite admitting Nolan had a rogue, secretive facet to his personality, his colleagues all found him intellectually stimulating company. For those who owned any, his art was more a memento of a friendship than a trophy hanging on their wall. What greater compliment could an artist have?

Sidney Nolan: A life took me on a journey full of barbed wire but one I am pleased I agreed to undertake. Imagine missing seeing all that art, reading diaries and private letters, meeting incredibly interesting people and coming to better know an artist who still intrigues. My publishers were right: Nolan did deserve another sort of biography. He was an elusive and controversial man who became Australia’s best-known artist.

* * *

This is an edited extract from Nancy Underhill’s Sidney Nolan: A life, published by NewSouth in June 2015. For more background on the biography and Nolan, you can listen to Nancy Underhill’s conversation with Phillip Adams on ABC Radio National here and here.