On Saturday 3 May 1975, twelve families signed a letter to the Australian government. The men and women introduced themselves as librarians, teachers, police officers and nurses from Vietnam, and with their sixteen children they were sheltered in Singaporean waters, aboard a 24-metre fishing boat. Just days earlier the families had fled Saigon along with thousands of other residents, when advancing North Vietnamese forces attacked the outskirts of the city and Saigon ‘fell’ on 29 April 1975, marking the end of the United States’ war in Vietnam. In the letter the families explained how they had sailed under gunfire from the river bank and out into the open sea ‘to save our lives’. ‘Some of the fleeing boats’, they wrote, ‘were hit by the shore fire and burnt but we were probably lucky’. And they added that once they could take aboard provisions, they would sail south in the ‘strong belief’ that the government and people of Australia ‘will accept us with pity in the country as refugees’. Together the families pledged: ‘We will do our best for the rest of our lives to contribute to the Commonwealth of the Royal Australia’.

We do not know the fate of these families. Their letter was strategically cited at a news conference, held that Saturday by Singapore’s Ministry of Defence to publicise the challenge Singapore was suddenly facing, along with other letters addressed to the United States Embassy and the Singaporean government. These notes had been penned by just a few of the more than 6500 refugees who reached Singapore that week aboard wooden fishing boats, large trawlers and tankers. Many people arrived with nothing. Singaporean welfare societies collected donations of food and clothing, and refugees with shrapnel wounds were taken to hospital. Thousands more Vietnamese refugees had escaped by boat to Thailand or out into open seas, and were reported adrift on barges or fishing boats, hungry and exhausted, desperate for fresh water and a tow to land.

In Canberra, Deputy Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Geoffrey Yeend, was paying close attention to news of the arrivals in Singapore harbour. Australia’s Labor government, led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, was not yet prepared to commit to resettling any of the refugees. On 8 May Yeend advised the Department of Foreign Affairs that in the meantime his ‘chief concern’ was avoiding ‘unfavourable publicity’ for the government.

That night the phone rang, and Yeend was told by Kenneth Rogers from Foreign Affairs that Singaporean authorities were helping the Vietnamese refugees to press on, and were handing out navigational charts for Australia and the Philippines. Foreign Affairs sent cables to missions in Geneva, New York and Washington, appealing for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to pressure Singapore to ‘hold the ships’ until ‘arrangements could be made’. As yet the Australians were not sure what these arrangements might be.

The next morning Yeend gathered with the Deputy Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs JR Rowland and Acting Prime Minister Dr Jim Cairns to talk over the idea that if some people did leave Singapore and head south, the navy would need to meet and escort them ‘to the appropriate reception points’. Yeend returned to his office to write up his notes. A highly regarded public servant, described as calm and unflappable, Yeend would later head Prime Minister and Cabinet under the Liberal/National Coalition government led by Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. On this morning, Yeend put into words an idea that would come to occupy successive Australian governments: ‘[…] if ships were sailing towards Australia we would need to look something better than helpless’.

In using this expression Yeend was referring to the logistics of managing and aiding vulnerable people, as Singaporean authorities and charities were doing at that very moment, but his choice of words also reflected a belief that government must control (and appear to control) entry to Australia. As a white, settler society on the edge of Asia, control of entry was a founding principle at Australia’s federation in 1901. It is a ‘pillar’ of Australian immigration policy, according to leading immigration scholar James Jupp, and the nation’s population has been ‘planned and engineered to a greater extent than is true for almost anywhere else’.

Australia is a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol (the Refugee Convention), which are the chief instruments under which states have made commitments to one another ‘in good faith’ to protect people who are fleeing persecution. Yet the Australian government views the arrival of asylum seekers by boat, without valid visas, as challenging control of entry. Further, these boats attract media interest and public disquiet that is disproportionate to their numbers. Peter Mares has described this as the product of a society that is ‘hostile to its foundations’ as ‘one of the world’s true immigrant nations’. In his book, Borderline: Australia’s treatment of refugees and asylum seekers, Mares drew a parallel between the response to boat arrivals in contemporary Australia and an historic sense of geographic vulnerability within the national psyche:

‘There is a deeply held, yet irrational anxiety that Australia is perpetually in danger of being overrun; that our sovereignty is brittle and our borders are weak. It is as though this continent were a rickety lifeboat, and all the world’s oppressed and poor are desperately swimming towards us, threatening to drag us under.’

By 11 May 1975, many of the refugees in Singapore harbour had accepted charts, fuel and provisions, and had departed in the hope of sailing to the United States’ territory of Guam thousands of kilometres to the north-east or, somewhat closer, Subic Bay in the Philippines. At an interdepartmental meeting a week later, on 19 May 1975, staff from Labor and Immigration, Foreign Affairs, Prime Minister and Cabinet, and seven other departments worked through possible courses of action should some of the refugees sail to Australia. They noted that if a boat arrived it would likely attract media attention, and believed that if those on board were allowed to land the precedent would not go unnoticed in countries to Australia’s north, whether in relation to an ongoing exodus of Vietnamese or future political unrest ‘in countries to our immediate north’.

The departments noted the need to consider Australia’s obligations under the Refugee Convention toward asylum seekers arriving in Australia. They debated whether a boat could be prevented from entering Australia’s territorial waters in the first place, perhaps re-fuelled and directed elsewhere, although recognised ‘it would be very difficult to insist on the departure of a boat […] in view of the distance and difficulty involved in reaching any alternative country of sanctuary’. They then proposed that a boat be allowed to land and passengers taken into custody, and based on the briefing paper they prepared, Prime Minister Whitlam chose the option of custody. But the boats did not arrive on his government’s watch.

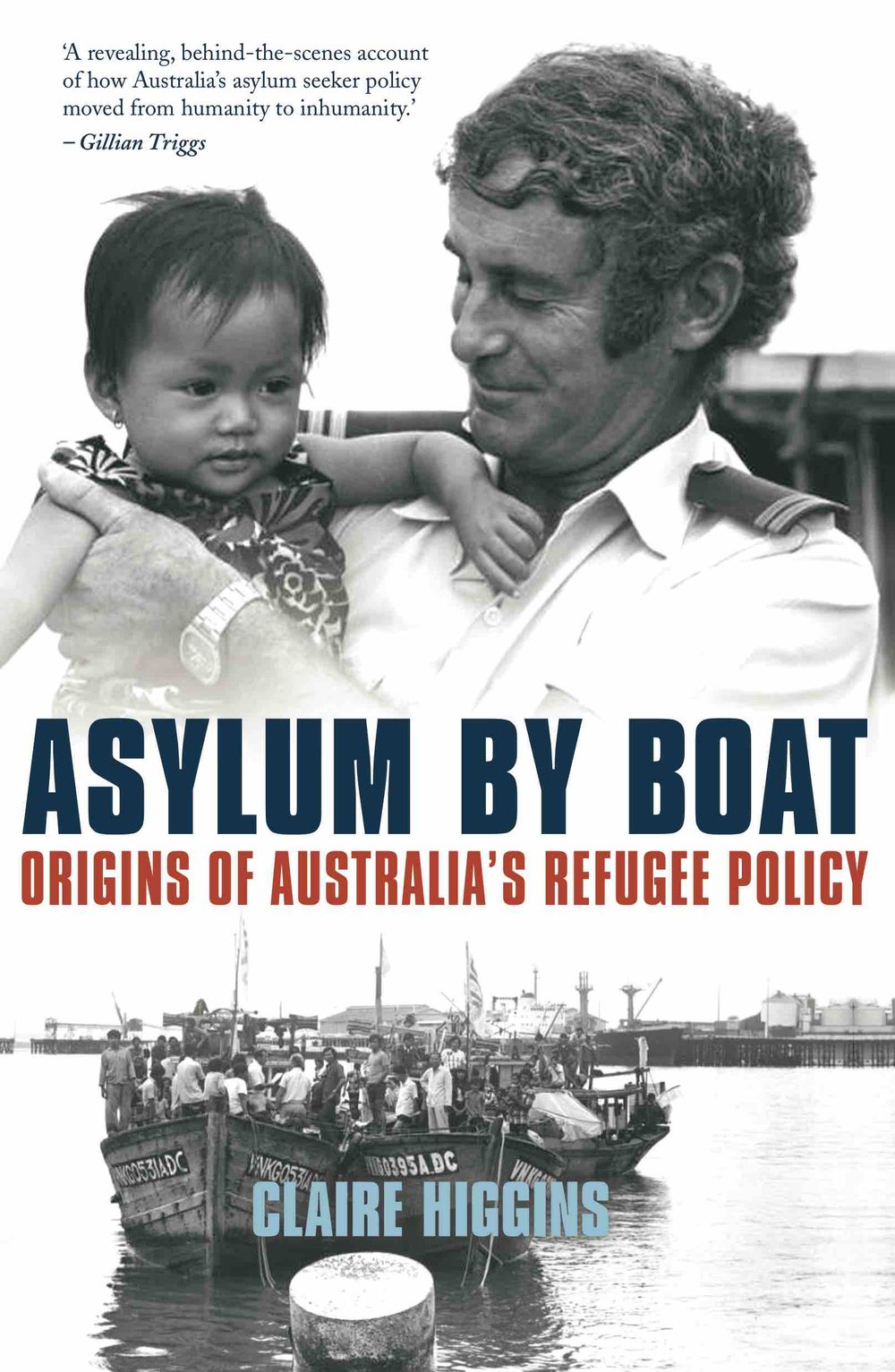

By the time five young Vietnamese refugees steered their way into Darwin harbour in April 1976, the Fraser government was in office. Just over 2000 more refugees would arrive by boat between 1976 and 1981, during which time more than a million refugees would flee Indochina, and the Fraser government would work through the same issues its predecessor did at that interdepartmental meeting in May 1975. How did the Fraser government attempt to control the maritime arrival of asylum seekers, and to look, in Yeend’s words, ‘better than helpless’? That process will be the main focus of this book.

Claire Higgin’s book Asylum by Boat is published by NewSouth in September 2017.