POLITICS / AUSTRALIAN HISTORY

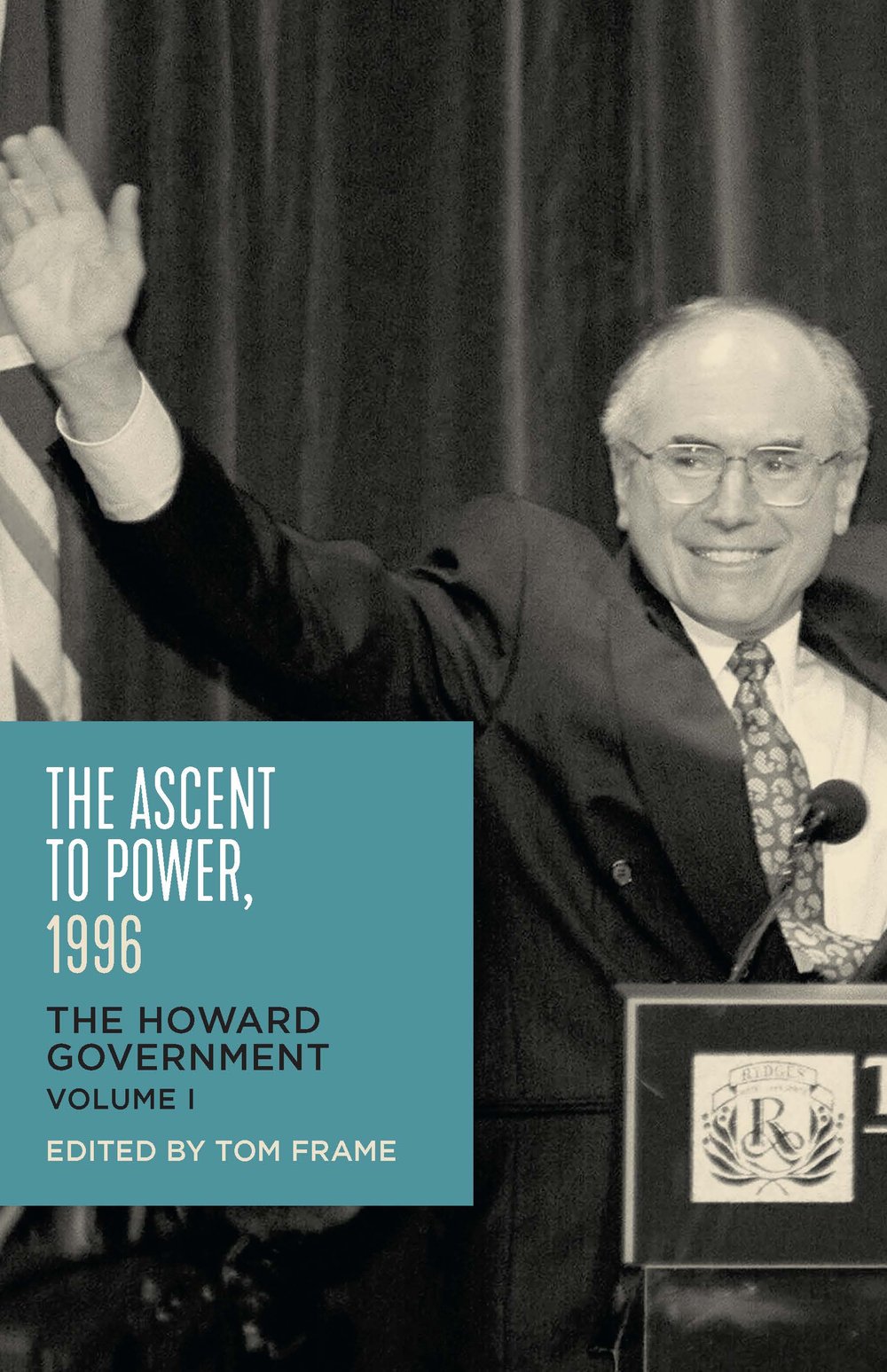

Extract from Paul Kelly’s chapter (‘The foundational year’) in The Ascent to Power, 1996 by Tom Frame (Ed.)

The year 1996 was a turning point in Australian politics. It saw the Coalition returned to office after the longest period of Labor rule at the national level. There was nothing inevitable about the Howard Government. Indeed, there was nothing inevitable about either the 1996 result or what might be called the ‘Howard era’ from 1996 to 2007.

It is too easy in retrospect to assume the certainty of such outcomes. The reality is different. If you had suggested in early 1996 to a round table of astute observers that John Howard would win four elections and become the second-longest serving prime minister to Sir Robert Menzies you would have been dismissed as delusional. It is true that people expected Howard to win the 1996 poll but there was no certainty of view about the likely extent of such success. Indeed, there was pre-election apprehension within the Coalition that Paul Keating might spring yet another political surprise given his 1993 victory against the trend. There was no expectation in early 1996 that Howard would enjoy the sort of long and successful prime ministership that followed. This highlights the first challenge for the Howard project – to explain the Howard era, to explain how and why it happened rather than pretend it was ordained or inevitable.

In 1996 the Coalition had been in opposition for 13 long years. Many of these years had been marked by Liberal Party division and ineptitude. In 1993 the Liberals had lost what many called the ‘unlosable’ election when Keating defeated John Hewson after the early 1990s recession when unemployment had exceeded 11 per cent. Not only was there no certainty in early 1996 that the Liberals, if they won, could constitute a meaningful period of government but there was private apprehension in the party about such prospects. A lot of psychological harm had been done during the bitter years of opposition.

The year 1996 is pivotal not only because Howard won but because much of the foundation for the Howard era was laid in this first year of office. It is true there were more dramatic and eventful years in Howard’s prime ministership. But a strong case can be made that 1996 was the most important year. For this reason I have called it the foundational year. From the start, two of the most dominant and practical themes of the Howard era were apparent – his commitment to economic reform to improve living standards and his belief in a cultural traditionalism to confront the values and political correctness of the Labor period. Both these ideas, economic and cultural, would challenge the Keating legacy. They became central to an intense and evolving debate about what Howard stood for. But with the passage of time they left no doubt that Howardism was grounded in ideas and values that reflected a clear vision about the nation.

That vision was not revealed in any Mount Sinai type moment of grand design but emerged in policy decisions and rhetorical stances in response to events. Howard was both a pragmatist and a conviction politician and the record suggests he struck a more successful balance between the two than many prime ministers. The most vital part of his political foundation was leadership certainty. The extraordinary prime ministerial instability in the decade following Howard’s 2007 defeat has merely highlighted this point. In this period there was a change of prime minister effected by the party room in each of the following three parliaments: Kevin Rudd replaced by Julia Gillard in 2010; Gillard replaced by Rudd in 2013; and Tony Abbott replaced by Malcolm Turnbull in 2015. The abrupt break from the Howard era was conspicuous.

The leadership transition of 1995 involved three men – Howard, the incoming leader and future prime minister; Peter Costello as deputy who supported the transition and became the treasurer; and, Alexander Downer, the resigning leader who became the foreign minister. The Howard–Costello–Downer compact was a plan to deliver better Liberal leadership and win the election. But it did far more. It delivered the most prolonged Liberal governing success since the Menzian age. It brought together New South Wales and Victoria, conservative and moderate opinion. It was driven by a sense of desperation, the fear that the Liberal Party might lose a sixth successive election. The settlement not only produced a long period of stability but saw Howard, Costello and Downer in their respective positions for the entire 11 years. This was basic to the character of the government. Despite subsequent Howard–Costello leadership tensions, this settlement underwrote the stability of most of the Howard era.

Ultimately, the key to success lay in the character and judgment of the recalled leader. For Howard, the stars came into alignment. Labor had outlived its time in office after five terms; Howard was tougher and more seasoned than in his first appearance as leader; and he had learnt some decisive lessons. The single most important lesson was to lead and govern for the entire party, not one wing of it. Howard was no longer a spokesman for the Liberal ‘drys’; he was a spokesman for the Liberal Party as a whole. From his return he operated on the principle of the Liberals as a ‘broad church’ and steadily fashioned an inclusive philosophy of the party as embodying two great traditions, liberal and conservative. This was both a unifying notion and an expansive notion that aspired to broaden the party’s appeal.

Tom Frame’s book The Ascent to Power, 1996 is published by NewSouth in November 2017.